In opting to acquire nuclear-powered submarines as a part of the AUKUS deal with the United States and the United Kingdom, Prime Minister Anthony Albanese has committed Australia to a price tag of about $368 billion dollars. That’s a lot of money, even spread over several decades. It will result in the acquisition of an as yet uncertain number of submarines—possibly upwards of eight—as well as improvements to port and maintenance facilities, training and education of crews and the creation of a nuclear capable workforce and research capacity. As these boats retire—and since the first ones Australia is getting are second hand—that time is not as far off as one might think. Defence will need money to manage the nuclear waste with unknown technologies at a yet-to-be-decided location. Additionally, some money will go to American submarine builders to improve assembly lines.

The goal is to make Australia more secure. What needs to be examined is what security opportunities will be foregone because of the submarine project’s absorption of much taxpayer largesse and government political capital. Might not such expenditure on other things result in an equally, or even more, secure Australia? And would such expenditure not generate greater second-order effects, such as more quality jobs or a better way of life for all Australians?

In the enthusiasm for AUKUS, for example, the implementation of serious climate change policies has again been overlooked. This is telling because the threat to Australia’s security from climate change is only growing more severe. At a 20 March press conference, United Nations Secretary General Antόnio Guterres released the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change’s 6th synthesis report and again called on major greenhouse gas producing nations to make a serious effort to halt emissions to save humanity. He peppered his talk with expressions of frustration, such as ‘the climate time-bomb is ticking’, and we are ‘on thin ice’ and the ‘ice is melting fast’.

I suspect that the $368 billion earmarked for submarines would go a long way towards meaningfully reducing Australia’s emissions. This would smooth Australia’s transition to a future in which electricity, produced by renewable technologies, is the dominant energy source for all homes and industries nation-wide. Professor Saul Griffith, author of The Big Switch, argues that it’s now possible to electrify virtually all of the nation’s economy with existing technologies, largely eliminating Australia’s greenhouse gas emissions.

The move towards an electrified future would necessitate a government-led whole-of-nation investment program. It would be a nation building effort, much as the Snowy Mountains Scheme was, and as the nuclear-powered submarines would be. Of course, some workers will need to adjust. Those employed in the fossil fuel economy would find ready employment, with government provided retraining, in the installation of solar and wind farms or in the mining and processing of the new economy’s essential minerals such as lithium and rare earths.

Because of its vast space and plentiful sunlight and wind, Australia could also become a global energy powerhouse. Electricity that Australians do not need could power Indonesia, Papua New Guinea, Singapore and elsewhere, exported via undersea cables.

