Below is an extract from ASPI’s publication Strike from the air: the first 100 days of the campaign against ISIL released today.

Most assessments of the US-led military operation in Iraq have criticised the limited use of air power and ‘boots on the ground’ against ISIL fighters. This strategy is seen as ineffective to ‘destroy’ ISIL and to restore political stability in Iraq. Instead, critics have called for the ‘decisive’ use of air power and increased ground forces. However, such criticism fails to recognise the bigger strategic picture behind the US approach to the conflict. It also doesn’t acknowledge that the military campaign is long-term, iterative and incentive-based, and is aimed to manage the threat by ISIL rather than defeat it. While the strategy certainly faces significant risks and challenges in the future, President Obama’s measured approach shouldn’t be dismissed lightly.

After the experience of spending significant blood and treasure in Afghanistan and Iraq for limited returns, the American public increasingly supports a grand strategy of restraint when it comes to ‘wars of choice’. By and large, there’s bipartisan scepticism about a massive military re-engagement and nation-building in Iraq. This is also emblematic of the fact that, while ISIL constitutes a security problem, it’s not an existential threat to the US and most coalition partners (including Australia). That is, even if ISIL can’t be defeated permanently, it might be sufficient to ‘manage’ the threat.

Moreover, a key lesson learned from more than a decade of fighting ‘small wars’ in Iraq and Afghanistan is that long-term success depends ultimately on political conditions in the host country. Even a large military footprint and billions of dollars in civilian assistance didn’t generate lasting solutions. Iraq’s track record is very poor, indeed. One key factor of ISIL’s success has been the failure of the previous Iraqi regime to develop effective state structures. Indeed, in many ways it systematically undermined them. Chances are low that repeating a costly and lengthy US-led intervention would be successful this time, given the complicated political and socioeconomic dynamics in Iraq, as well as the ambiguous role played by powerful neighbours such as Iran.

In combination, these factors have led the Obama administration to pursue a different Iraq strategy in 2014 compared to the 2003 war. On a grand strategic level, the US is sending a signal to the Middle East that this time it won’t fight ‘other people’s wars’. Instead, Washington will conduct a long-term, light-footprint campaign (PDF), focused on supporting those groups in Iraq that are willing to fight for their country and work towards a political solution.

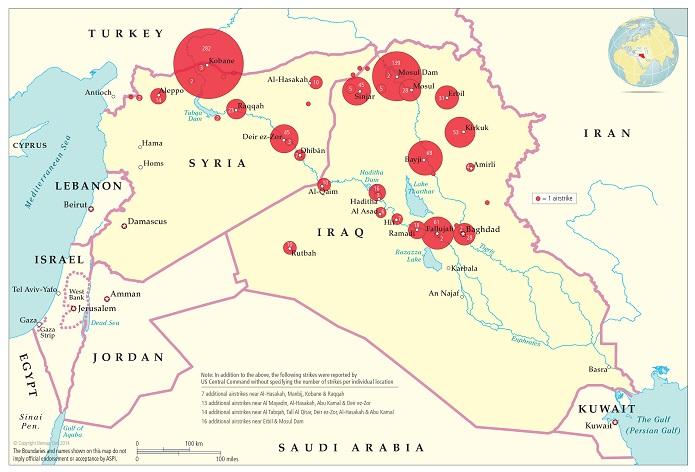

The military strategy has also been designed from the start to be iterative. Both Obama and the US military leadership have been careful in stating that air power alone is insufficient. Rather, in the first ‘advise and assist’, airstrikes have been a primary means and have arguably had some success in halting ISIL’s momentum and preventing the fall of Baghdad. In particular, they’ve stopped the advance of ISIL fighters in many areas and forced them to adapt their tactics through dispersal and concealment. It’s fair to conclude that the air campaign—in combination with some ground operations conducted by mostly indigenous forces—has put ISIL on the defensive.

Admittedly, the strategy carries significant risks. The second phase (‘building partner capacity’) will be much more protracted and risky, and the outcome is more uncertain. It requires the coalition to provide more training and mission assistance to local forces on the ground (thereby increasing the risks), to strengthen its human intelligence capacity and to conduct close air support. It also depends on the ability to rapidly build up a sizeable and combat-capable indigenous force able to operate with diverse groups, including Iranian special forces. It remains to be seen whether indigenous Iraqi forces will be able to start ‘rolling back’ ISIL forces across the country as planned by next year.

The third phase (sustained ‘security sector reform’ in Iraq) will be even more challenging, particularly since it’s not clear yet what the political end-state would look like. Will the political actors in Iraq be able to reconcile their differences and launch a joint approach against ISIL? What’s an acceptable role of Iran in the future of Iraq?

And the coalition has to make some very tough choices on Syria, since the conflicts are interconnected. Particularly, the future of Syrian President Assad is a conundrum, given that many Arab countries want to see him removed while powerful players, such as Iran and Russia, remain loyal to him. As a result, the Obama administration has reinforced its efforts to find a Syria strategy to deal with the ISIL problem.

The military campaign is still in search of a viable political endgame in both Iraq and Syria. In the long term, this problem might render the coalition’s efforts rather futile. Nevertheless, at this point it’s difficult to perceive a politically acceptable alternative strategy.

Benjamin Schreer is a senior analyst at ASPI and a co-author of Strike from the air: the first 100 days of the campaign against ISIL. Image (c) Demap. Used with permission.