The Australian Defence Force has performed valuable services in the 2019–20 bushfire emergency. More than 5,000 personnel have been involved in a wide range of tasks, both on the front line and in logistics and other supporting roles. There have been many accounts of the ADF bringing not just capability, but reassurance to communities threatened and impacted by bushfires.

With the growing consensus that such disasters will be the new normal, there will be much discussion and analysis, both in public and behind closed doors, about what the Department of Defence’s role should be in responding to them. Any discussion about roles will require discussion about funding. As the old saying goes, a dollar can only be spent once, so increasing the ADF’s capability to undertake domestic tasks will require either a reduction in other areas or additional funding—unless Defence can achieve the nirvana of developing dual-use capabilities that can perform both high-end warfighting and low-end support tasks equally well without additional cost. That has always been and will remain an elusive goal.

As those discussions ramp up, it’s helpful to consider what portion of Defence’s budget—and consequently its effort and capability—is already devoted to what it calls ‘national support tasks’.

It’s no secret that Defence doesn’t acquire capabilities dedicated to activities such as disaster relief; they’re not a ‘force structure determinant’, to use Defence’s term. But department has high-level strategic cover from the government for things like disaster response. Under the first of its three strategic defence objectives—‘A secure, resilient Australia, with secure northern approaches and proximate sea lines of communications’—the 2016 white paper states: ‘Our interest in a secure, resilient Australia also means an Australia resilient to unexpected shocks, whether natural or man-made, and strong enough to recover quickly when the unexpected happens.’ While the recent focus has been on the bushfire crisis (which was both natural and man-made), Defence has a long record of responding to other kinds of natural disasters at home and abroad.

Defence also acquires and sustains capabilities that are used by other agencies for tasks other than warfighting. For example, it provides patrol boats to the multi-agency Maritime Border Command to address civil maritime security threats. It also conducts services on behalf of the nation that are not entirely military. The Australian Hydrographic Office, a part of the department, is responsible for providing Australia’s national charting service, for example.

So it’s not quite correct to say that Defence solely prepares for war and only supports tasks other than warfighting on a ‘come as you are’ basis. But, generally, when it performs disaster response it is using capabilities acquired for other purposes.

Defence’s spending on actual operations performing ‘national support tasks’ in Australia is a very small part of its budget. The defence budget is divided into two main parts called outcomes. The bigger outcome by far is organisations that develop and sustain military capabilities. A much smaller part of the budget—roughly 2%—goes to the other outcome, which is using those capabilities on operations.

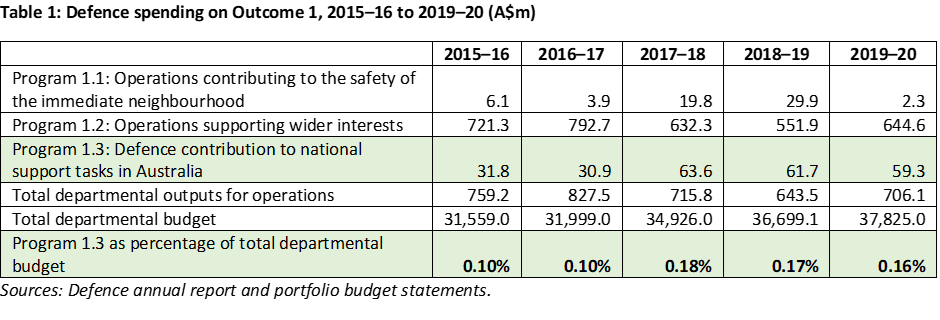

A small piece of that smaller part is for the Defence contribution to national support tasks in Australia. Over the past five years, the contribution has been under 0.2% of the total budget, highlighted in table 1 (although it will likely be bigger this year due to the bushfire emergency).* This includes contributions to border protection under Operation Resolute and support to major events such as the Commonwealth Games and ASEAN summits.

But Defence has a lot of potential capability it can supply if called on. Defence’s reporting doesn’t say how much of the much bigger outcome—namely, its organisations that develop and sustain capability, which include the three services—can be used for national support tasks. But we can get a rough idea by looking at the top 30 acquisition projects and top 30 sustainment products reported in the portfolio budget statements and annual report. The top 30s don’t include everything, but they cover the bulk of Defence’s capability spend.

Over the past six years, Defence has spent $59.2 billion between the top 30 acquisition projects ($34.3 billion) and top 30 sustainment products ($24.9 billion).

To drill down further, I’ve divided the projects and products into three categories (see here for the spreadsheets with all the detail):

- Category 1: Direct utility to national support tasks; frequent demonstrated use

- Category 2: Potential utility to national support tasks; some demonstrated use

- Category 3: Very limited or no utility to national support tasks; limited or no demonstrated use.

Category 3 is the biggest at a little over 60%, which isn’t surprising since it contains high-end, and therefore expensive, warfighting capabilities such as fighter planes, frigates, destroyers and submarines that are hard to put to use in national support tasks (noting that at times frigates have performed border protection—more on that later).

But category 1 at 17.4% is still a substantial $10.3 billion. That includes the kinds of capabilities we have seen hard at work during the recent crisis—trucks, utility helicopters and amphibious ships, as well as C-130J, C-27 and C-17 transport aircraft that can rapidly move supplies. It also includes capabilities like patrol and hydrographic vessels.

If we add to that category 2’s $13 billion, we get to $23.3 billion, or 40% of the total, having some utility. Category 2 includes capabilities that could be used in some circumstances, but it’s a long way from what they were originally acquired for, or serious overkill (like the use of P-8A maritime patrol aircraft with their sophisticated anti-submarine sensors and weapons to catch illegal fisherman and monitor bushfires).

I took a reasonably broad approach to the sorting, assuming that national support tasks included activities such as border protection. If we set a more narrowly focused task such as disaster response, categories 1 and 2 would be smaller and the 60/40 split would be more like 70/30.

Admittedly, it’s a subjective approach. Everyone would do it somewhat differently, but I suspect the results would likely be broadly similar.

These numbers do not include the cost of Defence’s people. Many national support tasks such as disaster response require lots of boots on the ground and are people intensive. The wage bill of an army engineer regiment, for example, hasn’t been factored in because there’s no public data on it.

With Defence spending only 0.2% of its annual budget actually performing national support tasks, that $23.3 billion appears to represent a lot of latent capability that could do more. Is it reasonable, then, for the public to expect, and the government to direct, that that $23.3 billion in capability be used more frequently in addressing emergencies like natural disasters? And is it reasonable to move the 60/40 force structure split closer towards 50/50 or beyond? I’ll look at that in the next part of this series.

* The defence portfolio additional estimates statements tabled on 13 February 2020 state that the Department of Defence received $87.9 million in additional government funding for Operation Bushfire Assist.