Imagine this. You wake up in 2022 to discover that the Australian financial system is in crisis. Digital land titles have been irreversibly altered, and it’s impossible for people and companies to prove that they own their assets. The essential underpinning of Australia’s multitrillion-dollar housing market—ownership—is thrown into question. The stock market goes into freefall as confidence in the financial sector evaporates. Banks cease all property lending and stop any business lending that has property as collateral. The real estate market, insurance market and ancillary industries come to a halt. The economy begins to lurch.

At the same time, a judge’s clerk notices an error in an online reference version of an act of parliament. It quickly emerges that a foreign actor has cleverly tampered with the text, but it’s unclear what other parts of the legislation have been changed or whether other laws have been altered. The whole court system is shut down as the entire legal code is checked against hardcopy and other records and digital forensics continue.

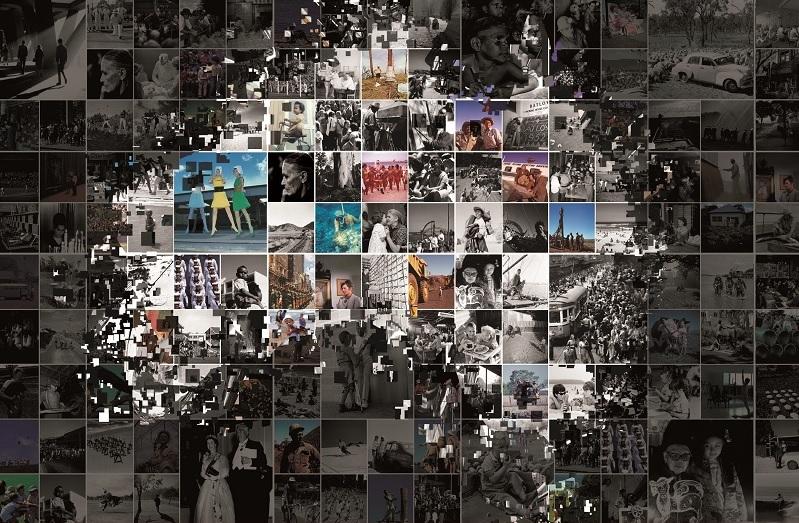

Meanwhile, a ransomware attack has locked up the digital archives of Australia’s major media organisations and parallel archival institutions. Over 200 years of stories about the nation are suddenly inaccessible and potentially lost.

As the Australian public and media are demanding answers, the government is struggling to deal with the crisis. Paper copies of many key documents simply don’t exist.

National identity assets are the evidence of who we are as a nation—from our electronic land titles and biometric immigration data, to the outcomes of our courts and electoral processes and the digital images, stories and national conversations we’re having right now.

Increasingly, our national footprint and interactions are digital only, including both digitally born and digitalised material. The electronic repository is quickly becoming the primary source of truth—the legal and historical evidence we rely on now and into the future.

Keeping national identity assets safe and accessible is vital not only for chronicling Australia’s past, but for supporting government transparency and accountability, the rights and entitlements of all Australians, and our engagement with the rest of the world.

In my report for ASPI’s International Cyber Policy Centre, Identity of a nation: protecting the digital evidence of who we are, released today, I argue that our national identity assets are a prime and obvious target for adversaries looking to destabilise and corrode public trust in Australia.

According to the Australian Cyber Security Centre, 47,000 cyber incidents occurred in Australia in 2016–17, a 15% increase on the previous year. Both state and non-state adversaries have the capability to disrupt, distort and expropriate national identity data. So far, they haven’t targeted our national identity assets—but that could change, at any time.

Many national data assets are held electronically by government agencies, archives, records agencies, libraries and other recordkeeping institutions. Because we haven’t anticipated sophisticated cyberattacks against the organisations holding these assets, and because the data is generally undervalued, the protections in place are inadequate.

In addition to the risk of data loss, there’s also a risk of a loss of trust in the organisations and governments that hold national identity assets.

National and state government archives and other record-holding institutions play the role of ‘impartial witnesses’, identifying and storing this information and holding the government to account under the rule of law and in the ‘court’ of history. We need to trust that these impartial witnesses can identify, keep and preserve this evidence.

If we aren’t vigilant, we run the risk that adversaries could destroy or manipulate our national identity assets, compromising the digital pillars of our society and culture.

States such as Russia have demonstrated their intention to disrupt and undermine Western democracies, and obvious future targets for such attacks are national identity assets that are poorly protected and offer high-impact results if disrupted, corrupted or destroyed.

With more than 30 countries known to possess offensive cyber capabilities, and cyber capabilities being in reach of non-state actors from individuals to cybercrime organisations, the number of potential adversaries able to target our national identity assets is significant and increasing.

The Australian government’s Critical Infrastructure Centre and Australian Cyber Security Centre should address gaps in our national infrastructure and information security by including national identity assets in our critical infrastructure framework and closely aligning digital preservation and information security.

We also need to develop ways of better identifying and valuing national identity digital assets and to give more attention to information governance. Australian governments—state and federal—need to ensure that our critical government-held national identity assets are protected and institutions charged with their care are adequately funded to do so.

Until these issues are addressed, the increasing vulnerability, invisibility and potential loss of the digital evidence of who we are as a nation remains a sleeping, but urgent, national security issue.