A significant rise in Indonesian illegal fishing in Australia’s northern waters highlights a significant maritime security threat, and our border enforcement agencies can’t afford to drop the ball.

Over the past six months, Australian authorities have confiscated more than 600 kilograms of trepang (sea cucumber) from Indonesian fishing vessels in our waters. Overfished and valuable, Australian trepang sells for $15–30 a kilogram in Indonesia.

The trepang trade between various Australia’s First Nations peoples and Indonesia’s orang Makassar from Sulawesi has been well established since before Australia’s colonisation. That activity is now recognised in native title jurisprudence.

But these modern-day illegal fishers use contemporary fishing equipment and pose a threat to coral reefs, marine conservation and maritime border security.

Responding to the incursions, Australian authorities burned the three least seaworthy of the offending boats last month. That’s consistent with Australia’s (and Indonesia’s) punitive procedures for illegal fishing. Over the past 20 years, Australia has destroyed around 1,500 boats engaged in illegal fishing in our waters and prosecuted more than 2,000 foreign nationals involved (mainly Indonesian).

Australia’s approach to illegal fishing in its waters has been highly effective. From the height of the problem in 2006 when 367 foreign fishing vessels were apprehended, incursions in recent years have been in the single digits. But the rate of illegal fishing activity has soared in the past six months: 209 legislative forfeitures (which can include fishing gear, catch, salt for trepang processing, and sometimes the vessel itself) have been undertaken since 1 July. Some of these forfeitures include recidivist fishing vessels that have been interdicted multiple times.

Push factors in Indonesia have increased the fishers’ need for quick cash. The fishers hail from East Nusa Tenggara, a collection of more than 1,000 islands in eastern Indonesia. The remote region is often the first to suffer and the last to recover from a crisis. That’s been demonstrated recently by major delays in the Covid-19 vaccine rollout there.

Local poverty has been exacerbated by the pandemic’s economic impacts, which may drive a further 1.3 million Indonesians into poverty. Many worked in Bali’s tourism sector, but, like thousands of Balinese, they’ve moved to their home villages after widespread pandemic-related layoffs. The fishing industry has also contracted by 11%. That’s pushed the incentives for illegal fishing. In April, Cyclone Seroja levelled 20,000 homes and buildings in Nusa Tenggara, killing hundreds. These conditions pushed local fishers to venture further to regain their losses.

The Australian Fisheries Management Authority’s five-pronged international compliance and engagement program seeks to address illegal fishing through surveillance and enforcement operations, interagency and high-level communication, information sharing and stakeholder engagement. It emphasises public information campaigns in relevant overseas ports.

The program’s strength has been its cohesive and multifaceted approach: punitive action is balanced with education campaigns for domestic and international communities on legal best-practice fishing. Key partner agencies include Parks Australia; Maritime Border Command; the Department of Agriculture, Water and the Environment; the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade; and the Royal Australian Navy.

The overall strategy has incorporated government partnerships and multilateral forums, notably the Australia- and Indonesia-initiated regional plan of action to promote responsible fishing and combat illegal fishing in Southeast Asia. It’s been a coordinated top-down approach and helped put the issue on the agenda in a recent meeting between Prime Minister Scott Morrison and Indonesian President Joko Widodo.

But the pandemic has significantly hindered the coordinated and integrated approach that’s kept illegal Indonesian fishing in our waters at low levels over the past 15 years.

Vessel seizures have continued throughout the pandemic (12 in 2020–21 and 28 so far in 2021–22). Due to Australian Covid-related quarantine rules, however, fisheries enforcement authorities have only been able to conduct legislative forfeitures, destroy boats and chase boats out of Australian waters; they haven’t been able to apply normal enforcement procedures through the detention and prosecution of foreign crews onshore.

