Australia should recognise Somaliland, a territory that is claimed by Somalia but has asserted its independence since 1991.

No country recognises Somaliland as independent, but if Australia led in doing so it could reinforce its commitment to democratic principles, bolster its influence in the Indo-Pacific region and counter Chinese expansion. It could also secure opportunities for Australian businesses in Somaliland, Ethiopia and beyond.

Failing to recognise Somaliland would encourage developments that could only be negative for Australia. If Somaliland remains a diplomatic and strategic vacuum, Houthis, terrorist organisations, China and other authoritarian regimes will eventually move in.

Between 1827 and 1884, Britain signed treaties with various clans and established Somaliland as a British protectorate. On 26 June 1960, Somaliland gained independence from Britain but four days later started a process of voluntary union with Somalia to form the Somali Republic. However, the act of union was never formally ratified through a legal process and was rejected by Somalilanders in a referendum in 1961.

In 1991, Somaliland reasserted its sovereignty. After an impressive locally funded state-building process, it has operated as a sovereign state for more than 30 years without formal international recognition. Somaliland’s story is one of resilience and stability, contrasting sharply with the turmoil characterising Somalia. Somaliland’s consistent peaceful democratic governance over the past two decades, though imperfect, makes it a role model for the global south. It estimates its population at about 5.9 million.

Like Lithuania, Somaliland hosts a de facto Taiwanese embassy called the ‘Taiwanese Representative Office’, not the usual ‘Taipei Representative Office’. And, like Lithuania, Somaliland has been pressured by China to close the office. Chinese attempts at influencing Somaliland are reminiscent of activity in the Solomon Islands. Australian recognition of Somaliland would help counter this and head off the risk of China strengthening its diplomatic position in the Horn of Africa.

