Many Australians will remember the late NZ Prime Minister Robert Muldoon’s witticism that Kiwis crossing the Tasman raised the average IQ of both countries. Another time, after tight wage, price and currency controls, he was queried about the value at which the NZ dollar had been pegged. Our value is exactly right, he said; every other currency is out of line.

President Donald Trump’s decision on 8 May to exit the Iran nuclear deal is reminiscent of that. The Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) was painstakingly negotiated by six countries (China, France, Germany, Russia, the UK and the US). The Europeans concluded that the most critical item on the Iran file was its suspected pursuit of nuclear weapons.

They persuaded the Obama administration to isolate the nuclear program from other concerns like Iran’s ballistic missile capability and regional misbehaviour, increase the breakout time to the bomb by shrink-wrapping all dimensions of the program, and impose a stringent inspections regime to verify compliance.

Quarantining the nuclear program from other problematic items also enabled them to end Sino-Russian backing for Tehran. The JCPOA was unanimously endorsed in Security Council Resolution 2231 (20 July 2015) and widely welcomed around the world as the only bit of good news on nuclear issues in several years.

Now we’re told that everyone else got it wrong. Only Israeli PM Benjamin Netanyahu (who relies on US power to shun compromising with the Palestinians), Trump and his secretary of state and national security adviser understand the fraud perpetrated by the JCPOA. In reinstating sanctions, Washington has made itself an international outlaw for material breach of the JCPOA.

Trump has shown an uncanny knack for uniting US adversaries and antagonising and alienating US allies (except joined-at-the-hip Australia). He acts on a vision of US exceptionalism that confers global rights without the corresponding obligations. The driving force behind his exit from the JCPOA is not to keep Iran from getting the bomb but regime change in Tehran.

The Europeans had invested the most in securing the deal by effectively mediating between Iran, the US, China and Russia and have reacted with unconcealed fury. Some American commentators gallantly insist that Trump can ignore Europe because its condemnations are never matched by action.

But in the mainstream media, Carl Bildt, Edward Luce and James Traub argue that Trump’s exit from the JCPOA was ‘a massive attack on Europe’. The US ‘abandoned its belief in allies’ and may ‘the trans-Atlantic alliance, 1945–2018’ rest in peace. A Der Spiegel editorial concluded: ‘The West as we once knew it no longer exists’. An adviser to EU external affairs chief Federica Mogherini called Trump’s decision ‘an utter and unjustified betrayal of Europe’.

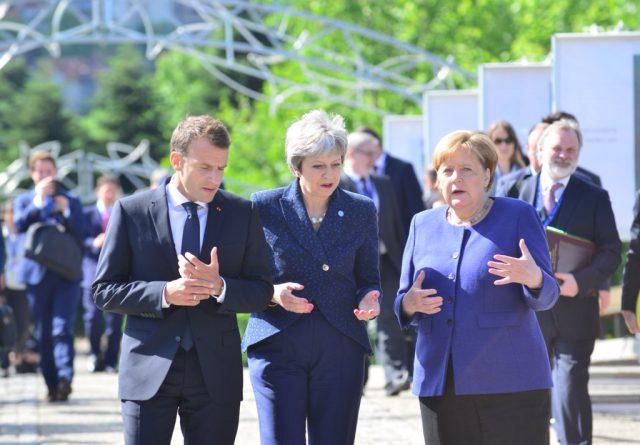

The three big Ms of Europe—French President Emmanuel Macron, UK PM Theresa May, and German Chancellor Angela Merkel—have publicly criticised Trump’s decision, closed ranks and resolved to assert a united European position. In this ‘new age of American imperialism’, French Finance Minister Bruno Le Maire called for collective action ‘to defend our European economic sovereignty’, adding: ‘Do we want to be a vassal that obeys and jumps to attention?’

Donald Tusk and Jean-Claude Juncker, president of the European Council and Commission respectively, said the threat to Europe from US ‘capricious assertiveness’ was serious. Europe must act to protect the JCPOA with EU-wide ‘blocking statutes’ to nullify US sanctions on European firms, a search for additional financial tools to permit the EU to be independent of the US, and the creation of a European agency to monitor the activities of foreign companies.

Europeans are infuriated at Trump’s one-finger send-off to the deal they negotiated with considerable pride. They fear the consequences for the US’s reputation and credibility and the harmful impact on a negotiated resolution to North Korea’s nuclear challenge. Former President Barack Obama warned that Trump ‘risks losing a deal that accomplishes—with Iran—the very outcome that we are pursuing with the North Koreans’.

The unilateral US decision forces the Europeans into a stark choice that can’t be fudged and finessed. They can accept a subservient status vis-à-vis Washington; defer to Trump’s superior wisdom, insight and judgement on Iran; and comply with the tough new US sanctions. In that case, the JCPOA is dead and Iran is liberated from all its constraints and could sprint to the bomb and seek a presidential summit with the US leader on the North Korean model.

Trump has discredited the moderate pragmatists and empowered the hardliners in Tehran who had never reconciled themselves to the JCPOA. With decades of justification for its antipathy to the US, why would Iran ever trust America again? In turn, this could create a ‘polynuclear’ Middle East as Saudi Arabia, Egypt and Turkey enter the nuclear arms race. The prospects of an Iran–Israel war have also heightened.

The alternative, less unpalatable but challenging option for the Europeans is to salvage the deal by continuing to honour their commitments on sanctions relief and assistance to Iran. European companies engaged in commercial transactions in and with Iran will need ironclad guarantees to protect them from punitive US measures for violating their extraterritorial secondary sanctions.

This is the path the Europeans seem inclined to take. We could face fresh turbulence with the onset of a trans-Atlantic trade war alongside already picked fights with China, South Korea, Japan and Russia.

The unique economic clout of the US rests in its central role in the global financial system, which even China’s growing trade profile—it’s the world’s biggest bilateral trade partner—can’t erode.

Trump’s decision to abrogate the multilaterally negotiated and UN-endorsed JCPOA, followed by threats of secondary sanctions on non-US enterprises doing business with Iran, shows that US dominance of the world financial system has become a national security threat to other countries, including longstanding US allies. While the policy implications are obvious, the will and ability to address the threat are less so.