In December last year, National Interest listed the world’s five greatest battleships, defined as the most iconic. Definitions matter. Less adventurous but maybe more easily defended, here’s a list of the five greatest metal battleships defined as having the most influential designs. A list of the five that were greatest in service would be different again.

Beginnings

Gloire (pictured above), France, 1860. The French navy had the incentive to invent the armoured battleship, because in the 19th century it was the challenger; the dominant Royal Navy had much less interest in revolution. The idea of armored ships had been floated for decades, but actual experience with floating batteries in the Crimean War proved it. France took the next step in building the armoured battleship Gloire. The English-language historiography of the warship skips quickly past the wooden-hulled Gloire to emphasize that the British response, the iron-hulled HMS Warrior, was utterly superior. And so it was. But the starting point for more than 500 battleships completed between 1860 and 1949 was Gloire.

Honourable mention: Warrior.

Refinement

Royal Sovereign (pictured below), Britain, 1892. For 30 years after Gloire, battleship design was a stream of confusion. New ideas came thick and fast. Most had merits. Many were quickly superseded. Then experimentation stopped with the Royal Sovereign Class. Those seven ships introduced no great innovation great except a valuable increase in size, but they combined the best ideas of three decades, notably a high freeboard and the barbette, a French idea for lowering the center of gravity of the main armament emplacement. HMS Royal Sovereign was so right that for 15 years most battleships followed its general design.

Honourable mentions to earlier ships that introduced lasting features into battleship design: Monarch, Britain (revolving protected armament); Devastation, Britain (fore and aft revolving armament and the elimination of sailing rig), Redoubtable, France (steel) and Amiral Duperre, France (barbettes).

Revolution

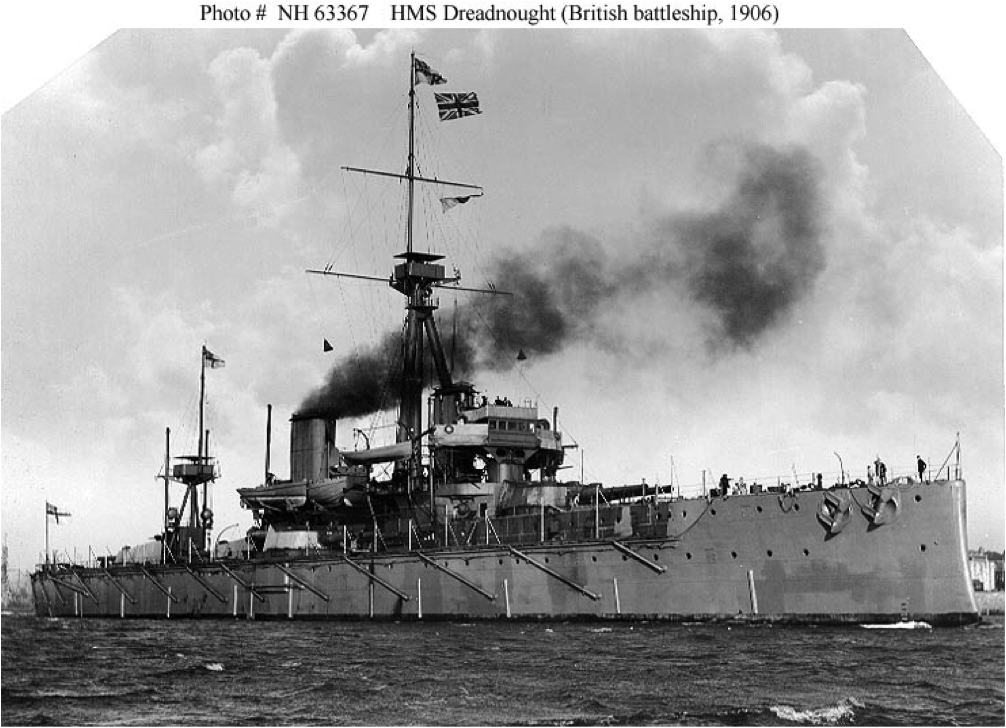

Dreadnought (pictured below), Britain, 1906. Soon after 1900, long-range gunnery looked increasingly practicable—and necessary, because torpedo ranges were rising, too. Dropping medium guns and adding big guns seemed wise. Major navies began drifting in this direction, especially the US Navy, which began building two ships, South Carolina and Michigan, with little armament but eight 305 mm guns. Then the energetic head of the Royal Navy, Sir John Fisher, turned the drift into a landslide. His HMS Dreadnought had 10 guns of 305 mm caliber and turbine machinery for a decisive increase in speed to 21 knots. The leap in propulsion efficiency meant that the ship displaced little more than predecessors it made obsolete. The world had little option but to follow.

Honorable mention: South Carolina.

Invincible, Britain, 1908. A curious fact in warship history is that Fisher did not want Dreadnought. Convinced that torpedoes fired by submarines and small ships could protect Britain, he wanted to replace the battleship with the armoured cruiser, a type that owed much to French development. Crucially, the Royal Navy had just invented network-centric warfare, as the historian Norman Friedman has recently pointed out. The Admiralty in London, unworried about home defense, could use radio to direct huge armoured cruisers across the planet, bringing them down on targets that it tracked on a plot of global naval movements. Fisher’s cruisers emerged as the Invincible Class, soon reclassified as battle cruisers in recognition of their closeness to battleships. They had battleship guns, high speed but only cruiser armour, because Fisher, wrongly, thought even battleship armour could not resist a new type of shell. Invincible launched a wave of battle cruiser construction, but Germany quickly realised that it should thicken the armour in its quite superior Von der Tann, making sacrifices elsewhere.

Honourable mention: Von der Tann.

The Final Phase

Hood, Britain, 1920. Two lines of development led to the last battleships, the fast battleships of WWII. One line ran from Dreadnought through several British and Japanese classes to the Italian Littorio, laid down in 1934. But by then the other line had already arrived. It ran from Invincible through the German battle cruisers to HMS Hood, an enormous battle cruiser that was protected as a battleship and was therefore really a fast battleship. That capability was achieved mainly through sheer size but also the innovation of heavily sloped side armour. Most subsequent battleships, of similar displacement, were comparable to Hood, but with improvements in detail.

Honourable mentions: Dante Alhgiheri, Italy (triple turrets) Queen Elizabeth, Britain (oil firing, higher speed); Nevada, USA (oil firing, reversion to all-or-nothing armour).

Postscript

None of the famous WWII fast battleships ranks as one of the five greatest designs. They were the end of the line, so none was influential. These ships were much better than predecessors, but they share that honour, since most were designed before the first was completed. And great advances were only to be expected, because of the treaty-imposed building holiday since 1922. Italy’s Littorio, very much an updated Hood, was the first of these ships but the US South Dakota and French Richelieu designs were the most efficient. Had battleships been built beyond the 1940s, the Japanese Yamato might well have been most influential, because it was so big.

The choice of four British ships among the five greatest reflects not bias in selection but bias in the data: Britain built about a third of all battleships and was especially dominant numerically and technically during the period of fast evolution. Moreover, a disruptive random factor, Fisher, accounts for two of the designs—even in the battleship world, individuals matter..

Bradley Perrett is Asia-Pacific bureau chief for Aviation Week & Space Technology. Images courtesy of Wikipedia (Gloire and Royal Sovereign) and United States Navy (Dreadnought). This is an updated version of the post.