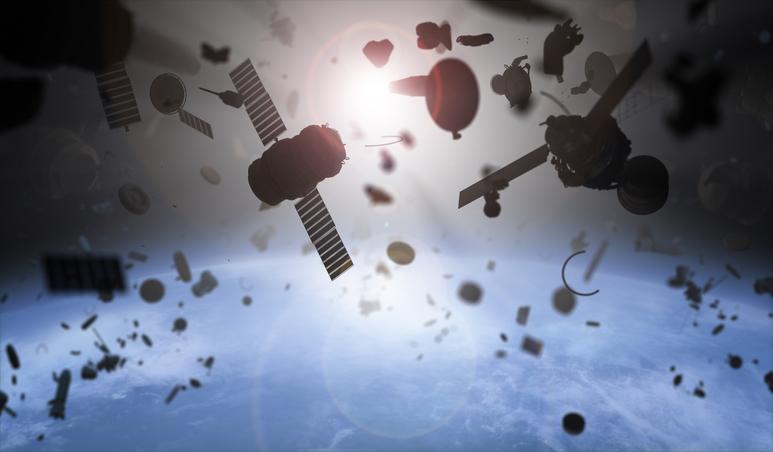

The Russian military’s test of a direct-ascent anti-satellite weapon against a defunct satellite has created a huge cloud of more than 1,500 trackable pieces of debris, which may pose a threat to spacecraft for decades.

The destruction of Cosmos 1408 on 15 November was confirmed by the US State Department and the US Department of Defense. Space debris-tracking company LeoLabs said that the blast likely generated hundreds of thousands of smaller pieces that can’t be tracked. Travelling at orbital velocity, even a small piece of debris can seriously damage a spacecraft.

The debris from the explosion posed an immediate threat to the International Space Station, and the danger of collisions will repeat every 90 minutes as the ISS, China’s Tiangong space station and many satellites pass through the expanding debris cloud. Secure World Foundation’s Brian Weeden declared that it was ‘beyond irresponsible for Russia to do this’.

Russia is the latest in a group of nations to demonstrate kinetic-kill anti-satellite weapons (ASATs) in a ‘live test’ that destroyed a target in orbit. China tested a kinetic-kill ASAT in January 2007 against a defunct weather satellite, producing a large cloud of debris, much of which remains in orbit.

In Operation Burnt Frost in October 2008, the US used a modified SM-3 interceptor missile to bring down a malfunctioning satellite and prevent an uncontrolled re-entry that could have dispersed toxic fuel over populated areas.

In 2019, India tested an ASAT against one of its own satellites, creating more long-lasting debris.

The Secure World Foundation’s unclassified report on global developments in counterspace weaponry states that Russia’s Nudol direct-ascent ASAT, the system most likely to have been used in this test, is a ground-based ballistic missile designed to intercept targets in low-earth orbit. The system has been tested at least 10 times, with numerous failures, and this is the first time it’s destroyed a target satellite. Like its US counterpart, the SM-3, which is normally based on naval vessels, the land-based Nudol is adapted from ballistic missile defence. Unlike the SM-3, the Nudol ASAT could be nuclear-armed under some circumstances.

In addition to the immediate dangers from space debris generated by the Russian test, it’s a huge setback to international efforts to prohibit kinetic-kill ASATs that physically destroy their targets. Those efforts are supported by Russia’s Roscosmos space agency and its head, Dmitry Rogozin. The test shows contempt for efforts through the United Nations to create new norms of responsible behaviour following the UK’s tabling of General Assembly resolution 75/36 in December 2020 and the planned establishment of an open-ended working group in 2022 to pursue responsible behaviour in space.

There should be added urgency in the space policy and arms control communities to increase efforts to agree on a ban on kinetic-kill ASAT testing and development. The Secure World Foundation has called on the US, Russia, China and India to declare unilateral moratoriums on further testing of ASATs that could create additional debris and to work with other countries towards solidifying an international ban on destructive ASAT testing.

But there’s a risk that an intensified security dilemma emerging from this test could torpedo efforts to achieve such a ban and weaken trust within the working group on space threats and responsible behaviour despite the need to make rapid progress.

The challenges are clear.

A ban on testing and deployment of kinetic-kill ASATs must be verifiable and enforceable. The fact that systems such as the Nudol and SM-3 are based on ballistic missile defence technologies complicates verification and monitoring of compliance. Would states such as Russia and China agree to intrusive inspections as an essential component of a verification and monitoring regime? How can dual-role systems, which can carry out both ballistic missile defence and ASAT tasks in low-earth orbit, be differentiated? A suspicion that states will maintain such capabilities will intensify pressure to develop counter-responses.

The proponents of a ban need to confront the reality that while their diplomatic efforts occur through international bodies such as the UN working group, the activities of states’ military forces may be disconnected from the objectives and statements of civil authorities or the good intentions of representatives at such negotiations.

It doesn’t seem credible that Roscosmos would have agreed to a test of a kinetic-kill ASAT that could then place the ISS, its own cosmonauts and US astronauts at risk. It must not have known that this test was going to take place, and almost certainly would have taken protective measures if it had been warned. The Washington Post quoted NASA administrator Bill Nelson as saying he believed the Russian space agency was not informed of the test by its own government.

There’s still the question of who should be held responsible if there’s to be a verifiable and meaningful ban on ASATs.

The Russian ASAT test is a huge setback to efforts to build international trust upon which any future ban on ASATs, let alone norms of responsible behaviour, could be based. In addition to blowing up a satellite and endangering the space environment, Russia has seriously damaged the prospects for meaningful progress in arms control in space. The fallout leaves serious questions as to whether the Russian government, which would have authorised this test, is genuine in promoting efforts towards arms control in space.