One of the ironies of the current debate about how Australia should adjust its military strategy in light of the changing great-power balance in the Indo-Pacific is that many of the participants—regardless of their views on the future of US military power—make similar recommendations, namely, that Australia should seek greater defence self-reliance.

This would be achieved by capability solutions based largely on ‘more of the same’. That is, to meet an increasingly uncertain strategic environment, our future force structure should be built around more of the things we already have, or are getting, such as F-35A joint strike fighters and submarines (even if some advocate different submarines from the ones we’ll eventually get under the current plan).

So it’s important to understand those systems and their limitations to see what additional capability more of them would provide. Since Australia and its region are geographically far-flung, and we have only a small number of military assets, we’ll focus on their ability to maintain a presence over large distances. The key question is, to what extent do the capabilities the Australian Defence Force is acquiring enable Australia to project power and what would further enhance that power projection?

We’ll start with the F-35A. Defence is in the process of acquiring 72, with potentially some more down the track. The F-35A is now a very capable aircraft, but it still faces the old problem that, no matter how good a military platform is, it can’t be in two places at once. And due to the inherent limitations of fighter aircraft, there are a lot of places they can’t be at any time.

Most Australians’ experience of aviation involves getting on a passenger jet in a major Australian airport and getting off on another continent, say in Los Angeles, Dubai or Tokyo. But those kinds of ranges are vastly greater than what modern fighter aircraft can achieve. This is a characteristic of all fighters; the F-35A has pretty good range in comparison to its peers.

The air force’s website lists the F-35A range at 2,200 kilometres, which is how far it can fly in a straight line. That doesn’t get the aircraft from the RAAF’s main fighter base at Williamtown in NSW to Perth (3,363 km) or Darwin (3,108 km). But since you want the pilot and aircraft to get home from the mission, its combat radius of 1,093 km is a more meaningful number than range.

There are three radii that are useful to consider in the context of the F-35A: they are (roughly) 500 km, 1,000 km and 1,500 km. The one that is most appropriate depends on the mission and how many resources Defence is able to apply to achieve it.

