The subsidiary of a Chinese defence conglomerate nicknamed ‘the Huawei of airport security’ is increasingly dominant in border-control and security-screening technologies globally.

Last month, Canada’s foreign affairs department backflipped on its plan to buy security scanners for 170 overseas embassies and diplomatic missions from Nuctech, a Chinese company part-owned by the Chinese government and once run by former Chinese president Hu Jintao’s son, Hu Haifeng. The reversal followed media coverage that provoked a review of the department’s procurement practices for security equipment.

At a parliamentary committee hearing on 18 November, Canadian government officials were grilled by MPs over the decision to entrust such a delicate security function to a company with close links to the Chinese state.

‘I’m sitting here, and I’m dumbfounded that this could have possibly happened’, said Conservative MP Kelly McCauley. ‘I’m sorry for sounding so critical, but good lord.’

The Canadian parliamentarian is not alone. There’s unease around the world about Nuctech’s growing dominance of the market for security-screening and border-control technologies, including among European parliamentarians, the US Senate Committee on Foreign Relations and the US National Security Council.

The Canadian case brings into sharp relief the changing security calculus in using technology equipment from long-established Chinese suppliers. The integration of hardware with computer networks has added a new dimension of data risk.

Security scanners in Canadian embassies might be a relatively small matter. But the widespread use of products and services from a state-controlled Chinese company with strong links to the defence sector for operational security functions in major airports and border crossings all over the world is a much larger issue.

Nuctech is the global market leader in vehicle and cargo security screening and a major player in several other security and border-control markets. It has factories in Poland and Brazil. It claims to export equipment, systems and services to 170 countries. The company intends to ‘move towards the future vision of contactless security checkpoints’, and biometrics, data and artificial intelligence are central to its products.

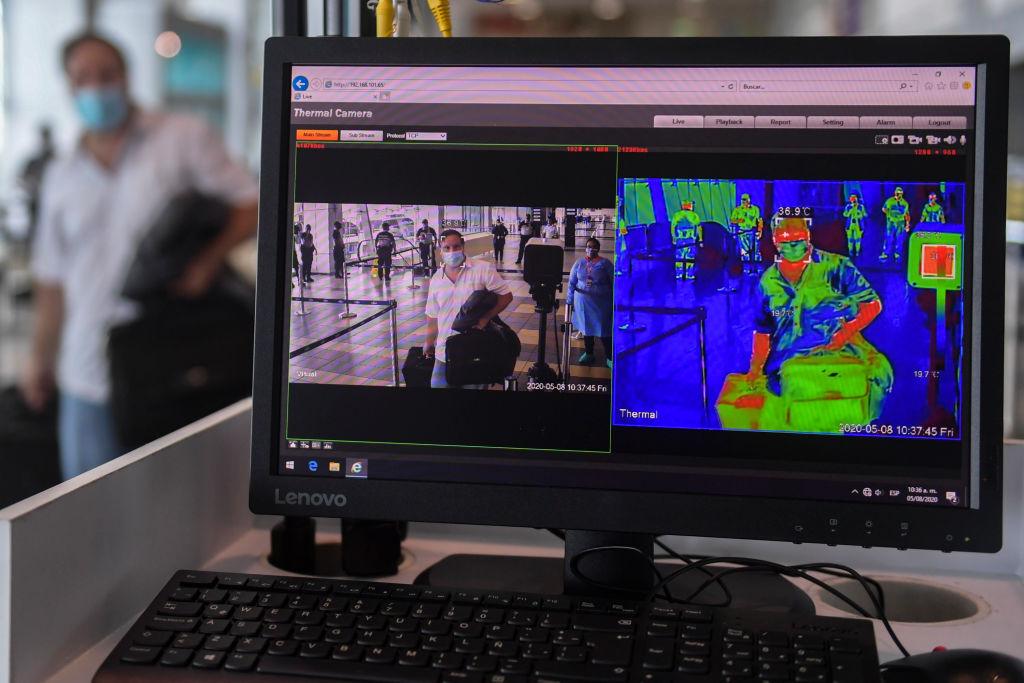

Earlier this year, responding to the pandemic, Nuctech ramped up production of its FeverBlock infrared face-temperature screening system, touting ‘thousands of orders’ for use at international airports and border posts. Data about people, vehicles and cargo crossing international borders or transiting through airports would have significant value to a range of actors, from corporations to national intelligence services.

