The idea of awarding medals retrospectively to soldiers, sailors and fliers who died courageously decades ago is fraught and complex because wars have left in their wake so many whose heroic deaths were unseen and unsung.

But the case of 18-year-old Ordinary Seaman Teddy Sheean, a gunner in the Royal Australian Navy during world War II, has a special poignancy, and a clear precedent.

On 1 December 1942, Sheean was a gunner aboard the Australian warship HMAS Armidale, which was attacked by Japanese aircraft.

As the corvette began to sink and its crew abandoned ship, Japanese aircraft began strafing survivors in their life rafts. Sheean, thought to be already wounded, strapped himself into a gun and blasted the aircraft. Survivors said he shot down one aircraft and damaged two more.

As the corvette slipped below the waves, Sheean kept shooting and a stream of tracer bullets was seen bursting through the surface.

For reasons no one has ever adequately explained, the Tasmanian teenager was never decorated appropriately for his heroism. He was rewarded with a Mention in Dispatches, long regarded by his family as an insult given his sacrifice.

They and many others believed Sheehan should have been awarded the Victoria Cross. That view was reinforced by the outcome of a very similar battle two years earlier and a hemisphere away.

On 4 July 1940, German dive-bombers attacked the British anti-aircraft ship HMS Foylebank in Portland harbour. One of many bombs killed all of the members of a gun crew except for Leading Seaman Jack Mantle, 23, whose leg was shattered.

Mantle crawled back to the damaged gun, got it firing again and, some witnesses say, shot down one of the attackers before he was fatally wounded.

He was awarded the Victoria Cross for his extreme gallantry under fire.

Of the 100 Victoria Crosses awarded to Australians before Teddy Sheean, 96 were won by soldiers and four by airmen. None has gone before now to the navy. While the army and the RAAF were under Australian control during World War II, the navy was under the authority of Britain’s Royal Navy.

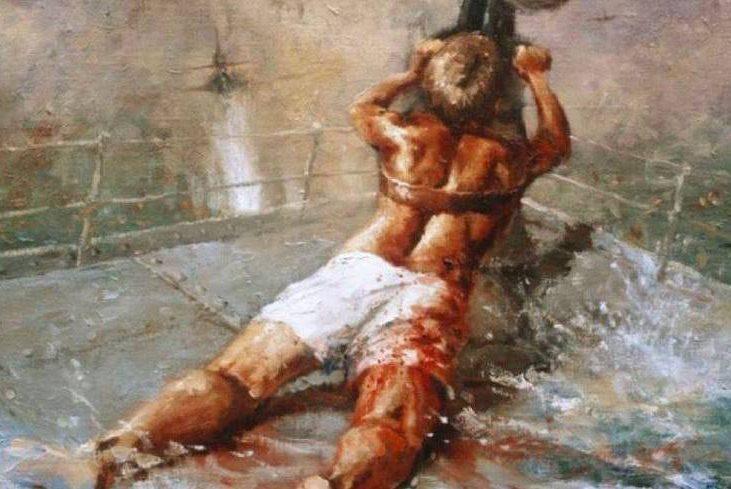

There is a suspicion that in Sheean’s case, someone at the top was anxious to avoid attracting attention to the fact the Armidale was sent unwisely into a very dangerous situation from which it was unlikely to escape. The young sailor’s impossibly brave battle is depicted in a painting in the Australian War Memorial.

And despite such contradictions, the navy has a long memory and has looked after its own by naming its Collins-class submarines after its heroes.

HMAS Sheean is the first Australian naval vessel named after an ordinary seaman rather than an officer.

This week, on the 78th anniversary of Teddy Sheean’s death, his belated VC was presented to members of his family.

War being such a chaotic and arbitrary process, there are other rich examples of very similar acts of heroism being treated in wildly different ways.

One was that of Lieutenant Commander Robert Rankin, captain of the sloop HMAS Yarra, who was escorting a small convoy of merchant ships in February 1942 when they encountered three Japanese cruisers and two destroyers.

Rankin ordered the convoy to scatter, poured out a smoke screen and turned towards the enemy fleet in a suicidally courageous bid to protect his charges.

He died in the attempt and has long been considered a prime candidate for a retrospective VC. His situation was remarkably similar to that of Captain Edward Fegan, commander of the British armed merchant cruiser Jervis Bay, which was basically a big and thin-skinned passenger liner fitted with a few outdated guns.

The Jervis Bay was escorting a convoy in the mid-Atlantic when the German pocket battleship Admiral Scheer attacked. Fegan ordered the convoy to disperse and then headed flat out for the Germans with heroic but inevitable results.

He was posthumously awarded the Victoria Cross.

One problem with acts of heroism by sailors is often the lack of witnesses to pass on recommendations for medals, but ways have been found to get around those strict requirements on occasions.

The shortage of Allied witnesses did not stop the British awarding a well-deserved VC to Gerard Roope, captain of the destroyer Glowworm. On a stormy day in April 1940, the Glowworm encountered the much more powerful German heavy cruiser Admiral Hipper. After a short, unequal battle, famously photographed from the Hipper’s bridge, the Glowworm rammed the German vessel slashing a large gash in its side.

The Hipper rescued 39 British survivors, and the German captain, Hellmuth Heye, wrote to British authorities via the Red Cross describing the courage of Lieutenant Commander Roope.

Roope, who died when his ship sank, was awarded the VC.

It could easily be argued that many others—the millions of soldiers who went ‘over the top’ into the fire of massed machine-guns and in the face of almost certain death, the airmen who climbed into bombers and flew endless raids over Germany with the odds stacked against them, all the unsung heroes who died heroically out of sight of their own side, deserve medals.

Like those who fought back in the dreadful burning shambles that was the dying HMAS Sydney after it was blasted by the German raider Kormoran off Western Australia. German survivors described how their own ship was fatally damaged by accurate fire from the Sydney’s X-turret before the turret was destroyed and the Australian warship sank with all hands.

The sad truth is that the unsung heroes are far too many in number for true justice ever to be done.