The Chinese Communist Party has a problem with women of Asian descent who have public platforms, opinions and expertise on China.

In an effort to counter the views and work of these women, the CCP has been busy pivoting its growing information operation capabilities to target women, with a focus on journalists working at major Western media outlets.

Right now, and often going back weeks or months, some of the world’s leading China journalists and human rights activists are on the receiving end of an ongoing, coordinated and large-scale online information campaign. These women are high-profile journalists at media outlets including the New Yorker, The Economist, the New York Times, The Guardian, Quartz and others. The most malicious and sophisticated aspects of this information campaign are focused on women of Asian descent.

Based on open-source information, ASPI assesses the inauthentic Twitter accounts behind this operation are likely another iteration of the pro-CCP ‘Spamouflage’ network, which Twitter attributed to the Chinese government in 2019.

Hundreds of accounts in this network have been created with the sole purpose of targeting these women; some target one woman while others target multiple women at a time. Other accounts have shifted from other topics to focus on these women, having previously shared text, images and videos that align with the CCP’s narratives. These include propaganda, disinformation and conspiracy theories surrounding the origins of Covid-19 (including sharing links to a fake ‘Milk Tea Alliance’ report), human rights abuses in Xinjiang and forced Uyghur labour, US politics and foreign policy, and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

This latest campaign, in both English and Mandarin, includes a spectrum of psychological abuse, harassment, mass trolling and threats. Some women have been bombarded with tweets on a range of topics, frequently from spam accounts accusing the target of fake news or anti-China coverage, though the tweets are often not personalised.

Other parts of the campaign are far more sophisticated and tailored. A number of women of Asian descent are being targeted by a widespread, coordinated, intimidating and malicious campaign that has been crafted to be highly personal, abusive and threatening. Content has been tailored to their individual circumstances, covering their work and personal lives. This would have required extensive surveillance of targeted individuals in order to tailor these tweets and their messaging.

These women are accused of being traitors and liars, betraying their ‘motherland’ and slandering their home country (even though many of them were born overseas and have never held Chinese citizenship). These accounts attempt to attack their physical appearance, question their credibility and the quality of their work, often in response to specific content they’ve written or produced. These parts of the campaign are characterised by high levels of personal abuse including sexist, misogynistic and racist attacks that include messages such as ‘traitors don’t die well’ and ‘traitors often come to a bad end’.

The hashtag #TraitorJiayangFan—targeting New Yorker staff writer Jiayang Fan—is one such malicious example. Fan has previously written about being subjected to Chinese propaganda and nationalistic trolling. Our research shows the latest #TraitorJiayangFan campaign was started and amplified by at least 367 inauthentic Twitter accounts beginning on 19 April. Some accounts shared videos from suspicious YouTube accounts including Lino Nissan, for example, which was created on 25 May and has only posted videos in Mandarin targeting Fan. Most Twitter accounts in this network have appropriated images of real women from other websites to use as profile images, while some accounts have used artificial intelligence to generate profile pictures. These profile images are mostly of women, but in some cases of children.

AI-generated images used by inauthentic Twitter accounts:

A lack of counter-measures by social media platforms and the governments of the countries where the women being targeted reside has allowed the operators of these accounts to constantly replenish them, seemingly undeterred, continuously using the same tactics over and over to maintain a presence on US-based platforms.

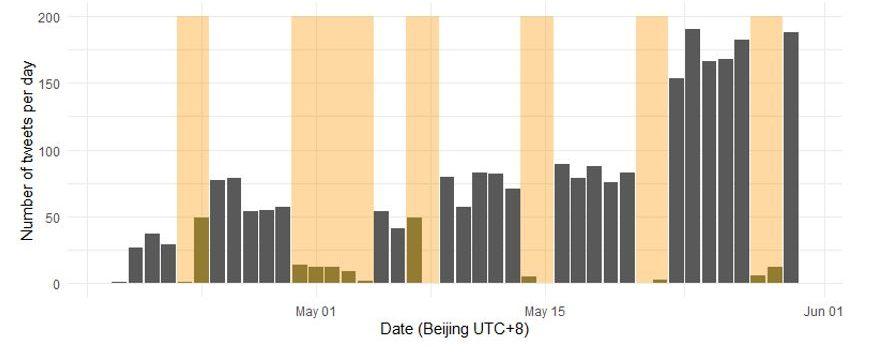

Many indicators that point to inauthentic activity linked to the Chinese state have allowed ASPI to infer similar sets of activity and track the network across multiple platforms and languages for years. Such indicators include posting content denying human rights abuses in Xinjiang, amplifying hashtags that ASPI has assessed to be other iterations of Spamouflage, using profile images similar to previous Spamouflage-linked accounts and more. Our analysis revealed the text of many of the tweets in this dataset contained double-byte characters commonly used in East Asian language fonts such as Chinese, Japanese and Korean. Most of the targeting was done during Beijing business hours and accounts were far less active during China’s 30 April to 4 May holidays.

