It is difficult to imagine the world without Henry Kissinger, not simply because he lived to be 100 years old, but because he occupied an influential—and sometimes dominant—place in American foreign policy and international relations for more than half a century.

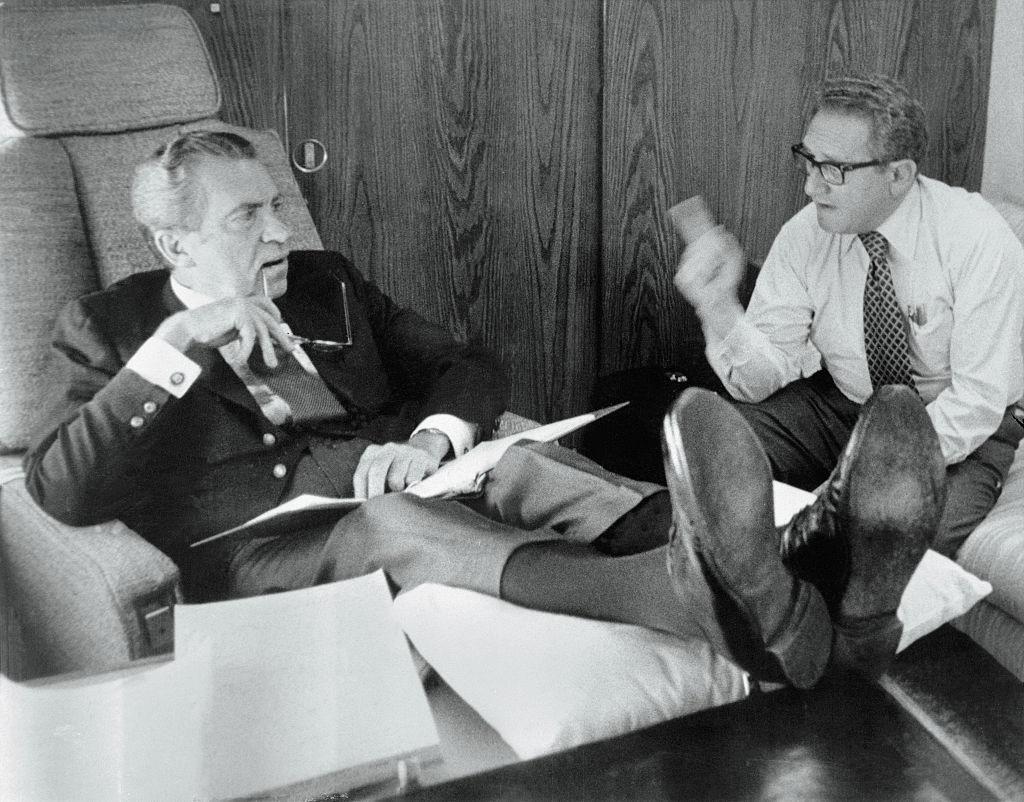

Born in Germany in 1923, Kissinger immigrated to the United States in 1938, returned to Germany while in the US army, and then was a student and later a faculty member at Harvard University. He served for eight years in the US government, first as national security adviser and then as secretary of state (holding both roles simultaneously between 1973 and 1975) under Presidents Richard Nixon and Gerald Ford.

His accomplishments in office were many and substantial. For starters, there was the opening to China, an opportunity created by the Sino-Soviet split, but discerned and then exploited by Kissinger and Nixon to exert leverage over the Soviet Union (America’s principal adversary at the time). That diplomatic overture not only ended decades of hostility between the US and China. It also produced a formula for finessing differences over Taiwan, laid the foundation for China’s economic transformation and established an enduring and ever-more important relationship.

There was also détente: the relaxation of tensions with the Soviet Union. Kissinger and Nixon (their close rapport is one explanation for Kissinger’s influence) structured the relationship between the era’s two superpowers. That allowed for nuclear-arms control talks, rules of the road for managing conflicts involving their respective allies, and regular summitry—all of which helped keep the Cold War cold when it could have turned hot or, worse, led to nuclear escalation.

Then there was the Middle East. The parallels to today are striking, since it was exactly 50 years ago that Egypt and Syria caught Israel off guard with a surprise attack, just as Hamas did on 7 October. Kissinger and Nixon made sure that Israel had the military support it needed; but they also pressured the Israelis not to overuse military force, as that could pull the Soviet Union into the war or eliminate the prospects for diplomacy in its aftermath. Kissinger’s personal shuttle diplomacy helped bring about a ceasefire and a separation of opposing armed forces, setting the stage for the Egyptian-Israeli peace accord negotiated by President Jimmy Carter.

These accomplishments, any one of which would constitute a significant legacy for a secretary of state, demonstrate many of the elements central to Kissinger’s approach to world affairs. He embraced diplomacy, to be sure; but it was a diplomacy that operated against the backdrop of a favorable balance of power. It was not just diplomacy, but diplomacy with restraint.

Kissinger had a conservative bent. He prioritised order, which meant that his efforts to avoid war took precedence over the more ambitious goals being advanced by others who wanted to transform countries or impose peace with justice. His emphasis was squarely on relations between countries more than on the politics within them. As he saw it, the principal business of US foreign policy was to shape the foreign policy of others.

One finds these themes in his many books and articles, from his doctoral dissertation and his memoirs to his reflections on nuclear weapons, alliances, diplomacy and—more recently—world order, China and artificial intelligence. Even if Kissinger had never served in government, he still would have exerted a profound influence on US foreign policy through the power of his ideas and the eloquence of his writing.

Of course, there have been other great modern US secretaries of state, such as George Marshall, Dean Acheson and James Baker. But none compared with Kissinger when it came to being both an actor and an analyst. He was the preeminent scholar-practitioner of his era.

But this is not to suggest that Kissinger did not get some things wrong. He most certainly did, as his many detractors and critics are quick to point out.

The most controversial policies that he was associated with involved the war in Vietnam. Critics of the war blame Kissinger for prolonging it, and for expanding it into Cambodia, at a time when many judged it to be both unwinnable and not worth fighting. But he also drew fire from supporters of the war, owing to his role in negotiating an end to it. The terms of the ‘peace’ allowed North Vietnam to achieve its victory over the South within two years.

Kissinger also played a controversial role in the events of 1971, when he stood by Pakistan (a US ally that had helped midwife the breakthrough with China) despite reports that its government was carrying out a massive campaign of repression, or what many judged to be a genocide, in what is now Bangladesh. Finally, Kissinger still draws intense criticism for his role in trying to topple Salvador Allende’s democratically elected government in Chile, owing to its ideological leanings.

Kissinger would occasionally try to rebut these and other complaints about his policies. But his efforts were not totally convincing, because some of the main critiques did have merit. The larger point, though, is that his accomplishments were great, and far greater than his failures.

The result is a lasting, worthy legacy of seriousness about the world and about the danger of a US foreign policy defined by either underreach (isolationism) or overreach (trying to transform situations or regimes that can be only managed, at best). It is a legacy Americans would be wise to heed as they once again face a world marked by great-power politics and growing disarray.