Australian state and federal government departments have spent tens of millions on Nuctech equipment and services since the Australian customs service gave the company its first overseas order in 2001.

And, as in the Canadian case, Australia’s current processes and rules for government procurement may not take into account emerging data risks.

Chinese defence sector links

Nuctech is nested in a web of corporate relationships in China’s state-owned defence sector. Nuctech’s parent company, Tsinghua Tongfang, is controlled by one of China’s largest defence entities, the China National Nuclear Corporation, a vast state-owned conglomerate that specialises in dual-use nuclear technologies. Two other CNNC subsidiaries, the China Nuclear Power Technology Research Institute and the Baotou Guanghua Chemical Industrial Corporation, are on the US banned entity list, which restricts US companies from doing business with them on national security grounds.

A Nuctech subsidiary, FoundMacro, with which Nuctech shares a Beijing office, makes ‘counterterrorism’ products, including a vehicle-mounted microwave denial system that ‘assists secret arrest’, and an AI-enabled predictive warning surveillance system using sentiment analysis technology jointly developed with Russia.

In Xinjiang, the autonomous region in northwestern China that has been the site of mass arbitrary detention of Turkic and Muslim minorities since 2016, Nuctech is a supplier of public security equipment to the regional government and subregional jurisdictions. It has donated security equipment for use at border checkpoints and has marketed a range of products at police trade fairs including as recently as 2019. It has also fitted out the region’s highways with at least 40 sets of X-ray inspection systems and installed passenger-screening equipment at transport terminals.

Nuctech overseas

Nuctech was banned from US airports in 2014 after a confidential government report that has never been released. But in Europe, Nuctech airport-screening and public-security equipment is in wide use. Nuctech supplied security equipment to the 2020 World Economic Forum in Davos and the 2016 Olympics in Rio de Janeiro. A corruption scandal in Namibia, a bribery scandal in Taiwan and an anti-dumping action in the EU have not halted Nuctech’s increasing capture of market share in the security technology sector over the past two decades.

Wang Weidong, Nuctech’s vice president, credits the company’s innovation and good after-sales service with its success.

There are other views, most prominent that voiced by Axel Voss, a member of the European Parliament, that subsidies from Beijing have enabled Nuctech to embark on a deliberate policy of undercutting overseas competitors to fuel its dramatic global growth.

Nuctech in Australia

In Australia, Nuctech systems are installed at major ports and some airports. Nuctech has a number of contracts with state governments for the provision and maintenance of body scanners at prisons and courts. Publicly available data on the AusTender website indicates that the Australian government has done tens of millions of dollars’ worth of business with Nuctech since 2001.

In April, Nuctech was one of nine suppliers that received a standing offer from the Department of Home Affairs to supply and maintain ‘X-ray, trace and substance detection technologies for the Australian Border Force’s existing fleet of equipment’. Australian government regulatory inspection reports suggest that Nuctech, rather than the Australian government, is the ‘sole responsible authority for maintenance’ of its screening equipment installed at Australian ports.

Nuctech reported selling 100 sets of its FeverBlock infrared screening system for use in Australia and New Zealand earlier this year. Nuctech says the system ‘is suitable for rapid body temperature screening in public places … based on AI algorithms to accurately locate the face position, automatically measure the distance of the person, and perform it in real time’.

The Australian government also gifted over $300,000 worth of Nuctech X-ray machines to the Papua New Guinea customs service in 2018.

A spokesman from the Department of Home Affairs told us that the department and Border Force ‘currently only use Nuctech equipment for X-ray scanning of shipping containers’. The department did not answer questions about data-security measures.

