Australia’s strategic outlook in 2021 holds both an unhappy certainty and a deep anxiety. The unhappy certainty is that China’s intent to punish us for failing to bow to its domination will continue and probably get worse.

The good news is that we now understand what needs to be done about Beijing’s bullying. The government has a tight-lipped determination to push back, as was shown this week by Treasurer Josh Frydenberg’s rejection of a $300 million takeover of the Probuild construction company by a Chinese state-owned entity.

Getting to this moment of policy clarity hasn’t been easy. It required the overturning of decades of Canberra consensus that closer engagement with China was Australia’s only path to prosperity.

With the help of Beijing’s offensive rhetoric and aggressive diplomacy, we have passed this inflection point. No federal government could reverse course and seek now to deepen our economic dependence on China.

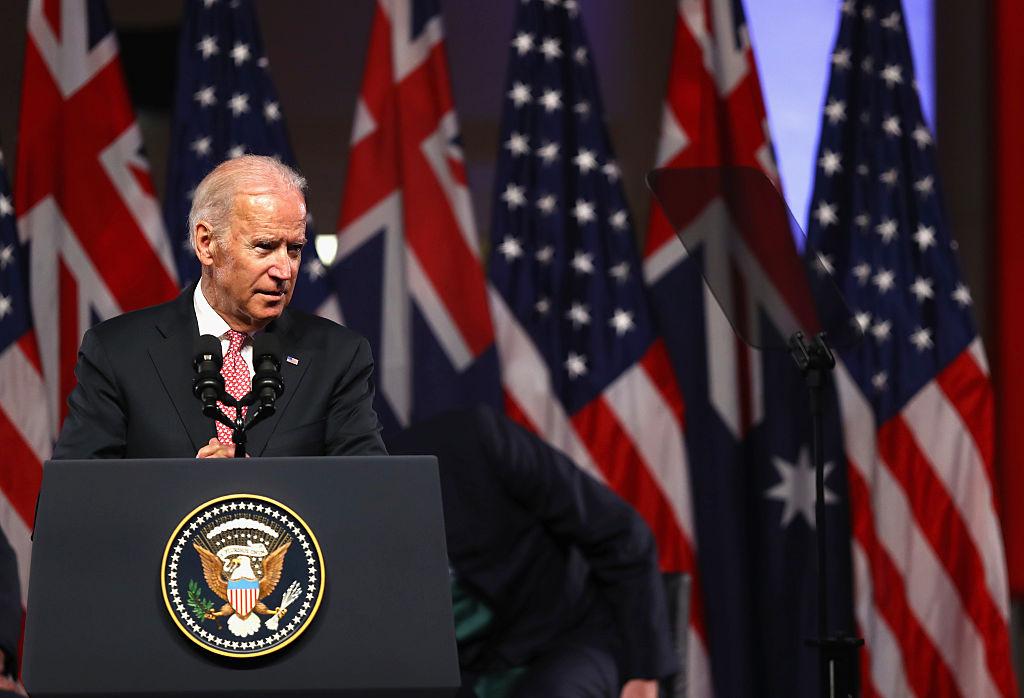

So much for certainties. The anxiety is about how the Biden administration will approach its security interests in the Indo-Pacific. Canberra decision-makers are relieved that the unpredictable chaos of Donald Trump’s foreign policy is almost over, but Trump presided (perhaps without realising it) over a US policy establishment that shaped a bipartisan consensus on China which will last into Joe Biden’s presidency.

Yesterday a 2018 National Security Council secret document, the US strategy framework for the Indo-Pacific, was released in Washington. It advocates pushing back against China, working more closely with India, and bolstering alliances with Australia, Japan and South Korea. It also discusses doing more in Southeast Asia and the Pacific islands to help democracies. All of this can easily be adopted by Biden.

Trump pushed back more effectively than his predecessor Barack Obama against Beijing’s annexation of the South China Sea and put more priority on supporting Taipei. Trump had a positive relationship with prime ministers Malcolm Turnbull and Scott Morrison that kept Australia prominent and appreciated in Washington and kept defence cooperation growing.

