As Malaysians go to the polls tomorrow, 9 May, observers are holding their breath. Many unexpected turns have already taken place, few of which provide optimism or confidence in the political scene.

The return from retirement of Dr Mahathir Mohamad, the 92-year-old former prime minister for 22 years (1981–2003) was among the surprises of this race. Another was the announcement of a new anti-fake news law by the incumbent Prime Minister, Najib Razak, who has been in office since 2009. The law sparked controversy because it could allow a clampdown on media and free speech. Penalties include imprisonment for up to six years.

Najib has been linked to many corruption cases, including of misappropriating some US$700 million in public money from 1Malaysia Development Berhad (1MBD). The ‘anti-fake news bill’ doesn’t provide a clear definition of what would constitute ‘fake news’, but reportedly bans talking publicly about 1MBD without government approval.

The veteran ‘Dr M’—who once gained international prominence for his anti‑Western views and his popularisation of the ‘Asian values’ debate in the 1990s—warned that the upcoming elections will be ‘the dirtiest vote in history’. He’s unlikely to be right—not because the Malaysian election will be a model of transparency, but unfortunately because political transparency is increasingly rare in Southeast Asia.

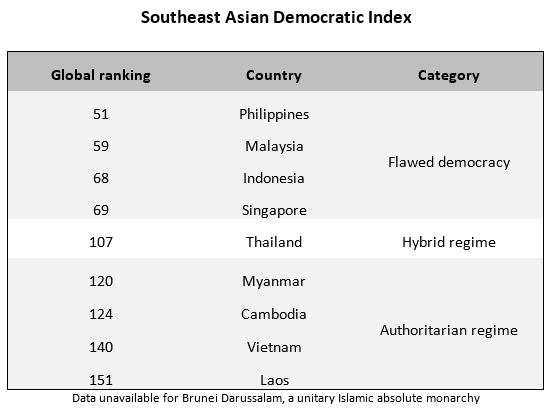

The Economist Intelligence Unit’s 2017 Democracy Index rates countries in five categories: ‘electoral process and pluralism; civil liberties; the functioning of government; political participation; and political culture’. It then classifies countries as ‘full democracies’, ‘flawed democracies’, ‘hybrid regimes’ or ‘authoritarian regimes’. Not a single country in Southeast Asia was rated a full democracy:

All indicators have shown a noticeable deterioration from the 2016 Democracy Index, when both Cambodia and Myanmar were ranked as hybrid regimes. This regression to authoritarianism (or autocratic tendencies) has been prompted by chronic problems, including political corruption, as well as weak electoral and justice systems. Other rankings, such as those measuring the progress of human rights or freedom of speech, reveal similar declines.

Notwithstanding the ever-debatable methodologies used to create the indexes, trying to understand the political mood in Southeast Asia is a daunting task, and any generalisation is risky. But critical reflections on the state of democratic regression cannot simply be labelled ‘Western’ narratives. They’re cause for concern among prominent regional thinkers too. The late Dr Surin Pitsuwan, a Thai diplomat and former ASEAN Secretary-General, noted that ‘democracy has not been very good in Southeast Asia’.

Rather, he suggested that it was a ‘misunderstanding of democracy’ that had brought about a generation of leaders—riding a wave of populism, corruption and patronage—who created a ‘charade’ of democracy. Moreover, there were too many expectations to be achieved in the short term. As a result, there has been a tendency to turn against democracy, giving rise to what former Indonesian President Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono called ‘a set-back of democracy’ last year at the Democracy in Southeast Asia conference organised by the Kofi Annan Foundation.

A popular explanation is that, historically, there has been a preference for strong rule and strongmen in Southeast Asia. This can be observed in the electoral results in Indonesia and the Philippines, as well as in the increasingly illiberal electoral practices in Cambodia. There, elections will take place in July, and Prime Minister Hun Sen has dissolved the main opposition party and clamped down on the press. Like everywhere else, rising inequality and lasting socio-ethnic (and in some cases, religious) tensions provide an opportunity for demagogic promises.

Moreover, there are rising new challenges and vulnerabilities—including cyber disruptions. Southeast Asian countries’ weak institutions and limited capabilities to monitor cyber activity increasingly expose them to more meddling. Even some mature democracies, well-off and with a wide array of institutional preparedness, aren’t immune to disruptive cyber threats. The use of automated fake Twitter accounts (bots) have been reported ahead of the Malaysian election. The results can be pernicious. The Democracy in Southeast Asia conference report noted:

Technology can complicate the conduct of elections because it is hard to audit or monitor. For this reason, it can easily generate public distrust of election results, which in turn may generate tension or violence.

The fragility of democracy in this region has been a long-term concern. The Southeast Asian political experience—despite its distinctiveness owing to its complex history and power relations—isn’t detached from global democratic ‘health’. The mood and global support for democracy some 20 years ago differed significantly from the environment today. That is true not only in Southeast Asia, but in the rest of the world.

Of 167 countries, the 2017 Democracy Index categorised only 19 as full democracies and 57 as flawed democracies. It categorised 39 as hybrid regimes and 52 as authoritarian regimes. In that light, Southeast Asia’s statistics don’t differ significantly from the global norm.

From Budapest to Washington, nations struggle to strike a balance between supporting lasting liberal values and winning elections. Yet Southeast Asia’s considerable, and ‘collective’, swing back to authoritarianism attests to its greater vulnerability. Dan Slater, head of the Weiser Centre for Emerging Democracies, suggests the ‘flu of social and political illiberalism is circumnavigating the globe’. If so, Southeast Asia is in urgent need of a ‘super vaccine’, and one with lasting effect. After the elections this year in Malaysia and Cambodia, Indonesia and—one hopes—Thailand will hold elections in 2019, followed by Myanmar and Singapore in 2020.