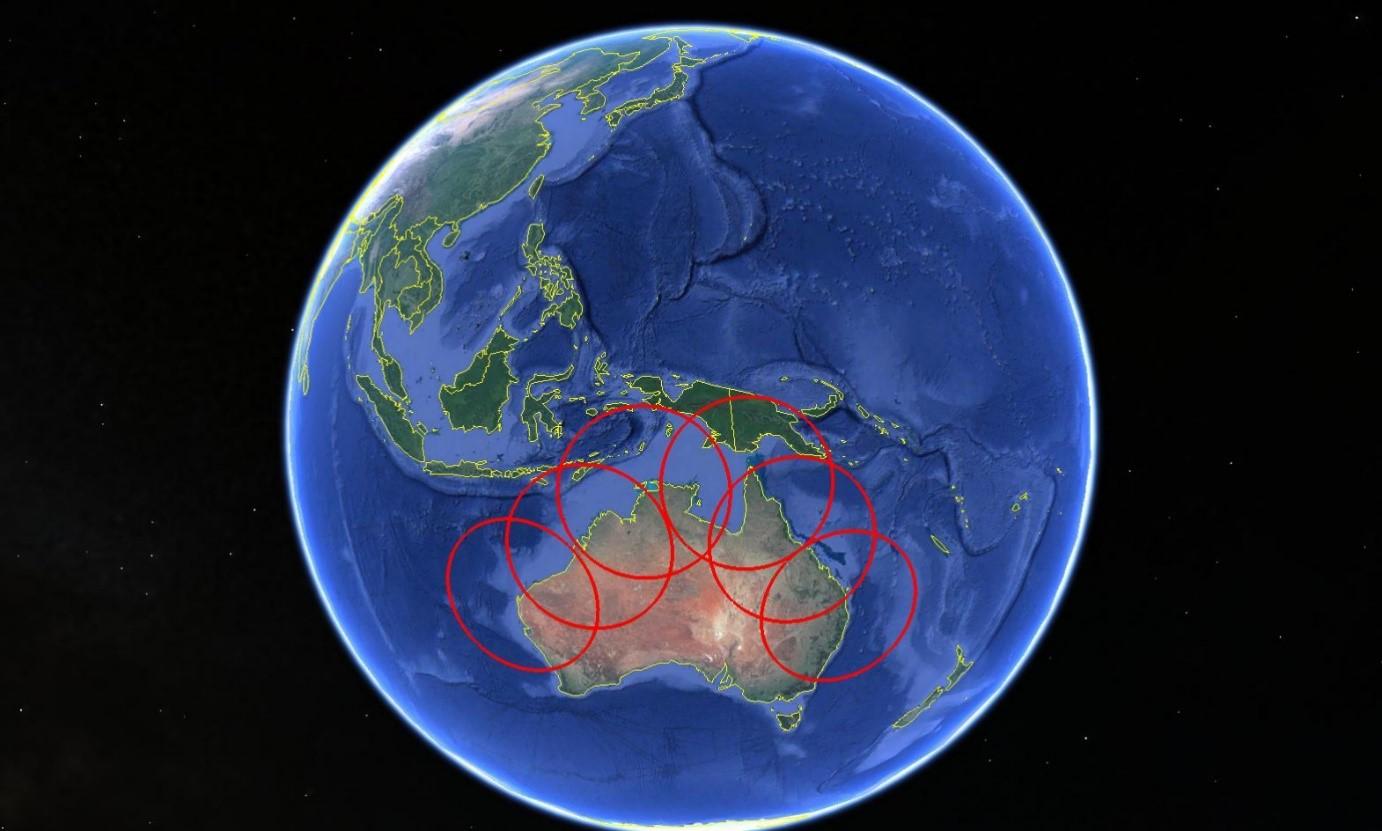

The ‘owner’s manual’ radius of the F-35A is essentially 1,000 km with a little margin built in to take into account real-world factors. What does that look like in the vast distances of the Indo-Pacific or the blue continent of the South Pacific? The map below is based on one developed by my ASPI colleague Malcolm Davis. The red rings represent the F-35A’s combat radius operating from the six mainland airbases in Australia’s north: Darwin, Townsville, Amberley, the bare bases at Curtin and Learmonth in Western Australia, and Scherger on Queensland’s Cape York Peninsula.

Figure 1: 1,000-kilometre combat radius from northern Australian bases

So, 1,000 km doesn’t project very far out into the vast distances of the Indo-Pacific. It doesn’t even get very far out into our South Pacific backyard. At least from our northern bases we can cover our immediate approaches. However, the RAAF couldn’t operate all those rings simultaneously with the three squadrons on order (and a fourth made up of the Super Hornet, or whatever replaces it).

But 1,000 km doesn’t include fuel to stay on station, so while it may be helpful for understanding range for a strike mission (fly out, launch ordnance, fly home), it’s not a useful number for missions where the aircraft have to loiter—for example, protecting a deployed maritime or amphibious task force, or providing close air support to land forces. The more time on station, the less range.

Moreover 1,000 km isn’t necessarily a representative number for air-to-air combat in which fuel consumption increases exponentially as the aircraft accelerates to combat speed or uses afterburners. In short, an F-35A that flies out 1,000 km and fights enemy aircraft probably isn’t going to make it home, so a 500 km combat radius might be more accurate when it comes to an air defence role or one that requires some time on station.

