Hugh White is right—the Australian government needs a consistent policy and message on China.

Hugh White is right—the Australian government needs a consistent policy and message on China.

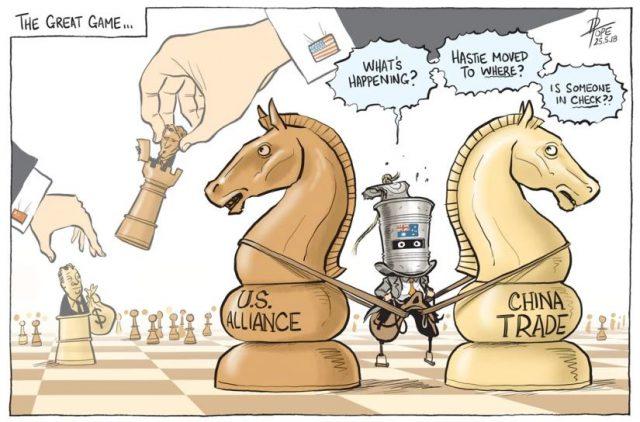

The last 10 years the message from both sides of politics has been that Australia need not choose between its strategic relationship with the US and its economic relationship with China.

Australian ministers and officials visiting Beijing have been able to talk glowingly about the ever-deepening trade and economic relationship, the growing people-to-people links, our friendship and our joint ambitions to grow things still more.

Flying off to Washington, our representatives have been equally glowing. There they speak about the continued deepening of our alliance links, the unbreakable bonds from decades of the closest cooperation, the value we see in our continued technological, intelligence, policy and strategic partnerships in national security—and our commitment to pushing back with the US and other partners against the increasingly assertive military and coercive power of the Chinese state.

This is us not choosing between the US and China.

That worked well when China wasn’t posing more direct military challenges to security in the region, and when the US was a reliable leader of its alliance and security partnerships in the Indo Pacific, Europe and the Middle East.

What changes things most, though, is Chinese policy, actions and intent. The two clear areas where this matters a lot are in the South China Sea and in the military modernisation program of the Peoples’ Liberation Army, Navy and Air Force.

The gap between Chinese Communist Party leadership statements about the peaceful intent of China in the South China Sea and the blatant militarisation of the artificial structures China has built there is breathtaking. Military airfields, high-technology military radar and signals interception facilities, hardened aircraft hangars, and the likely deployment of fighters, bombers and advanced missile systems on these artificial islands aren’t there to help save the lives of fishermen who get into trouble.

Similarly, Chinese government statements about China wanting to resolve disputed sovereignty claims in the South China Sea peacefully and by bilateral negotiations are hollow when nations with claims like Vietnam and the Philippines face this obvious militarisation.

The problem is the gap between statements, actions and intent. There’s no explanation for this but to see that the Chinese state is using its growing military power to coerce other countries like the Philippines to abandon legitimate claims to sovereign territory. This isn’t the win‑win behaviour of President Xi Jinping’s China Dream. But it is a foretaste of how China will treat other countries as its military power grows.

The second area where Chinese policy, actions and intent matter a lot to Australia is in the pursuit of military advantage through technology. The PLA’s military modernisation has been rapid and broad. It has routinely happened faster than Western analysts and experts have predicted—and been more successful.

In the last two decades, the PLA has moved from a mass, low-technology force to a professional military organisation developing and deploying leading-edge capabilities—in domains like cyber, space and high-speed missiles—and with modern surface and submarine fleets and military aircraft. More disturbingly, the Chinese state is investing billions of dollars in next-generation technologies that could disrupt the warfighting advantages that the United States still holds.

The Chinese state calls this next stage of modernisation civil–military fusion. It involves a national effort by the PLA, Chinese corporations—notably tech companies like ZTE, Huawei and Alibaba—and Chinese universities and research institutes to create the next generation of technologies aimed at delivering breakthrough military advantage—in key areas like cyber, space, artificial intelligence, autonomous systems, hypersonics and remote sensing.

The US technological advantage is one that Australia relies on absolutely with its own defence capabilities—our whole approach to defence planning and investment is based on us having access to US technologies that allow our small Defence Force to fight against larger adversaries and survive because of the edge that privileged access to US technology provides. If Chinese military technology succeeds in meeting, or in some cases overturning, US technologies, then Australia has a bigger problem than most.

So, what would a consistent Australian policy approach on China look like? It needs to work as well in Washington as in Beijing, and to have public support here in Australia. It needs to deal with the actual Chinese militarisation that we see.

Basing our policy on our interests seems the most obvious approach.

Continued economic growth is in both Australia and China’s interests, so we needn’t overturn our trade and economic interaction, but some of it will have to change.

On the flip side, Australia’s national security interests—and the interests of many other countries in our region and across the globe—are served by not assisting China to further advance its military capabilities in ways that will allow the Chinese Communist Party to coerce other nations.

This is about clear public and government-to-government statements, about international diplomacy and use of multilateral fora—whether the East Asia Summit, Shangri‑La defence ministers’ meetings, the UN and all its institutions, or ASEAN forums.

More importantly, though, acting on our interests in limiting China’s growing military capabilities has an economic and societal dimension here in Australia, and a political and trade effect on the Australia–China relationship.

Taking this interest seriously, Australian companies, research organisations, universities and government agencies shouldn’t act in ways that advance China’s civil–military fusion agenda, or that assist Chinese research organisations or universities to build PLA capabilities. Examples would be cooperation between Australian and Chinese academic institutes on artificial intelligence, machine learning and novel materials. Australian law and regulation could make Australian entities assisting research organisations with direct relationships to the PLA unlawful, with companies, individuals or research organisations who do so being subject to large fines.

Obviously, there would be whole swathes of university-to-university and corporate activity that would be able to be characterised as ‘dual use’—with artificial intelligence being a good example. However, who this research was for, not the type of research itself, would be the measure used.

Put as simply as possible, Australian policy on China would be:

We want to continue our close and growing economic relationship because it’s to both countries’ benefit: you get high-quality resources and education and tourist services at world competitive prices. We get revenue and economic activity that is important to our society.

We won’t, however, work to assist your growing military capabilities because we’re seeing that the way you’re beginning to use those, most obviously in the South China Sea, isn’t in either Australia’s or the region’s interests.

We don’t support your plans to create military advantage for China through next-generation technologies, so our economic and research interactions will have limits in this key area.

This statement of our interests, including these important differences between us, can set a solid foundation for all interactions between our peoples.

That’s a policy on China that we could state as clearly in Beijing as in Washington. It would cause outrage in the China Daily and icy calls to correct ‘outmoded Cold War thinking’ from Chinese Communist Party officials. It’d probably require Australians to diversify our markets beyond just China (no bad thing in itself from a simple economic risk perspective), and to put up with time in the official China deep freeze.

But after the outrage, the trade in iron ore, coal and high-quality education would roll on—because it’s such good business, not just for Australia, but for China as well.

This approach has large, difficult implications for Australia’s political leadership, government agencies, business leaders and academics. It will likely result in us seeing examples of Chinese coercion being applied before we reach a new way of interacting.

However, it’s a China policy that would fit with our real national interests, and which would be able to be stated consistently, whether in Washington, Beijing, Tokyo, Berlin, Jakarta or the Wollongong RSL.