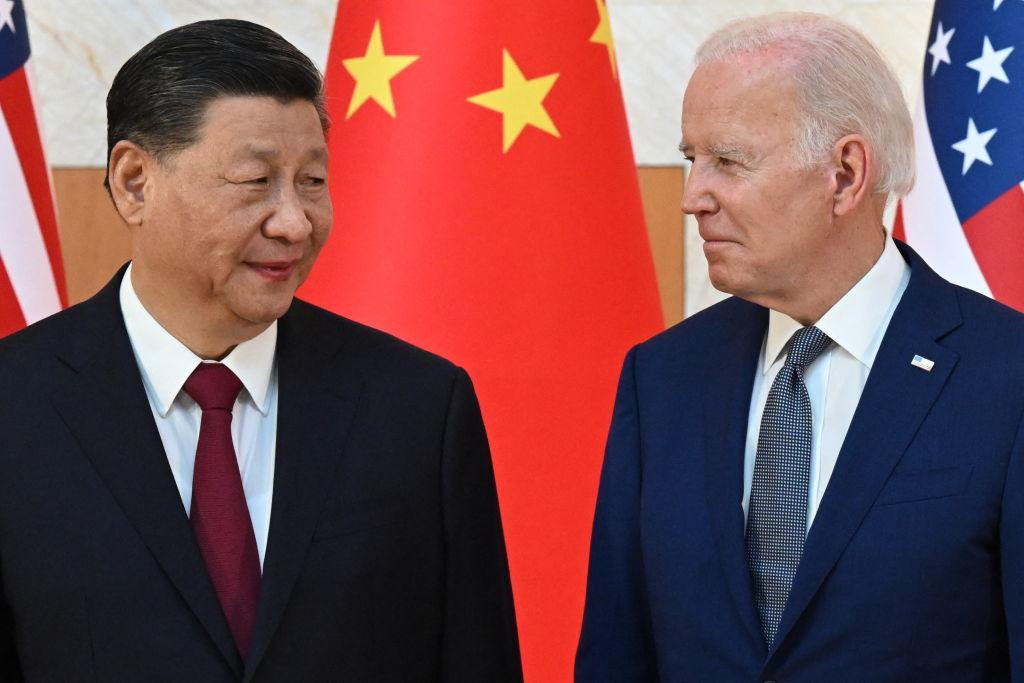

When US President Joe Biden and his Chinese counterpart, Xi Jinping, met in Bali last November, they agreed to hold high-level meetings to establish ‘guardrails’ for the Sino-American strategic competition. US Secretary of State Antony Blinken was scheduled to visit Beijing to inaugurate that effort last month. But when China sent a surveillance balloon (visible to the naked eye) over American territory, Blinken’s visit was shot down even faster than the balloon.

Though this certainly wasn’t the first time China deployed a balloon in such a fashion, the poor timing was remarkable. Still, it might have been better if Blinken had followed through with his visit.

Yes, China claimed, dubiously, that the device was a weather balloon that had gone astray. But intelligence cover-ups are hardly unique to China. Last month’s incident had echoes of 1960, when US President Dwight Eisenhower and Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev were scheduled to meet to establish Cold War guardrails. But then the Soviets shot down an American spy plane that Eisenhower initially tried to dismiss as an errant weather flight. The summit was cancelled, and real guardrails were not discussed until after the 1962 Cuban missile crisis.

Some analysts liken the current US–China relationship to the Cold War, since it, too, is becoming a prolonged strategic competition. But the analogy can be misleading. During the Cold War, there was almost no trade or talks between the US and the Soviet Union, nor was there ecological interdependence on issues like climate change or pandemics. The situation with China is almost the opposite. Any US strategy of containment will be limited by the fact that China is the major trading partner to far more countries than the US is.

But the fact that the Cold War analogy is counterproductive as a strategy doesn’t rule out the possibility of a new cold war. We could still go down that path by accident. The appropriate historical analogy for the current moment therefore is not 1945 but 1914, when all the great powers expected a short Third Balkan War, only to end up with World War I, which lasted four years and destroyed four empires.

Political leaders in the early 1910s didn’t pay enough attention to the growing strength of nationalism. Today, policymakers would do well not to repeat the mistake. They must remain alert to the implications of rising nationalism in China, populist nationalism in the United States, and the dangerous interplay between these two forces. Given the clumsiness of China’s diplomacy and the longer history of standoffs and incidents over Taiwan, the prospects for an inadvertent escalation should worry us all.

China regards Taiwan as a renegade province. Ever since President Richard Nixon’s visit to China in 1971, US policy has been designed to deter both Taiwan’s declaration of de jure independence and China’s use of force to bring about reunification. But now, some analysts argue that the double-deterrence policy is outdated, on the grounds that China’s growing military power may tempt it to strike now while it has the chance.

Other analysts are sceptical. They warn that an outright US security guarantee for Taiwan would provoke China to act, rather than deter it, and they worry that high-level official visits to the island are inconsistent with the ‘one-China policy’ that America has proclaimed since the 1970s.

Even if China eschews a full-scale invasion and merely tries to coerce Taiwan with a blockade, or by taking an offshore island, a single ship or aircraft collision in which lives are lost could be enough to trigger a broader escalation. If the US were to react by freezing Chinese assets or invoking the Trading with the Enemy Act, for example, the two countries could slip quickly into a real cold war—or even a hot one.

A recent war game staged by the Center for Strategic and International Studies in Washington DC suggests that the US might win such a contest, but at an enormous cost to both sides (and to the world economy). The best solution to the Taiwan issue therefore is to prolong the status quo.

Former Australian Prime Minister Kevin Rudd has argued that the West’s objective should not be to achieve a total victory over China, but rather to manage the competition with it. The sound strategy, he says, is to avoid demonising China and instead frame the relationship in terms of ‘competitive coexistence’. If China changes for the better in the long term, that will simply be an unexpected bonus for a strategy that aims to manage great-power relations in an era of traditional as well as economic and ecological interdependencies.

A good strategy must rest on a careful net assessment. Whereas underestimation breeds complacency, overestimation creates fear—either of which can lead to miscalculation. China has become the second-largest national economy in the world, but even if its GDP seems on track to exceed America’s someday, its per capita income is still less than a quarter that of the US, and it faces a number of economic, demographic and political headwinds.

Not only did China’s working-age population already peak in 2015, but its economic productivity growth has been slowing, and it has few committed political allies. If the US, Japan and Europe coordinate their policies, they will still represent the largest part of the world economy, and they will retain the capacity to organise a rules-based international order that can help shape Chinese behaviour. These longstanding alliances are the key to managing China’s rise.

In the near term, given Xi’s increasingly assertive policies—including foolish acts such as the ill-timed balloon—we will probably have to spend more time on the rivalry side of the equation. But if we maintain our alliances and avoid ideological demonisation and misleading Cold War analogies, we can succeed.

If the Sino-American relationship was a card game, one could say that we have been dealt a good hand. But even a good hand can lose if it’s badly played. Seen against the historical context of 1914, the recent balloon incident should remind us why we need guardrails.