For a glimpse into Australia’s future in a rapidly changing climate, have a look at Queensland, our most hazard-prone state.

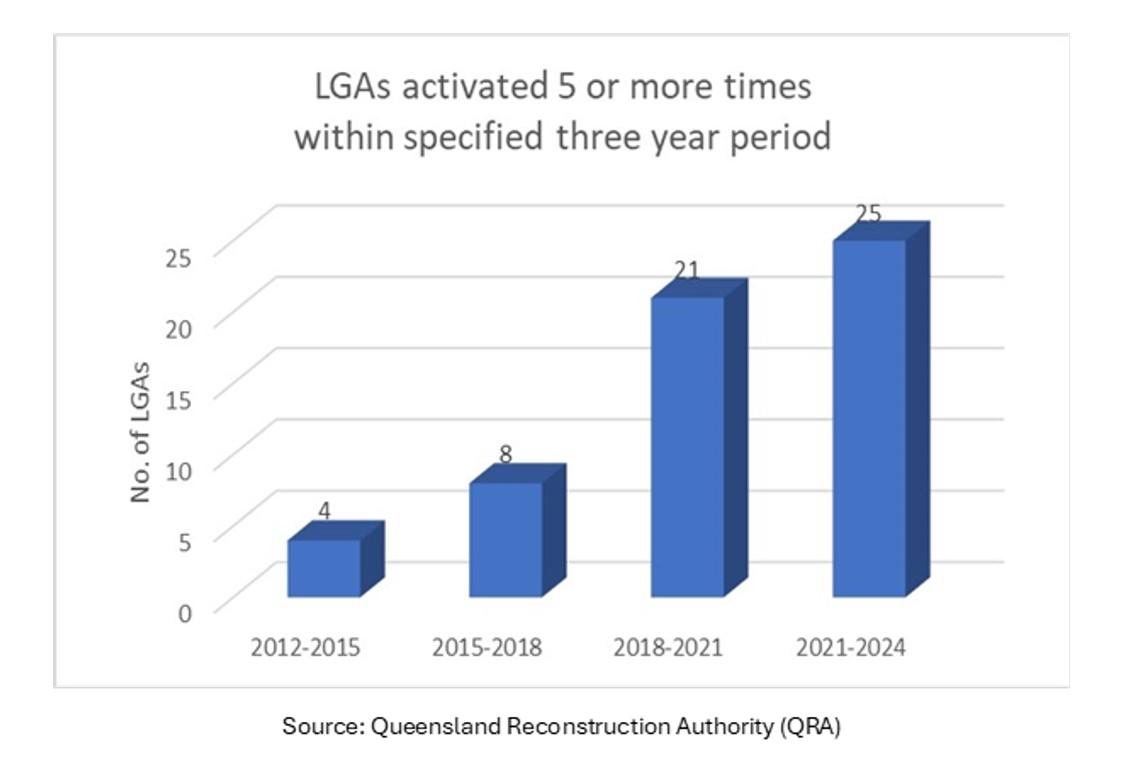

Recent government data shows that in the past three years, 60 of the state’s 77 local government areas (LGAs) have suffered three or more major climate-related disasters. In the same period, almost one-third of them have endured five or more disasters, a massive increase from a decade ago (chart below).

It would be comforting to be able to attribute this increase solely to ‘natural’ extreme El Niño or La Niña weather patterns, but climate change is likely amplifying both phenomena and increasing their frequency.

Alarm bells should be sounding at the prospect of this trend continuing and spreading across all of Australia. But research has shown there can be a ‘boiling frog’ effect on perceptions of climate impacts. In Australia, the impacts are manifested in events with which we are historically familiar—droughts, floods and fires.

The public’s reference point for ‘normal conditions’ is based on the weather experienced between two and eight years ago. And they are less likely to regard climate events as extreme if they have been previously exposed to them either directly or through media reports.

Climate change may be becoming the ‘new normal’ in all the wrong ways.

This means that all our existing emergency management planning and investments must be reality-checked against this rapidly emerging environment. We need to identify which of our current assumptions and programs will continue to be fit-for-purpose and identify innovative responses that match the scale of the change that is already underway and accelerating.

We currently spend far more on responding to, and recovering from, disasters, than on reducing future disaster and climate risk. We need to invest much more in the latter.

That begins with having a clear-eyed view of the challenge before us. Australia’s emergency response and disaster management processes and procedures are based on our historical experience of hazards and disasters. But history is no longer reliable. Like never before, the fire ‘season’ is expanding rapidly, cyclones are becoming more powerful and destructive and may be tracking further south, intense rainfall is shattering historical records and ‘weather whiplash’—wild swings between many extremes—is accelerating the danger and undermining community resilience.

This should not be surprising. The climate is now the warmest it has been in at least the last 100,000 years. To put that figure into context, the Great Pyramids were constructed about 4,000 years ago and Neanderthals died out about 40,000 years ago. We are clearly entering uncharted waters.

In 2011 the National Strategy for Disaster Resilience report stated that ‘it is uncommon for a disaster to be so large that it is beyond the capacity of a state or territory government to deal with it effectively’. This statement is rapidly becoming outdated. The fundamental reference point for our emergency planning must now become the extent to which we are reducing the risks of intensifying, increasingly national-scale disasters with rapidly diminishing time for communities to recover between events.

This will require addressing a profoundly separate set of strategic challenges, beginning immediately: How do we provide relief to exhausted emergency services personnel and volunteer emergency responders in an environment of, intensifying, back-to-back disasters? Will we be able to maintain the current level of response without a massive increase in personnel? How will governments meet the growing need for mental health support in communities buffeted by multiple, consecutive disasters? Given the existing shortage of skilled trades people, where will we find the tradies to rebuild homes and other infrastructure in this emerging era of disasters?

Australia’s largest insurer, IAG, estimated in 2016 that 28% of our GDP and 25% of Australians are in areas with high to extreme risk of flood and about 11% of GDP and 10% of people are in places with high and extreme risk of bushfire. These numbers are certainly much larger today, due to population growth and development, and because climate change is expanding the areas at risk.

Major insurers have recently begun increasing the costs of policies and withdrawing from markets where climate change is accelerating the risk of extreme hazards. Given the scale of our economic exposure suggested by IAG, if insurance becomes unavailable or unaffordable, the government will need to step in at enormous cost.

One response is to avoid building in these hazard zones. In the wake of recent record-setting floods, the federal government is supporting NSW and Queensland’s implementation of the largest home buy-back scheme in Australia’s history, to encourage owners to re-locate homes away from extreme flood risk. But these innovative and useful measures are extremely expensive, and it is unlikely that we can afford to regularly repeat and expand them.

Australia has the potential to become one of the world’s most climate and disaster resilient countries in the world. We cannot avoid our high exposure to existing climate hazards, but we can reduce our vulnerability by making better choices about where we live, how we build our infrastructure, which technologies we invest in, by strengthening social capital in our communities and—fundamentally—by accelerating our transition from fossil fuels to renewables and advocating for other countries to do the same. Queensland’s experience with disasters suggest we need to move in these directions much faster than we realise.