Scarcity of funding threatens women’s peace work

Posted By Alba Boer Cueva, Keshab Giri, Caitlin Hamilton and Laura J. Shepherd on March 8, 2022 @ 12:30

According to preliminary data collected by the OECD [1], global foreign aid flows reached an all-time high of US$161.2 billion in 2020, as official development assistance was mobilised to support countries in the global south in peace and development work through the devastating effects of the Covid-19 pandemic. Women and women-led organisations receive a relatively small proportion of available funding, however, with a prominent 2015 review [2] of funding for women, peace and security initiatives suggesting that only 1% of funds provided was targeted towards women-led organisations, including women human rights defenders.

Over the past 18 months, we have been studying the funding of women’s peace work, as part of the Gender, Justice and Security Hub [3], an interdisciplinary research hub funded by UK Research and Innovation through the Global Challenges Research Fund. Scarcity of funding has created important political dynamics that affect the work that civil society can do. In the absence of material commitments, vital work on gender, justice and security simply won’t flourish.

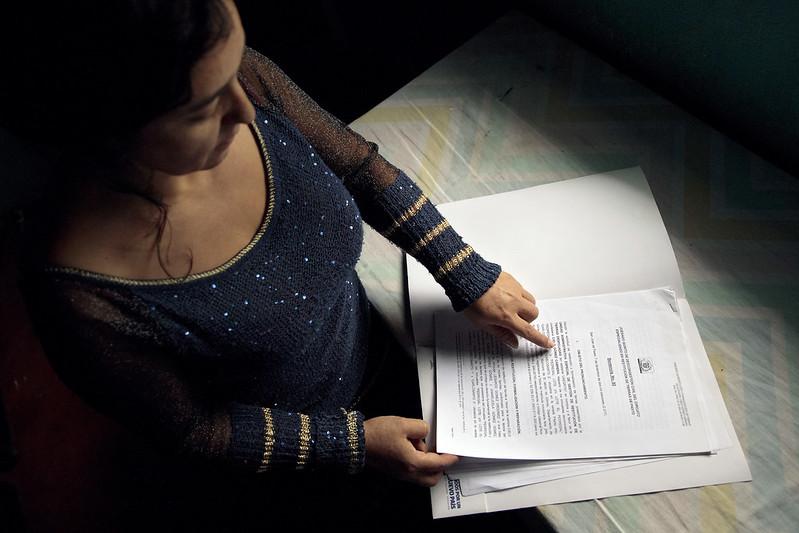

We interviewed representatives from women’s civil society organisations in Colombia, Nepal and Northern Ireland to better understand the opportunities and constraints posed by the funding of their activities, and to explore the relationships between these organisations and their donors. Across all three of these countries, we found that funding is largely project-based, made up of a patchwork of funders, and marked by year-to-year uncertainty.

Our research showed that, while it is an ongoing concern, scarcity of funding isn’t the only inhibitor to effective peace work. Donor priorities, and embedded assumptions about the value of peace work—largely undertaken by women and women-led organisations—also challenge the viability of continued efforts towards sustainable peace.

It’s easier to find funding for some areas of women’s peacebuilding than others; initiatives for countering violent extremism, for example, or particularly visible issues like conflict-related sexual violence, tend to be more appealing to donors than other areas of the WPS agenda, such as building the capacity of women human rights defenders. Unfortunately, we found that the new or popular areas of women’s peacebuilding that are particularly fundable aren’t necessarily the same areas that civil society organisations see as offering the greatest on-the-ground impact.

When we asked the organisations about the areas of their work that they would like to see funded, what they reported needing most were things like safe and reliable transport and funding to rent a hall for a meeting. In contrast, the organisations reported greater donor enthusiasm for things that can be more easily ticked off on a monitoring and evaluation matrix: ‘run 10 workshops’, for example, or ‘produce five briefing papers’—actions that are more easily measurable than ‘build trust’ or ‘create a space for meaningful dialogue’.

And yet it is precisely this building of relationships and making space to talk that organisations saw as the most important aspect of their work. Building social infrastructure is essential in achieving social justice and equality and in building sustainable peace and security. As one of our Nepalese interviewees explained to us, ‘We need to have a different kind of engagement, not like just hosting workshops, training, ticking boxes and counting how many came.’ Quite simply, we need donors to shift from investing in infrastructure and things to investing in people and relationships.

Covid-19, of course, has heightened many of the challenges faced by civil society groups. Many of the organisations that we spoke to reported an increase in violence against women—something that UN Women has described as the ‘shadow pandemic’ [4]. We also heard that key community needs were going unmet; supporting mental health [5] in particular has been an especially pressing challenge faced by civil rights organisations. The pandemic also meant that many of the face-to-face activities and programs that the organisations had planned were no longer feasible.

So, as funding has decreased, the need for these civil society organisations has only grown. We haven’t yet seen the full impact of funding being diverted from women’s peacebuilding; funding for last year was largely already in place by the time the full force of the pandemic was felt. It is only in the coming months that we will start to see the devastating impact of chronic and prolonged underfunding in the sector.

We asked our interviewees what would happen if they were able to secure sustainable funding. The response from one of our interviewees in Colombia has stayed with us; she said that, with proper funding, ‘we would flourish in an incredible way’. Securing resources for women’s peace work, to enable the kind of flourishing envisaged by the groups we worked with, is an essential foundation of gender equality, justice and ongoing security. The inclusion of women and women’s groups in peace processes and peace work in general is vital to achieving substantive and durable peace.

Article printed from The Strategist: https://aspistrategist.ru

URL to article: /scarcity-of-funding-threatens-womens-peace-work/

URLs in this post:

[1] OECD: https://www.oecd.org/newsroom/covid-19-spending-helped-to-lift-foreign-aid-to-an-all-time-high-in-2020-but-more-effort-needed.htm

[2] prominent 2015 review: https://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/UNW-GLOBAL-STUDY-1325-2015.pdf

[3] Gender, Justice and Security Hub: https://thegenderhub.com/projects/donor-funding-and-wps-implementation/

[4] ‘shadow pandemic’: https://www.unwomen.org/en/news/in-focus/in-focus-gender-equality-in-covid-19-response/violence-against-women-during-covid-19

[5] mental health: https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-021-00175-z

Click here to print.