Graph showing number of tweets per day with holidays and weekends shown in yellow:

New York Times reporter Muyi Xiao and Washington-DC-based video journalist Xinyan Yu are currently the targets of some of the most malicious parts of this campaign. Many of the Twitter accounts targeting them are linked to the same operators targeting Fan and other CCP-linked information operations (that have targeted, for example, Guo Wengui and other Chinese dissidents). Earlier this week, at least 112 different accounts posted more than 500 tweets targeting Xiao within 24 hours. Of these accounts, 54 were created on 15 April alone. Since we collected this data, it appears that Twitter has taken down some of the accounts, but not all.

This activity is escalating. Inauthentic pro-CCP Twitter accounts are beginning to harass other high-profile journalists and human rights activists including Alice Su, Mei Fong, Lingling Wei and Jane Li. These covert activities appear coordinated with a broader campaign by the Chinese government to silence women of Asian descent who have criticised its policies, or even simply reported on some issues happening in China. In March, China’s Xinhua News Agency published an article accusing Chinese journalists of helping Western media with ‘anti-China’ reports. In February, a collage of Chinese women—originally created in 2019 to target the women for their reporting of the Hong Kong protests—was shared by a Twitter account named ‘Dai Weiwei’, whose account has since been suspended. Twitter profile images of the women targeted in the latest campaigns were all present in this photo collage.

This isn’t the first time the CCP has targeted women online. Within China, women have been abused, censored, deplatformed, and sometimes even arrested for their work on women’s rights, for example. Journalists working in China have long been targeted by authorities.

Outside of China, overt and covert transnational repression is a booming industry. In 2020, our former ASPI colleague Vicky Xu was on the receiving end of one of the most sophisticated, persistent and multi-platform campaigns we have ever seen, which took place on both US- and China-based platforms. Back then, the Australian government wasn’t set up to tackle this challenge. Some departments and agencies wanted to help but couldn’t do so because they didn’t have the right legislative authorities. Others didn’t see it as a high priority or believed it to be a problem that the social media platforms should be leading on.

Over the last five years, the CCP’s online information capabilities have tended to rely on quantity rather than quality, but that’s changed and governments and social media platforms are failing to keep up. The use of more strategic, global propaganda channels, mobilising and shepherding online nationalist activity, employing and amplifying Western online influencers and amplifying Russian narratives and disinformation on Ukraine all point to an actor that is broadening its scope and targets, constantly adding to its information toolkit and evolving far more quickly than it was just a year or two ago.

The CCP’s online capabilities can now easily swing from targeting narratives and topics to foreign governments, whether they’re Xinjiang, the Quad and Japanese defence policies or US politics. It does this while also targeting organisations and individuals who play key roles in informing global public discourse on China-related issues, including Uyghur, women’s and human rights activists, as well as journalists and media outlets (including the BBC), and researchers and think tanks, among others. ASPI has regularly been on the receiving end of small- and medium-scale disinformation campaigns.

Social media platforms need to urgently shift their thinking and move from taking down these campaigns though a defensive ‘whack-a-mole’ approach, to a more pre-emptive and proactive stance. Platforms and governments need to work more collaboratively to build the infrastructure, capability and deterrence measures necessary to respond to cyber-enabled foreign interference and digital transnational repression. Both also need to work more closely with expert civil society groups in policy development and to identify networks, actors and targets.

A good first step would be for governments to more publicly denounce these malicious harassment and disinformation campaigns. The US government is the most advanced in its thinking here, having signalled this issue as a key policy focus for President Joe Biden’s administration. The White House could, for example, lead a coalition of countries in condemning digital transnational repression. A joint statement should gain support from countries and regions like Australia, the UK, Canada, Europe, Japan and hopefully others. It would signal to publics, diaspora communities, social media platforms, malicious actors and, of course, the individuals and organisations under threat, that there will be a rapid step-up in policy focus and action.

Australia can’t continue to put this in the too-hard basket. Cyber-enabled foreign interference and digital transnational repression is a rapidly emerging security challenge that will make its way into the media, and into new cabinet members’ briefing packs and intelligence assessments, far more than it has before. Luckily, the Senate’s multi-year effort looking at foreign interference through social media puts the new government in a strong position to hit the ground running—but its efforts will need to be consistent and they will need to keep up with the ever-evolving nature of the challenge.