Italian Prime Minister Mario Draghi and French President Emmanuel Macron are on track to sign a bilateral accord—named the Quirinale Treaty after the Roman palace—designed to boost their countries’ industrial and strategic cooperation. But this new Paris–Rome power axis may do much more than that as it may very well alter the leadership dynamic within the entire European Union.

This emerging Draghi–Macron alliance may seem like an odd pairing, because some French look down their noses at Italians. I personally witnessed quite a lot of this when I lived in Aix-en-Provence, a place where the French and Italian cultures often compete and clash. But judging the Italians harshly for their politics is much harder to do now that the supremely competent and experienced Draghi is in charge.

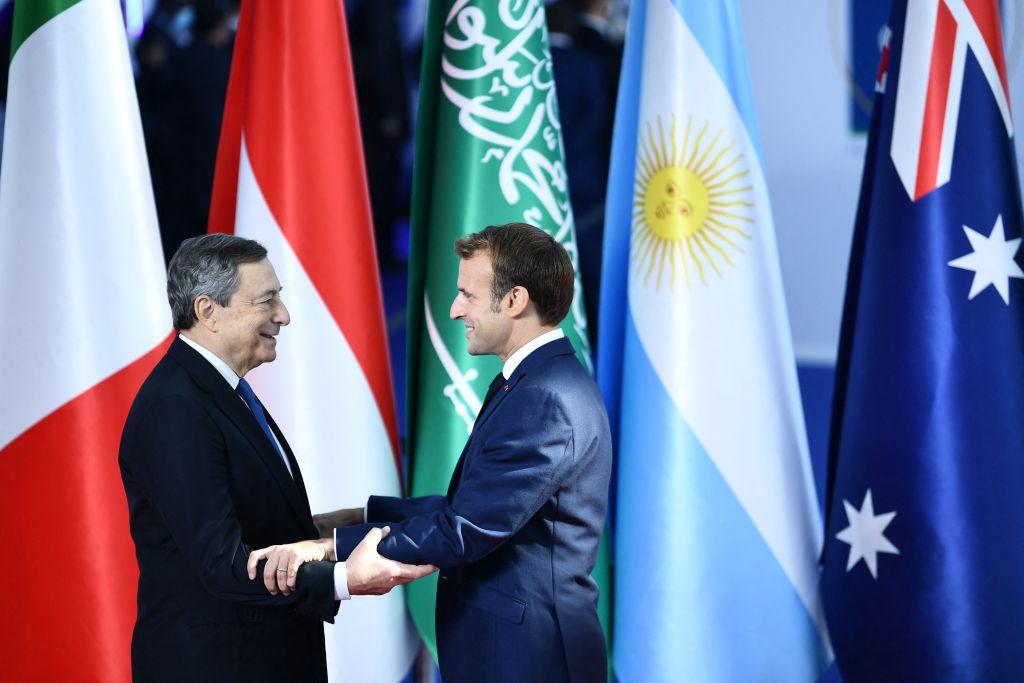

A mere 10 months after taking office, Draghi has emerged as one of Europe’s most highly regarded and influential politicians. Just before last month’s G20 summit in Rome, he held a private meeting with US President Joe Biden—a tête-à-tête that testifies to his elevated standing in the transatlantic alliance. According to the New York Times, Biden made clear that ‘Italy and the United States needed to show that democracies can function successfully and that Mr. Draghi was doing that.’

But Draghi is not only showing the world that Italy can function like other rich, modern countries. The staunchly pro-European, pro-American and pro-NATO prime minister has also made savvy political moves that could change the face of Europe and the EU. For starters, he has forged a deep bond with Macron. Working together, the two leaders have an excellent opportunity to wield more influence over EU policy—from the economy to defence—now that Angela Merkel is stepping down as German chancellor after 16 years in power. The Quirinale Treaty is a concrete result of their new cooperation to fill the gap created by Merkel’s departure.

If they succeed, the locus of influence in the EU will shift southward—and towards greater European integration. Here, Draghi and Macron see eye to eye, including on the critical issue of European defence. Both are confident in the EU’s ability to act independently as a military force while still maintaining its full commitment to NATO.

Biden himself appears to accept this view. According to the Times, ‘Mr. Biden told Mr. Draghi [during their October meeting] that he viewed a strong European Union—even one with a unified military defence—as in the interest of the United States.’ Given America’s growing focus on the Asia–Pacific theatre, a unified European defence capability is exactly what the US needs.

With China becoming increasingly belligerent under President Xi Jinping, a European defence force could fill in the strategic gaps created by NATO’s own efforts to reorient itself towards Asia. It is wrong to argue that America is turning its back on Europe with its pivot to Asia. Supporting greater military independence for Europe means that NATO will be freed up to focus on China, which poses as much of a military threat to Europe as it does to the US.

In any case, the Biden administration’s tacit support for a unified European defence force will give Draghi and Macron additional ammunition to promote the idea. Given the possibility of strong opposition from Germany and some Central European countries, it is hardly a fait accompli.

Adding to the potential of the Draghi–Macron alignment is the fact that the incoming German government may be far more sympathetic to their worldview than Merkel ever was. Instead of ‘Frau Nein’ objecting to most initiatives designed to deepen EU integration, they will encounter a genial ‘Herr Maybe’ in her successor. Although the new chancellor, Olaf Scholz of the Social Democrats, will need to be convinced of the benefits of change, particularly deeper integration, he will not immediately reject new ideas out of hand, as has mostly been the case for the past 16 years under Merkel. Scholz will also be working with coalition partners who are much more open to integration (though the Free Democrats remain sceptical of greater financial integration).

A three-party German coalition government comprising the Social Democrats, the Greens and the Free Democrats could turn out to be a boon for the European project, and not only with respect to defence policy. On issues ranging from fiscal and monetary union to eurobonds, China, and Russia, Draghi and Macron will no longer be banging their heads against a closed door.

A significant acceleration of European integration may well be in the cards. Such a development could not come soon enough, given Donald Trump’s possible return to the White House in 2025. Just the thought of that prospect should scare the daylights out of most Europeans, impelling ever-faster integration, whatever the obstacles. Who could blame them?