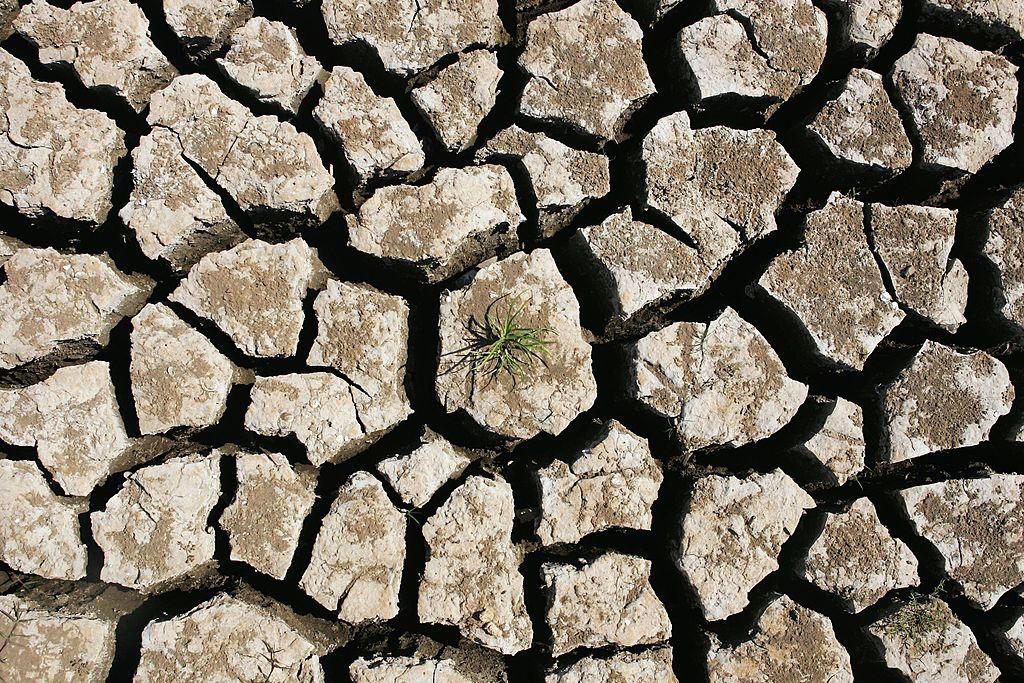

There’s no doubt that China is challenging the established US order. However, the reality is that because of a misunderstanding of risk, the enhanced security created by eliminating the burning of fossil fuels would be far greater for Australia than that gained from a militarised response to China’s challenge. China’s assertiveness, even under worse case scenarios, does not pose an existential risk to Australia. If the emission of greenhouse gases continues, on the other hand, Australia will experience worse and more frequent natural disasters, become increasingly arid and see major reductions in food production.

More worrying is the damage climate change will do to the stability of the broader region. Changes in rainfall patterns and rising seas will reduce food production in Asia and Oceania which will lead to rising social tensions, state disintegration, intra- and inter-state conflict, mass migration and the proliferation of ungoverned spaces. Under the rampant climate upheaval that will result if greenhouse gas emissions are not stopped, Australia will need to contend with a much more destabilised region posing a multitude of threats to its territory and interests—much in the manner of a more assertive China, just more chaotic, widespread, and closer.

A nation building program focused on electrification from renewable sources would also solve another major security risk Australia faces—the fragility of its liquid fuel supply. Australia is wholly dependent on the importation of crude and refined petroleum products. Much of Australia’s refined fuel comes from Asia: China met 13.5% of Australia’s needs in 2020. As a precaution against disruption of supply, Australia established a petroleum strategic reserve, but the product is sub-optimally located in the salt caverns of Texas and Louisiana and is not readily accessible.

A failure of liquid fuel supply would cascade rapidly through the economy. Trucks would come to a halt, mines would shut and industries cease to operate. Within weeks supermarkets would start to run out of food. The liquid fuel threat over Australia can be solved with leadership, resolve and money—perhaps part of the $368 billion. Relieved of its dependence on imported liquid fuels through electrification, Australia would be more secure.

Australia could further enhance its national security by increasing its investment in soft power. According to Andrew Bacevich, the US has a tendency to see international disputes as military problems and does not see benefit in seeking solutions through non-military means. For the US, the first tool with which to manage a dispute is war or its threat. This need not be the case for Australia. If Australia opens additional consulates across the region, significantly enlarges international engagement by all government departments, and establishes cultural, language and education programs, for example, an outcome is likely to be a better understanding of our neighbours, including China, which would create opportunities to deescalate conflict rather than the reverse.

National security cannot be achieved by the acquisition of any one weapon system, no matter how expensive, state-of-the-art or impressive. In committing to these submarines, Australia has shut out other options with no national debate. Their cost, barring a significant increase in the overall defence budget, will create an unbalanced defence force capable of operations in only narrowly prescribed scenarios. Other options would result in much better outcomes for the Australian people. The building of a nuclear-powered fleet carries risks of its own. Australia is an inexperienced operator and requires investment in technologies which this country has no track record in building or using. In contrast, our scientists, engineers and grid operators have been at the forefront of advances in solar and wind generation technology.

Australia needs a national discussion on what security means and how it can best be achieved. It needs the leadership to envisage alternate futures and the policies to see through a nation-building program that will result in a more self-reliant and regionally engaged nation. Then Australia will truly be secure.