But Trump’s approach was flawed by a capricious unpredictability—for example, his ill-considered attempt to get Kim Jong-un to give up nuclear weapons on the promise of property developments and tourism in North Korea.

Canberra’s relief is that we dodged the worst of Trump’s criticism of America’s allies. We could easily have been targeted, as European allies were, for failing to pull our weight on regional security. Instead, Australia made the right call to keep Chinese companies out of our 5G network, pushed back against foreign interference in domestic politics and, belatedly, promoted a Pacific ‘step-up’.

These policy moves, along with just barely managing to get defence spending above the ‘acceptable’ NATO benchmark of 2% of GDP, buy interest and credibility in Washington.

Canberra’s anxiety about Biden reflects a concern about how he might drive American strategic policy. What if Biden reverts to an ‘Obama-lite’ strategy? Internally distracted by Covid-19 and a poisonous election year, might Biden look to placate Xi by not pressing Beijing on cyber spying, human rights abuses, Taiwan and the South China Sea and instead shape an agenda around climate, arms control and multilateral diplomacy?

Some of these approaches were features of an article Biden wrote for the authoritative Foreign Affairs journal in mid-2020. He said a priority for his first year would be to ‘organize and host a global Summit for Democracy to renew the spirit and shared purpose of the nations of the free world’.

Summits are an occasionally useful tool of foreign policy but no real substitute for practical action, a capable military, active alliances and a well-defined national agenda.

Biden’s second stated goal was to ‘equip Americans to succeed in the global economy—with a foreign policy for the middle class’. This seems to be a nod to the domestic ‘America first’ mood. Biden said that he wouldn’t enter into trade agreements ‘until we have invested in Americans’, that the ‘vast majority’ of troops must come home from the Middle East, and that military force ‘should be used only to defend US vital interests’.

Remarkably, Biden’s Foreign Affairs essay doesn’t mention Taiwan, perhaps the most immediate strategic problem he will face after the inauguration because of growing Chinese pressure threatening the island democracy.

The risk for Australia is that Biden will deliver a more elegantly expressed version of American disengagement of a type we have seen in the last four years. An ‘America first’ approach runs the risk of turning into an ‘America only’ strategy that cedes too much initiative to an angry and activist Beijing.

Australia will gain more from a United States that is encouraged to double down on its presence in the Indo-Pacific. The price for an active and engaged Washington is that we’ll have to step up our own involvement in the region and do our best to shape American policy thinking.

Biden has, for example, said that he wants to ‘jump-start a sustained, coordinated campaign with our allies’ to denuclearise North Korea. As a leading ally, Australia will need to develop some thinking about how to achieve that goal and the role we can play.

Whatever Biden’s reticence about America’s role, no global leader is better placed than Morrison to shape a more activist US engagement in the Indo-Pacific. Our management of Covid-19 and widely respected pushback against Xi’s bullying has bought Australia a privileged place at the alliance table.

Morrison should visit Washington soon after the inauguration to help shape Biden’s thinking about America’s role in the Indo-Pacific and beyond. If Biden is to develop a strategic approach that also serves Australia’s interests, we need to craft our place in that coalition effort. There is no more urgent Australian policy development task.

Key elements of this strategy should be a common response against Chinese economic coercion; a formalising of ‘Quad’ defence cooperation that also involves Japan and India; a shared condemnation of China’s dismantling of Hong Kong’s autonomy; an agreement to develop supply chains that shun Chinese forced labour; and combined planning to strengthen the defence of Taiwan.

The bedrock of our strategic credibility is our military and intelligence cooperation, more of which will be needed to make the alliance, now in its 70th year, fit for the purposes it must serve today. We must ask what more can be done to strengthen America’s military presence and cooperation in the region and what the Australian Defence Force can do to deter authoritarian military adventurism.

This will require more regional leadership from Australia than we have been comfortable delivering up until now, but the price of an engaged Washington is an activist Canberra. Biden’s strategic ambition is ours to sway.