Below is an extract from ASPI’s publication Strike from the air: the first 100 days of the campaign against ISIL.

Below is an extract from ASPI’s publication Strike from the air: the first 100 days of the campaign against ISIL.

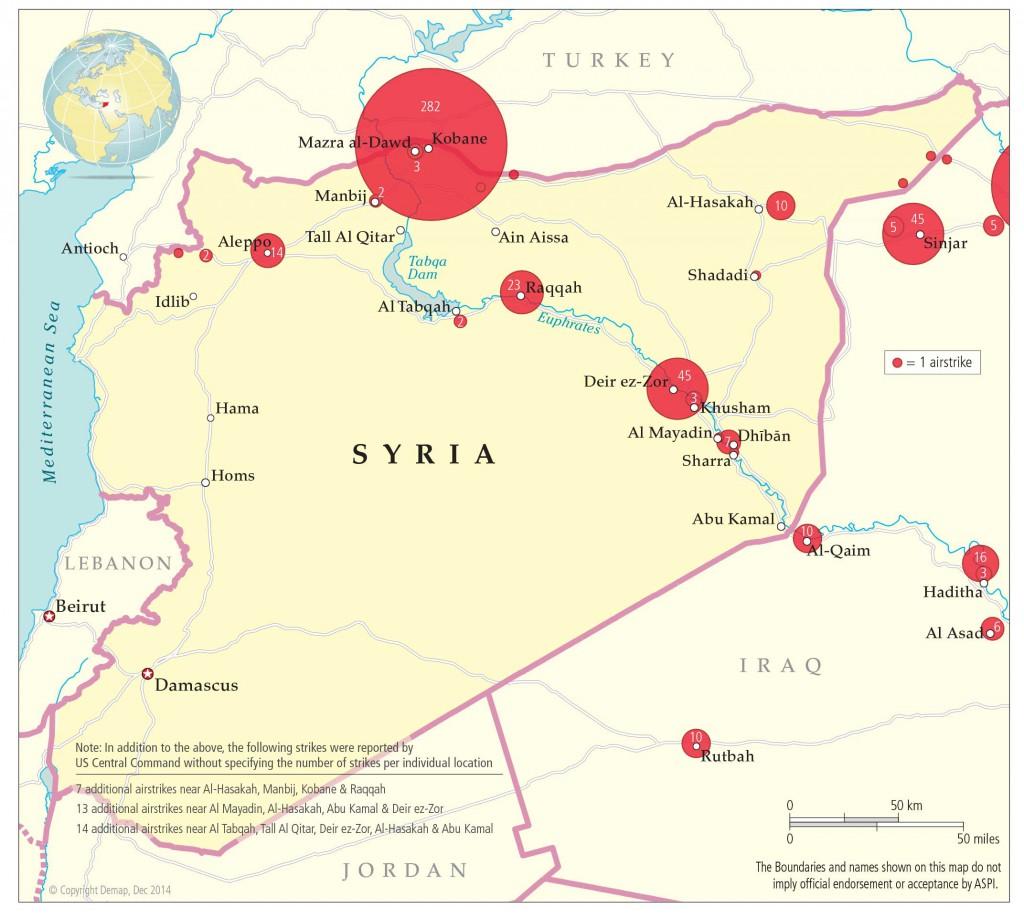

The international coalition has managed to degrade but not destroy the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL) through an air campaign that’s involved around 1,000 strikes in the first 100 days of the operation. In Syria, ISIL has secured control of the city of Raqqah and much of the northern third of the country. Its control of oilfields at Deir ez-Zor has helped it to fund its operations through the sale of oil on the black market. It appears that the group moved much of the US-sourced military equipment abandoned by the Iraqis into its Syrian strongholds and used it in a sustained, largely conventional-force, attack on the town of Kobane on the Syrian–Turkish border.

Syria is reportedly (PDF) the home of around half of ISIL’s fighters. The absence of Western intervention has made the northern part of the country an effective safe-haven. It was the staging ground for the January and June attacks into Iraq and remains the key to ISIL’s aspirations for long-term success.

The challenge for the US and coalition countries has been to design a strategy that weakens ISIL but doesn’t lend comfort or direct assistance to Syrian President Assad. The US remains wedded to the policy that it won’t put boots on the ground in Syria. The combination of those constraints makes developing coherent strategy almost impossible.

There’s no greater clarity about the plan to train a force of around 5,000 ‘vetted’ Syrian fighters. Saudi Arabia may be the training ground, but we don’t know who’ll be trained, what they’ll be trained to do, what military capabilities the force will have, and what difference such a force might make against much larger Assad loyalist forces (numbered at around 100,000 fighters) or ISIL. The US has indicated that vetting Syrians to find acceptable fighters and training them will take months. Pentagon spokesman Rear Admiral Kirby referred to this process as ‘a year-long pipeline of training opportunities’. At the earliest, US-backed ground operations involving the 5,000 ‘moderate’ fighters might be able to start around the beginning of 2016. A US presidential election year is an unpropitious time to start a major new military campaign. The recent defeat of the US-backed Syrian Revolutionary Front and Harakat Hazm in Idlib Province indicates that US support appears to be too little, too late.

Coalition airstrikes began in Syria on 22 September. Late that month, the US used the F-22 Raptor on its first combat operation since it entered service, possibly in anticipation of the need to attack remnant Syrian air defence capabilities but equally possibly, as one analyst speculated, to ‘take the bubble wrap off’ the aircraft. A remarkable array of aircraft and precision weapons were used in the strikes, which were notable for the involvement of Bahrain, Jordan, Saudi Arabia, Qatar and the UAE (Australia has limited its airstrikes to Iraq). Initial strikes, including with cruise missiles, were directed at Raqqah. Over October, the UK-based Syrian Observatory for Human Rights said that 521 Islamist fighters, including 464 from ISIL, were killed in Syria as a result of coalition airstrikes, most of them in Raqqah. The US indicated that a particular object of the targeting had been to disrupt ISIL oil production and financial activities. ISIL forces at the Deir ez-Zor oil refinery were struck regularly during September and October.

By far the greatest concentration of airstrikes in the first 100 days of the campaign was directed at ISIL forces ‘besieging’ the Syrian town of Kobane, on the border with Turkey. Major strikes took place almost every day of October and into November as ISIL continued to throw a major portion of its fighters into its attempt to take the town. The US CENTCOM Commander, General Lloyd Austin, said on 17 October that ‘If he [ISIL] continues to present us with major targets, as he has done in the Kobane area, then clearly, we’ll service those targets, and we have done so very, very, effectively of late.’

The concentration of ISIL’s effort on Kobane is puzzling. Some have speculated that it wanted to control a border crossing into Turkey, but the Turks quickly closed the border, stationing armoured units in what’s an ethnically Kurdish area. ISIL’s massing of forces in a way that made them easier targets appeared to be a tactical error, but it’s clear that even under multiple daily airstrikes ISIL fighters were pressing the town’s Kurdish defenders hard. At best, the campaign could be declared a stalemate.

Peter Jennings is executive director of ASPI and a co-author of Strike from the air: the first 100 days of the campaign against ISIL. Image (c) Demap. Used with permission.