National security risk

Nuctech’s own publicity materials indicate that the types of data at least some of its systems collect would be of interest to a range of governments and private entities. For example, its ‘land border system’ for inspecting vehicles at Kazakhstan’s Port Kolzhat, installed in late 2018, ‘automatically collected’ through the integrated system ‘vehicle dimensions, container number, gross axle weight, X-ray image, CCTV video and other information’.

The extent to which Nuctech services interlink with national border-control and customs databases, including passenger identification systems, is not clear. Its products include cargo X-ray scanners (one developed using technology created by Australia’s peak science agency, CSIRO); devices for detecting explosives and narcotics; and body scanners that incorporate a range of collection modes, including facial recognition, fingerprint scans and human body scanning ‘micro measurement’. It also sells systems incorporating ‘AI, big data and video analysis technologies to realise automatic identification of high-risk passengers’.

Any use of Nuctech’s AI or facial-recognition systems is likely to be, as part of normal operation, sending collected data to Nuctech. US security agencies appear also to be concerned that any connected security-screening device—even an X-ray scanner—could access sensitive personal or commercial databases, such as passenger travel history or shipping manifests, and transmit that information to Chinese state actors.

A European spokesman for Nuctech, sensitive to this line of criticism, wrote in Politico in October that ‘data generated by Nuctech’s products during use belongs to our customers only—the company does not have any access to it whatsoever’.

A director-general of the Canadian Centre for Cyber Security, Michele Mullen, told the Canadian parliamentary committee that the risk was not imaginary—the technology has rapidly developed and with it the risk. She said Nuctech’s X-ray machines now typically come with hard drives and USB ports, so they could conceivably be used for data downloads ‘with malicious intent’.

‘Because technology is evolving, things we didn’t use to look at, we now should start looking at’, Mullen told the hearing. ‘Capabilities … with embedded operating systems and USB ports, that didn’t used to exist on X-ray machines, now do.’

Like all Chinese companies, Nuctech is subject to the suite of national intelligence laws that require it to provide any data to the Chinese security agencies if asked. The Chinese government has systematic access to private-sector data through an extensive range of overlapping state security laws that apply to any corporation with data servers inside China. Nuctech’s close linkages with the Chinese state-owned defence sector underscore these risks.

As Australia has recalibrated its understanding of the national security risks posed by a more assertive China in the past few years, and begun to grasp the extent of alignment of Chinese corporate interests with the party-state’s global interests, the Australian government has legislated against ‘corrupt or coercive’ foreign interference, reformed its foreign investment regime and provided the university sector with guidelines on problematic research collaborations. It has banned Chinese telecommunications giant Huawei and other companies ‘likely to be subject to extrajudicial directions from a foreign government that conflict with Australian law’ from involvement in building Australia’s 5G network.

In March this year, five of Australia’s most sensitive government departments, including Home Affairs, scrambled to remove servers made by the Sydney-based company Global Switch, after its parent company, the UK’s Reuben Brothers, was acquired by a Chinese state-owned consortium, Elegant Jubilee, that claimed to be privately owned.

Ironically, the same department is outsourcing elements of border screening, with its sensitive data risk, to a company linked to a state-owned Chinese defence conglomerate. It does not appear to be uniformly considering sensitive data risks with procurement from countries that may pose cybersecurity risks.

If government procurement processes and rules are not flagging risks from foreign state-owned entities and sensitive data risks, it’s time for a framework on government procurement and other collaboration with foreign companies in sensitive sectors. Customs and border control should clearly be one of those sectors. Such a framework would identify services and technologies that may put sensitive data at higher risk and apply a thorough and uniform security assessment to companies bidding for procurement tenders in those higher risk areas.

Update: On 18 December 2020, the United States added Nuctech to its banned entity list ‘for its involvement in activities that are contrary to the national security interests of the United States’. The determination cited Nuctech’s ‘lower performing equipment’ as the reason behind the designation.