In two weeks’ time, ASPI’s annual Cost of Defence will hit the streets, detailing the ins and outs of the 2014 Defence budget. For those who can’t wait, here’s a preliminary analysis of the key points.

In two weeks’ time, ASPI’s annual Cost of Defence will hit the streets, detailing the ins and outs of the 2014 Defence budget. For those who can’t wait, here’s a preliminary analysis of the key points.

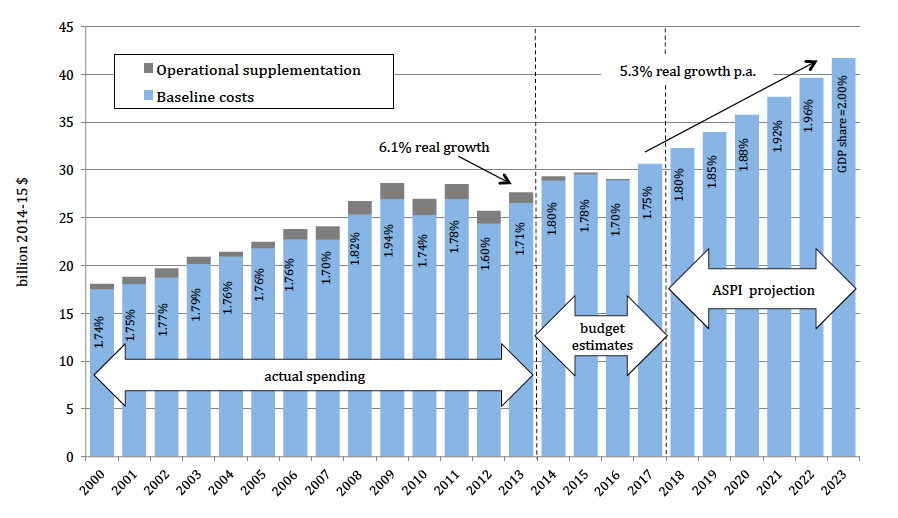

In the current fiscal environment, it was a surprisingly good budget for Defence. Spending will rise to $29.3 billion next financial year, a nominal increase of $2.3 billion on what was spent this year and a real (corrected for inflation) increase of 6.1%. As a share of GDP, defence spending will rise from 1.7% this financial year to 1.8% next year.

The key initiatives in this year’s defence budget was the reprogramming of $2 billion from 2017–18 which resulted in an additional $500 million this year (2013–14) and an additional $300 million, $550 million and $150 million respectively across the next three years. Yes, that’s right; despite the government’s fiscal consolidation, Defence will get extra money four years in a row.

On the savings front, there’s $1.2 billion to be saved over the next four years from ‘back office’ reforms, all of which will be available for reinvestment in capability—ie Defence will retain the money generated. Consistent with this, the number of civilians employed will fall from 20,900 today to 18,600 in four years’ time.

Over the next three years, defence spending is slated to remain largely static in real terms before rising to $30.6 billion in 2017–18. Beyond that, we don’t have visibility of what’s planned. But for the government to make good on its promise to boost defence spending to 2% of GDP by 2023–24, they would need to increase defence spending by around 5.3% every year for the six years following the forward estimates period.

On past experience, a sustained 5.3% rate of growth will be challenging to achieve. During the 2000s, when defence spending was growing at around 3% a year, Defence and defence industry had trouble absorbing the increase—to the extent that substantial sums of money were handed back. However, this time, there are 3–4 years available to prepare for the ramp-up so we can perhaps be more optimistic. Moreover, there’s nothing to stop the government from using future budgets to ease the task by commencing growth towards 2% of GDP prior to 2017–18. Indeed, one of the critical decisions for the forthcoming white paper will be the funding envelope from 2015 onwards.

A potential complication is that the government plans to return the Commonwealth to surplus around 2018–19, just after it looks as though defence spending will take off. If the government’s fiscal projections turn out to be overly optimistic, there’ll be pressure for further savings in order to preserve the surplus. If this happens, defence spending can’t expect to be immune.

Notwithstanding that risk, this year’s defence budget is about as good as it gets in an environment dominated by fiscal concerns. Not only has Defence received more money in the near term, but a credible path to 2% of GDP has been established.

Mark Thomson is senior analyst for defence economics at ASPI. Graph (c) ASPI 2014.