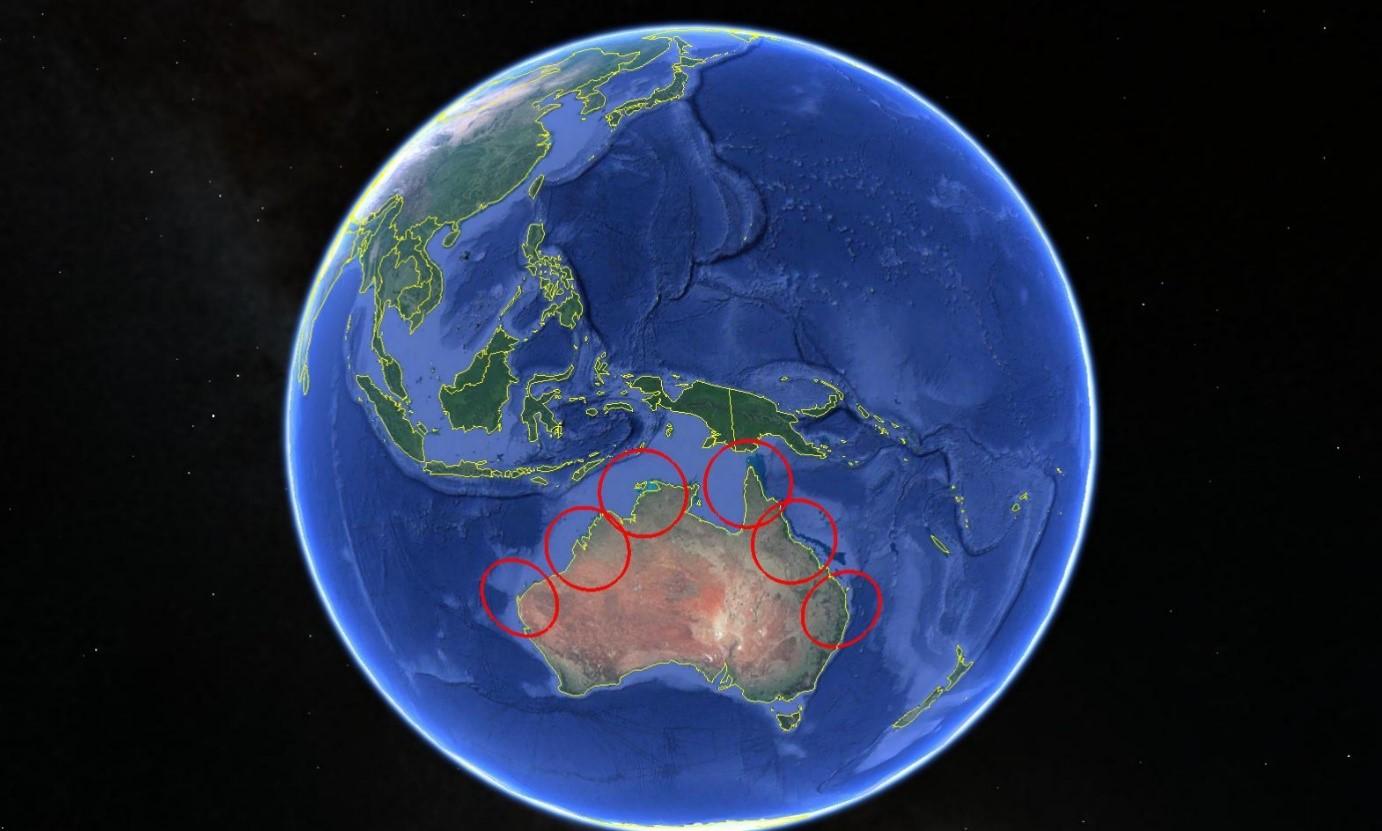

Figure 2: 500-kilometre combat radius from northern Australian bases

That makes a big difference. There are now gaps between the red rings, even if we could operate in each of those rings simultaneously. And the longer you want the aircraft to loiter on station, the smaller that radius becomes.

Moreover, it’s difficult for the F-35A to sustain a continuous presence over any land mass outside of the continent, which means a maritime task force could only be protected if it was operating very close to the Australian mainland, or, in the case of an amphibious task force, if it was seeking to deploy its land component actually on Australian soil.

Of course, this analysis doesn’t take air-to-air refuelling into account. In part 2, I’ll examine how tankers change the picture.