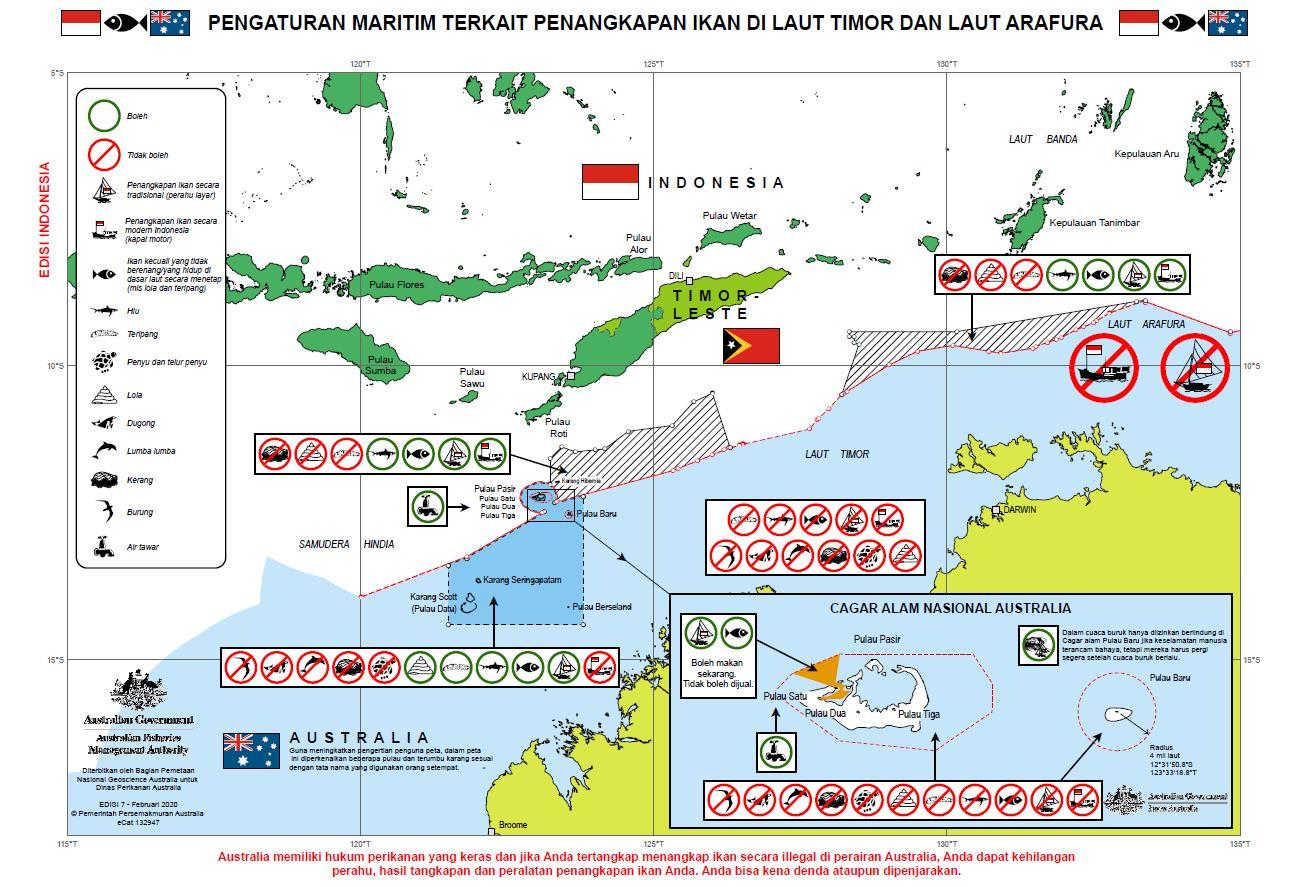

Australian authorities haven’t been able to communicate as easily with their overseas counterparts to coordinate responses and drills. In-country information campaigns have slowed down, although Australia is still working with Indonesian authorities to provide Indonesian-language information chartlets to fishers in key Indonesian ports and during routine at-sea boardings by Australian authorities.

Australia and its archipelagic neighbour are well placed to cooperate in responding to the problem of illegal fishing due to their shared security and economic interests. These interests are perhaps even more critical for Jakarta than for Canberra. The fishing industry contributes 2.65% of Indonesia’s GDP, and the nation’s maritime border security has been tested by Chinese naval vessels in the contested Natuna Sea.

Both nations have strong regional policies on the issue (articulated through the regional plan of action) and cooperate bilaterally through drills like Operation Jawline Arafura. Australia’s Maritime Border Command works with Indonesia’s Ministry of Maritime Affairs and Fisheries to patrol and target illegal fishing along our shared maritime border. Tough crackdowns on illegal fishing are popular in Indonesia. To combat ongoing illegal fishing incursions by Vietnam and Malaysia, former Indonesian fisheries minister Susi Pudjiastuti led prolific and well-publicised boat destruction campaigns.

It’s in Indonesia’s interests to be a regional leader in combatting illegal, unreported and unregulated fishing, including by cooperating with Australia. Recent confusion in Indonesia about Australian authorities’ boat burnings led Jakarta to delay the usual Jawline Arafura exercise until an explanation was provided. Ironically, Jawline Arafura is exactly the kind of bilateral patrol that’s crucial to responding effectively to the illegal fishing problem. Fortunately, the problem was resolved and the exercise went ahead. But misunderstandings like these could stymie future cooperative opportunities with Indonesia on shared ocean interests.

Australia should continue to advance its diplomatic efforts with Indonesian authorities on common maritime enforcement issues. At the same time, Canberra should stress to Jakarta the need to take flag-state responsibility; Indonesia has to be able to control its own fishing fleet.

There’s more at stake here than environmental damage and millions of dollars in economic losses. In coming decades, rising ocean temperatures are set to continue to displace fish populations across maritime Southeast Asia. That will push valuable fisheries further south to cooler waters, and fishers will follow. Australia will need to add more ballast to relations with the Southeast Asian countries from which further incursions targeting our marine living resources will likely come.