It’s been on the streets for a while now, but I’ve just got around to the Australian National Audit Office’s most recent annual review of Defence major projects. It’s a thoroughly useful compendium of data provided by the DMO, with an overview and critique from the ANAO.

There’s no headline story in the latest edition. As I noted last year, the data shows the project management benefits of military-off-the-shelf (MOTS) purchasing compared to development projects. In between those options there’s ‘Australianised MOTS’—modifying MOTS equipment to meet Australian requirements. The data set includes six development projects, 16 Australianised MOTS (AMOTS) and 8 MOTS. Consistent with previous observations that schedule is a bigger problem than cost, there’s little in the way of cost overrun in the portfolio of projects. But the schedule results speak for themselves:

| Schedule variation (%) | |

| MOTS | 7.4 |

| AMOTS | 34 |

| Developmental | 60.4 |

(Source: author’s analysis of data from ANAO and DMO)

The situation’s actually starker than those figures suggest. The MOTS average is made to look worse by delays in the introduction of a new heavyweight torpedo for the Collins class submarines. But that’s caused mostly by delays in establishing the full cycle docking program for the boats, rather than problems with the weapons. If we exclude that, the average MOTS schedule overrun is less than 3%. And the developmental project average is made to look better than it is by the ANAO’s (usually sensible) practice of taking second pass approval as the starting point. By that measure the F-35 Joint Strike Fighter is projected to be 2% ahead of schedule. But given that we’re already three years past the original planned in-service date and still five years from the initial operating capability, that seems a tad generous in this case.

In other places the auditors have presented a picture that’s formally accurate, but which has the potential to mislead. For example, the aggregated data on real cost variations—a useful measure of project performance—isn’t especially helpful. Ninety-six percent of the quoted total of $11 billion is the cost of the 58 additional F-35 aircraft approved last year. In DMO-speak that might’ve been a formal change of scope to the project, but it was always intended to happen.

Luckily, the data’s there to drill down into the individual projects. Otherwise I might’ve missed the surprising note that the AWD project had a downwards real cost variation last year… wait, what? Wasn’t the ANAO expecting a real cost increase in this project? It turns out that the variation’s due to a $110 million ‘transfer of funding for facilities construction to the Defence Support and Reform Group’. Remind me to add that back into any future cost quoted for the AWD program.

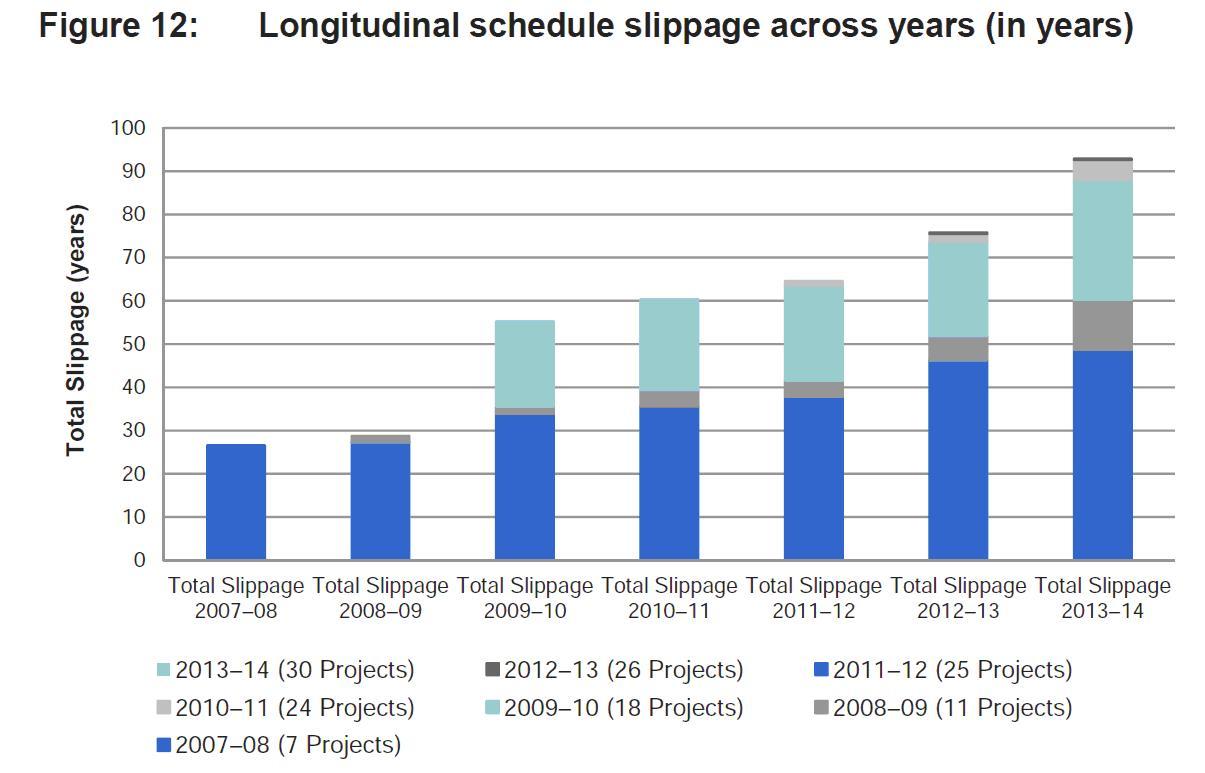

Cost and schedule problems have been around for as long as defence projects have existed. (I sometimes wonder if Noah’s ark was late and over budget. The movie certainly was, but Noah was at least dealing with a set of well-defined and unchanging specifications.) But there’ve been several attempts made to reform the Australian defence acquisition system, so it’s worth interrogating the data to see if the system is learning from experience, and whether the major changes that have been introduced post-Kinnaird are helping. ANAO have helpfully included some longitudinal data that helps us study the trends. Figure 12 (reproduced below) is probably the most helpful in this respect. It shows the total slippage (schedule overrun) of the current portfolio of projects over time.

Source: ANAO 2013–14 Major Projects report

ANAO interprets these and other data as showing that things have improved post-Kinnaird. They note that more than half the slippage in the projects they’re currently tracking is due to projects dating back to their 2007-08 report; since then they’ve added more projects to the mix, including some approved in prior years. ANAO note that ‘80% of the total schedule slippage … is made up of projects approved prior to the DMO’s demerger from the Department of Defence, in July 2005’. In other words, by this measure the pre-reform projects are the worst performers.

That’s reassuring as far as it goes, but I’d add a few caveats. First, in any set of projects that take a decade or more to deliver, you’d expect the older ones to be the worst performers—they’ve had longer to reach the point where slippage can no longer be avoided. Second, none of the projects in the initial set were MOTS: of the seven, three were development and four were AMOTS (and some of those were disguised development projects). Comparing their performance to later sets with MOTS projects included isn’t ‘apples with apples’. Finally, there’s the hard fact that the Kinnaird two-pass process has added substantially to the time taken to take a project from concept to approval. For the ADF, it doesn’t much matter where in the process the delay occurs—late capability is the result.

Andrew Davies is senior analyst for defence capability and director of research at ASPI.