‘Brothers and sisters—our region has not faced a more vexing set of circumstances for decades. The triple challenges of climate, Covid and strategic contest will challenge us in new ways. We understand that the security of any one Pacific family member rests on security for all.’

— Foreign Minister Penny Wong, speech to Pacific Islands Forum secretariat, Suva, Fiji, 26 May 2022

As ever, the South Pacific islands know they need Australia—although, as ever, that doesn’t mean the islands have to like that need. Or be happy about the central role Australia must play as times get tougher.

Australia’s sharper focus on what it needs in the South Pacific is partly matched by the region’s apprehensive understanding of what it faces.

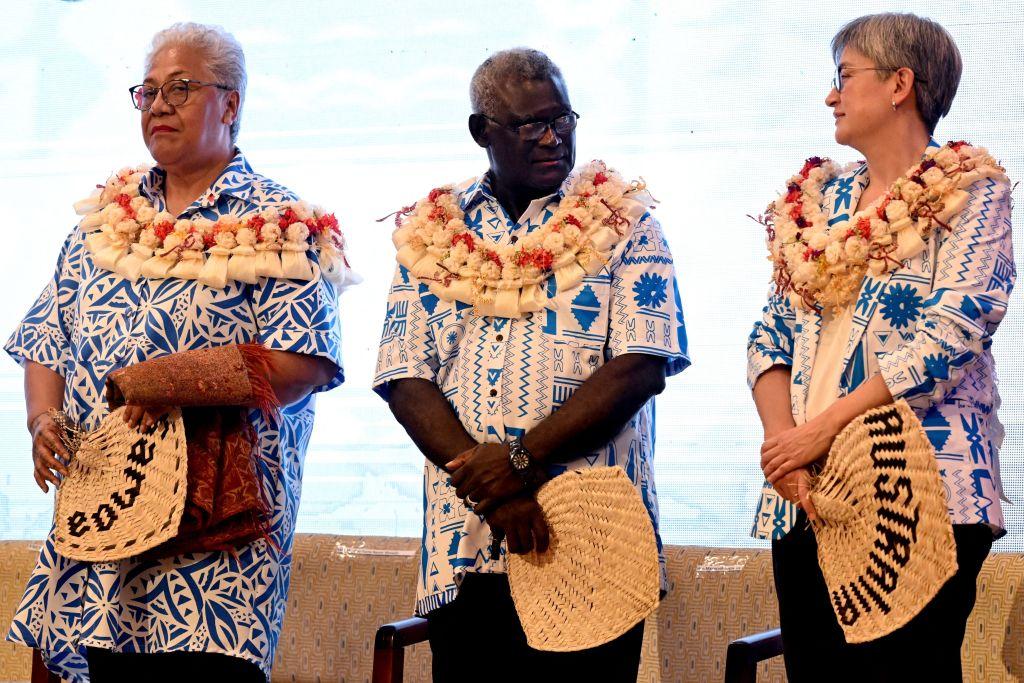

Since being sworn in as foreign minister on 23 May (two days after the election), Penny Wong has crisscrossed the South Pacific—Fiji twice, Samoa and Tonga, New Zealand and Solomon Islands. On her third day in the job, her first major speech was to the secretariat of the Pacific Islands Forum.

No previous Australian foreign minister has spent so much time in the islands in their first two months. Wong’s travels represent a diplomatic duel with China’s foreign minister, Wang Yi, who had just done his own trek through the islands. The Pacific is now a place for active and direct strategic competition.

Six years as the opposition’s shadow foreign minister gave Wong a close view of those ‘vexing’ forces (synonyms: troublesome, disturbing). Australia’s Pacific step-up reaches its sixth birthday in September, so a lot has happened during Wong’s watch as shadow minister. Now she gets to run the mechanism of a major Australian policy response that’s still an ambitious work in progress.

History and geography are at the heart of the step-up, even as it’s driven by the duel. Canberra commits greater attention along with increasing amounts of cash. The galvanising element is China’s challenge to Australia’s traditional place as the pre-eminent South Pacific power.

The step-up has two drivers: the many things the islands need and the need to respond to China’s expanding power.

In setting out the three vexing challenges, Wong can tell a different story on how the new Labor government will deal with climate change. That’s made a significant difference to the atmospherics and the substance of discussions with the islands. At the summit of the Pacific Islands Forum, Australia and New Zealand could play their traditional role of good cop and good cop.

In her first-up Pacific speech and during the summit, Wong played climate as a trump card and a symbol of Australia’s role—a major point of regional agreement rather than difference:

As Australia’s first-ever climate minister, I know the imperative that we all share to take serious action to reduce emissions and transform our economies. Nothing is more central to the security and economies of the Pacific. I understand that climate change is not an abstract threat, but an existential one.

On Covid and contest, Wong can deploy another c-word: continuity. Labor picks up much of the previous government’s Pacific language, and not just the ‘Pacific family’ usage.

Symbolism and substance came together during the forum summit with the announcement that Australia’s Telstra had finalised the acquisition of Digitel Pacific, serving Papua New Guinea, Vanuatu, Fiji, Samoa, Tonga and Nauru.

In a break with the ‘privatisation’ orthodoxies of the past 40 years, Scott Morrison’s Coalition government bought Australia a Pacific phone company. Anthony Albanese’s government nods at a sound piece of policy, even with a hefty price tag. The China contest will cost lots of cash.

Foiling any Digicel flirtation with China cost the equivalent of A$2.1 billion. Canberra threw in US$1.33 billion, via the federal government’s Export Finance Australia. Telstra put in US$270 million but gets 100% of the equity. Telstra got the gift; Canberra pays. Government documents on the Digicel deal suggest a frantic on–off effort at whacking that China mole.

Wong’s use of the phrase ‘strategic challenge’ is merely a polite framing of China. And Wong’s description of what Australia can do with the island amounts to a compare-and-contrast damning of what China offers:

Australia will remain a critical development partner for the Pacific family in the years ahead. We are a partner that won’t come with strings attached, nor impose unsustainable financial burdens. We are a partner that won’t erode Pacific priorities or institutions. Instead we believe in transparency. We believe in true partnerships. We will respect Pacific priorities and Pacific institutions.

The climate–Covid–contest list of vexations can be an alliterative nod to the notion of the South Pacific as an ‘increasingly crowded and complex region’—the phrase used in the forum communiqué in 2018.

The communiqué this year reflected on 50 years of regionalism, highlighting that ‘the Pacific Islands Forum stands at a critical juncture in its history’, amid ‘intensifying geostrategic interest’. The range of challenges ‘exacerbate the region’s existing vulnerabilities and dependencies’:

Leaders noted that the region continues to be a highly contested sphere of interest, in a wider geopolitical setting with external powers seeking to assert their own interests. In the current strategic context, Leaders recognised the importance of remaining unified as a Forum family to address common challenges and to capitalise on key opportunities.

China makes ambitious offers to South Pacific states. Australia’s great counteroffer is to South Pacific people.

The political strength of the Australian offer is that it’s the bipartisan consensus of Labor and the Coalition. The dollars going to the South Pacific express the sense of the Canberra consensus. And Australia’s understanding of what’s going to be a long strategic contest.