For over a century, Australian federal governments have periodically tussled with the question of what to do with, and at times how to defend, what they’ve long considered Australia’s underdeveloped and underpopulated north. The Australian government’s sporadic northern foci have over time led to the development and delivery of a long list of infrastructure investments and new policy initiatives.

Regularly, to the detriment of the Northern Territory, the benefits of those investments fail to be fully realised. The driver of this underperformance is probably the stopgap nature of Canberra’s commitments to developing the north, which favour short- to medium-term economic gains. It appears that this dynamic is once again playing out in Defence’s strategic posture in northern Australia.

In his 1986 review of defence capabilities, Paul Dibb argued that, ‘If we are to project credible military power in the most vulnerable part of the continent, we require a larger permanent presence in the north of Australia.’ Over the first decade following the release of the landmark 1987 defence white paper, and its ‘defence of Australia’ concepts, Dibb’s thinking would shape Defence’s force posture in Australia’s north. Bit by bit, the ADF moved army and air force units to the Northern Territory, eventually establishing Headquarters Northern Command as a fully functioning operational command.

On paper, the Australian government has made a strong declaratory commitment to northern Australia. The 2015 white paper on developing northern Australia included a pledge to strengthen Defence’s presence in the region.

The 2016 defence white paper stated: ‘Investment in our national defence infrastructure—including the Army, Navy and Air Force bases in northern Australia, including in Townsville and Darwin, as well as the Air Force bases Tindal, Curtin, Scherger and Learmonth—will be a focus.’

It also predicted that Defence’s presence and investment in northern Australia would gradually increase. Defence is still looking to upgrade the Bradshaw Field Training Area (Northern Territory), Robertson and Larrakeyah Barracks (Darwin) and RAAF Darwin, albeit with a much smaller budget.

In contrast with these grand statements, there’s a growing body of evidence to suggest that there’s an expanding gap between declaratory policy and actual Defence activities and presence in the north. While funding might be earmarked for facility upgrades in the Northern Territory over the next few years, there will be fewer defence personnel, exercises and units there to use them.

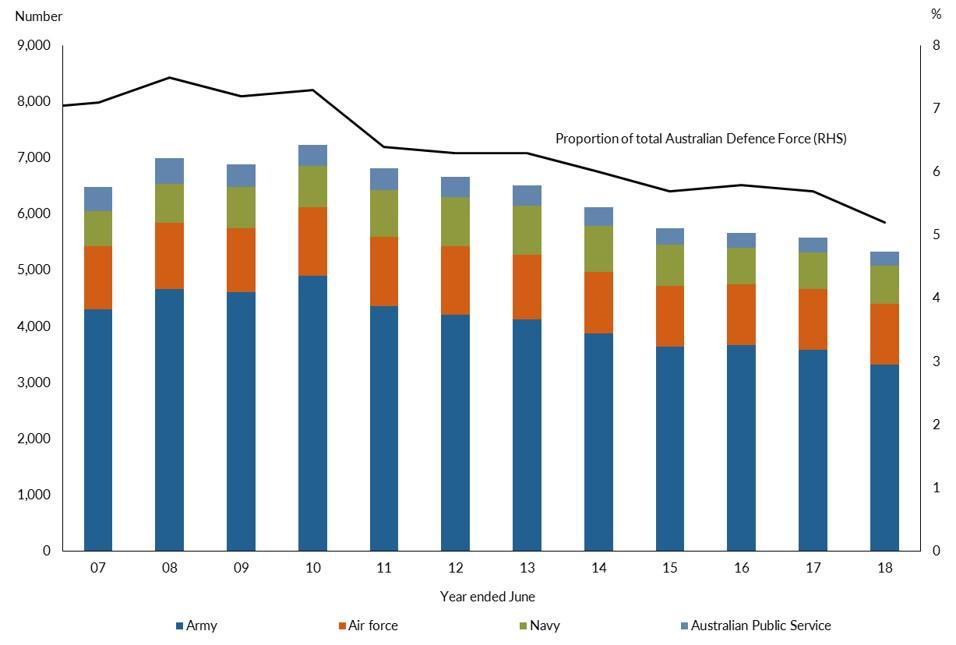

To start, Defence annual reports reveal that the number of personnel in the Northern Territory is already at an 11-year low (see figure below).

Defence personnel in the Northern Territory, 2007 to 2018

The large national-level tri-service exercises, such as the Kangaroo and Crocodile series, that once focused on the defence of Australia’s north have ended.

Headquarters Northern Command’s responsibilities have been downgraded, and command has become a part-time role for the commander of the Darwin-based 1st Brigade.

The unchanged environmental challenges of wet seasons have become, over recent years, a justification to move whole units and capabilities—such as the tanks of the 1st Armoured Regiment—south to Adelaide. The 7th Battalion of the Royal Australian Regiment, along with supporting subunits from the 8th/12th Regiment, 1st Combat Engineer Regiment and 1st Combat Service Support Battalion, has moved to RAAF Base Edinburgh, just outside Adelaide.

These changes seem incongruous at a time when the US is continuing to implement its force posture initiatives in northern Australia.

Of course, a lot has changed since the 1987 white paper was drafted, and it wasn’t legally binding. However, there’s been little public discourse to suggest a reduction in the strategic importance of northern Australia.

As I noted in January, many of the factors that have shaped the assumptions of our ‘defence of Australia’ strategies have changed substantially, and in many cases even deteriorated, since 1987.

China’s projection of soft and hard power across Eurasia and its waters, at a time when the dynamics between the globe’s great powers are changing, is creating increased strategic uncertainty. The likelihood and consequences of miscalculations are rising.

Today, the security of the north is just as important to Australia’s national security as it was in the 1930s when Japan invaded Manchuria. In this environment, Defence is placing renewed emphasis on the 2016 white paper’s first strategic objective: ‘to deter, deny and defeat any attempt by a hostile country or non-state actor to attack, threaten or coerce Australia’.

Clearly, the ADF’s slow move south needs to be not just arrested but reversed. It may be easier and cheaper to raise, train and sustain capabilities in Australia’s southern states but, as stated in the 2016 white paper, the ADF’s significant presence in northern Australia is an important part of Defence’s strategic posture. The first step in achieving that outcome is for Defence to develop a single shared policy position on its presence in the north.

Arguably, security in the north isn’t just about boots on the ground and infrastructure development, but the promotion of economically and socially flourishing northern communities. The development of industry capacity in Australia’s strategically important north is critical for defence and national security. Policy success is predicated on the Australian government making a long-term strategic commitment to northern Australia and its economy.

In bridging the gap between policy and action, the government would do well to pay heed to three lessons from its historical northern experiences:

- To be successful in the north, you must be there for the long haul.

- Building a resilient and secure north depends on creating social and economic prosperity.

- Defence’s social licence to operate in the north can’t be taken for granted.