On 23 April, Timor-Leste notified Australia that it had initiated arbitration under the 2002 Timor Sea Treaty of a dispute related to the 2006 Treaty on Certain Maritime Arrangements in the Timor Sea (CMATS). I’ve written a short piece on this elsewhere, but here I provide more context about this development.

The arbitration relates to the validity of the CMATS treaty. Timor-Leste argues that CMATS is invalid because it alleges that Australia didn’t conduct the treaty negotiations in 2004 in good faith by engaging in espionage.

The Timor Sea Treaty concluded between Australia and East Timor in 2002 (Annex B) provides for a three-person arbitral tribunal to settle disputes. A tribunal would consider whether it has jurisdiction to resolve this dispute. Assuming it did, then the tribunal would then judge the merits of Timor-Leste’s claim.

Treaties can be rendered invalid for a variety of reasons (PDF, Articles 46–53), such as restrictions on authority to express the consent of a state, error, fraud, corruption of a state, or coercion.

Alfredo Pires, Timor-Leste’s Natural Resources Minister has said that ‘during the process of negotiations, there were some exercises of covert operations’ which ‘assisted the inquisition itself during the process of negotiations’.

Australian Foreign Minister Carr and Attorney-General Dreyfus have stated that:

These allegations are not new and it has been the position of successive Australian Governments not to confirm or deny such allegations. However, Australia has always conducted itself in a professional manner in diplomatic negotiations and conducted the CMATS treaty negotiations in good faith. …the Australian Government is considering its response to Timor-Leste’s arbitration notification.

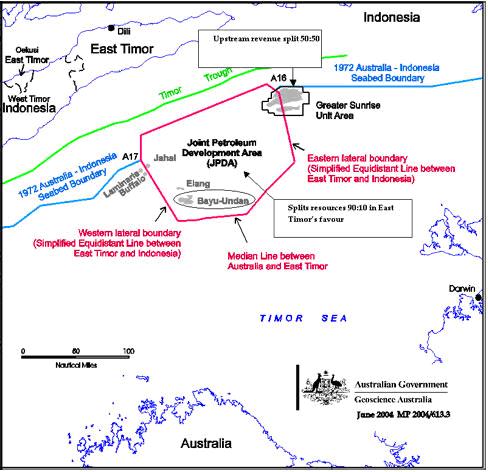

There was considerable speculation earlier this year that Timor–Leste would walk away from the treaty. CMATS entered into force in 2007 to cover the 80% of the Greater Sunrise field in the Timor Sea. (20% of the Greater Sunrise Unit area is in the Joint Petroleum Development Area.)

CMATS is an interim agreement; it doesn’t finalise maritime boundaries. It’s an example of the sort of provisional arrangements of a practical nature which the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea provides for.

CMATS is an interim agreement; it doesn’t finalise maritime boundaries. It’s an example of the sort of provisional arrangements of a practical nature which the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea provides for.

CMATS states that neither Australia nor Timor-Leste will assert claims to sovereign rights and jurisdiction and maritime boundaries for the period of the treaty (fifty years). The Treaty divides the revenue derived from resource extraction in the Greater Sunrise oil and gas field equally between Timor-Leste and Australia.

CMATS provides that if no development plan is agreed to within six years from when the treaty entered into force (23 Feb, 2007), then either country can give notice to terminate the treaty. This would take effect three months from when notice is given. The relevant date where there was an option of termination was 23 February this year.

So, given there isn’t an agreed development plan for Sunrise, termination is now a live option, where either side could give three months notice. But neither party has exercised that option. The treaty continues, even after Timor-Leste’s initiation of arbitration last month.

There’s a strong view in Timor-Leste that the processing plant for the Greater Sunrise field should be located on Timorese soil to spur its economy, rather than constructed as a floating plant. Onshore processing is part of Timor-Leste’s national strategic development plan. It’s also a political issue in the country, and featured in last year’s election campaign.

But a pipeline across the Timor Trench to an onshore LNG processing facility in Timor-Leste is both technically difficult and much more costly than a floating platform. Australia’s view (PDF, pages 512-513) is that it simply favours developing Sunrise to the best commercial advantage, including elements that would contribute to Timor-Leste’s development.

Under CMATS, a Maritime Commission is supposed to meet once a year and consult on maritime security generally. But it has never met, despite our common maritime interest in areas such as customs and unregulated fishing (chapter 5). And the first meeting isn’t not going to happen any time soon given Timor-Leste’s decision to pursue arbitration.

Timor-Leste has still got the option of cancelling the treaty, but feels that course might be legally messy: it might risk other joint development arrangements in the Timor Sea and wouldn’t provide certainty to business. Dili feels it’s better to secure a decision that the treaty in effect never really existed. If that was the result, it’d create the possibility of Timor-Leste opening negotiations on permanent maritime boundaries.

The arbitral tribunal would establish its own procedures. But proving espionage will be a difficult evidentiary requirement. Australia could decide not to participate. But a tribunal could still be formed by Timor-Leste asking the President of the International Court of Justice to appoint an adjudicator. The tribunal could make a ruling (Annex B (c)) even if Australia defaults. It also wouldn’t exactly be a great public relations success for Australia if we decided not to participate.

The arbitration initiative is a very high risk play for Timor-Leste. The trend of offshore technology is away from Timor-Leste’s objective of a pipeline to its country. Gas prices have come down in recent years, and shale gas is creating interest worldwide. Invalidating the treaty won’t provide an incentive to develop the Sunrise area. It’s more likely to result in the development languishing in the ‘too hard’ basket.

Anthony Bergin is deputy director of ASPI. Map courtesy of Australian Government Department of Resources, Energy and Tourism.