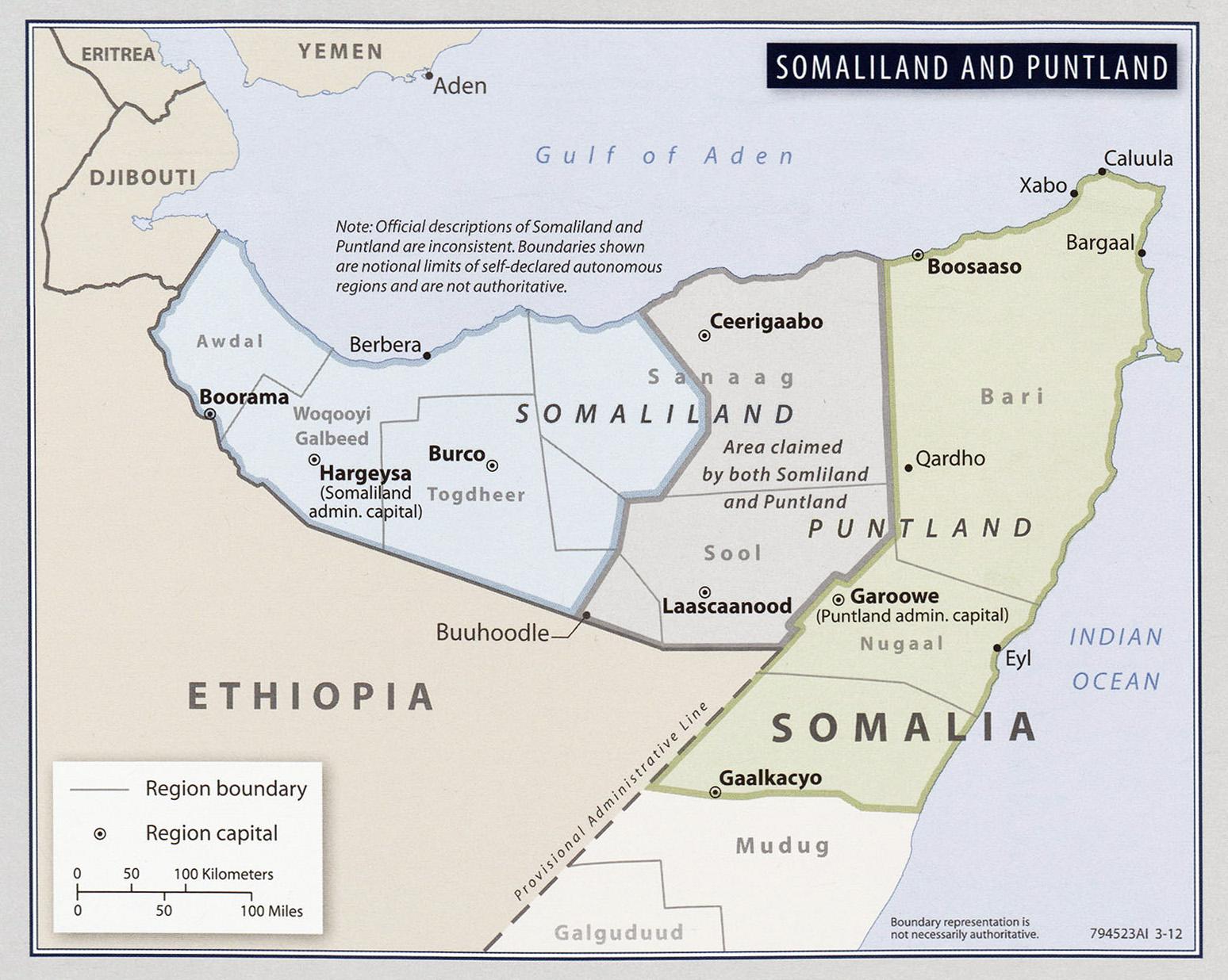

Despite being unrecognised, Somaliland has forged close relations with Britain, the United Arab Emirates, Kenya and Taiwan, maintaining a firm stance against China’s Belt-and-Road initiative. Recently, Somaliland has been more active in seeking recognition. US Congressional staff committees visited Somaliland in 2021 and 2024. Meanwhile, the US National Defense Authorization Act 2023 explores opportunities for increased collaboration with Somaliland in the Horn of Africa, Gulf of Aden and Indo-Pacific region. In the British parliament, the issue of Somaliland’s recognition has been raised several times in 2024, most recently with Defence Secretary Grant Shapps.

In January, Ethiopia and Somaliland signed a historic memorandum of understanding that, despite its rejection by Somalia, continues to progress. This agreement involves granting Ethiopia sea access in return for recognising Somaliland’s sovereignty, indicating a strategic alignment that extends beyond mere diplomatic niceties. This situation mirrors a 2016 agreement between Ethiopia and Somaliland and involving DP World to develop the port at Berbera, Somaliland. Despite facing significant opposition from Somalia, the project has proceeded. A 2023 World Bank report ranked Berbera as the most effective port in Sub-Saharan Africa.

Despite the risks involved, global firms like DP World, Trafigura and Taiwan’s CPC Corporation have invested millions of dollars in Somaliland. Recent collaboration with Taiwan has led to significant discoveries, such as a massive lithium deposit. Its exact size and economic viability have not been established, but foreign companies are already investing in the discovery. Australian mining businesses could engage in these promising ventures, as Somaliland has largely untapped reserves of oil and other minerals, such as gemstones, gold, iron ore, tin and lead.

The main argument against a country recognising Somaliland is that doing so can supposedly set a precedent that encourages secessionist movements in Africa. But Somaliland’s story is unique, because it gained independence from Britain initially as a state. Its context aligns with the principle of state continuity, as with the Baltic republics, which regained independence after the collapse of the Soviet Union. These nations were recognised based on their historical sovereignty and legal continuity, providing a precedent that supports Somaliland’s case.

If Somaliland were a mere secessionist movement, Ethiopia, with great ethnic diversity, wouldn’t countenance its recognition. But it’s not concerned.

Australia has been ahead of the United States, for example, in recognising new states when self-determination and democratic governance have been involved, such as Kosovo and East Timor. It is time to do the same with Somaliland.