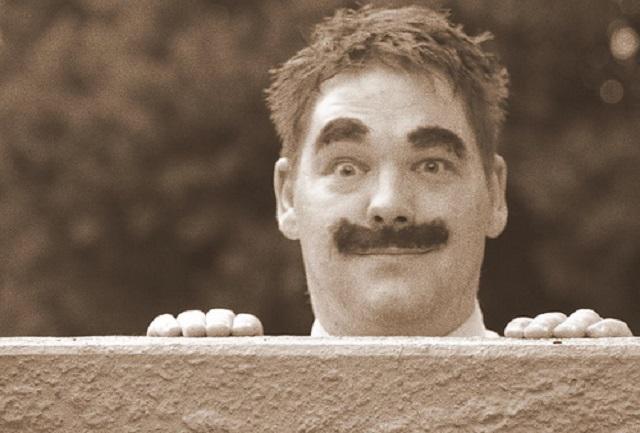

Groucho Marx got the conundrum into one great line: ‘I don’t want to belong to any club that would accept me as one of its members.’

My argument that Australia should join the Association of South East Asian Nations confronts Canberra’s wish to do a semi-Groucho: ‘Love the club. Think it’s a wonderful, vitally important club. But we’d never want to join.’

Excellent explanations of the semi-Groucho have been written by Rod Lyon and Matt Davies. And to pile it on, this column will further explore the case for the negative offered by official Canberra. To recap, the previous column boiled down Canberra’s semi-Groucho to this:

Base argument: ASEAN would say no.

Minor point: ASEAN membership would involve a lot of work for diplomats.

Major point: Australia would subordinate itself to ASEAN.

Base argument: If asked today, ASEAN would, indeed, say no. And Australia, on the semi-Groucho logic, would never ask. The purpose of this series, as laid out in the first post, is to argue that this is the starting point for a conversation that will take decades.

Much that is already happening in Asia will make this a necessary, even vital process of imagination, as much for ASEAN as for us.

Minor point: The ‘too much work’ argument is a laugh. Repurpose another Groucho line and move on: ‘Diplomacy is the art of looking for trouble, finding it everywhere, diagnosing it incorrectly and applying the wrong remedies’.

Major point: The subordinate-to-ASEAN line is interesting in what it claims about the reality of ASEAN workings today and the future of the ASEAN Community.

Neither the proclaimed theory nor the habits of ASEAN make this a knock-out blow in the case for the negative. ASEAN is a long way from becoming the European Economic Community, much less the European Union. We pay our diplomats to know the difference between Europe and Asia.

The subordinate-our-values line is significant. Matt Davies argues that ASEAN norms would be ‘a pre-emptive blanket that smothers the possibility of criticism from other member states. Australia joining ASEAN would have numerous deleterious consequences for the promotion of our values. What is the benefit of Australia being willingly mute in the realm of human rights and democracy?’

If accepted, this is a killer semi-Groucho. Here’s a rebuttal in several parts. First, Matt isn’t describing an Australia I recognise. His is an Australia that sits still, shuts up, goes along and doesn’t push. Not us. Australia would no more change its fundamental nature within ASEAN than Indonesia or Malaysia or the Philippines or Vietnam or any of the ten have changed their essential natures in the Association.

Further, on the long march to Community, ASEAN is seeking to remake its regionalism in important ways that Australia will happily embrace. The proclaimed norms are shifting—we’d be pushing with the tide.

In the values discussion, the Blueprint for the ASEAN Socio-Cultural Community commits to an ASEAN that will ‘promote human and social development, respect for fundamental freedoms, gender equality, the promotion and protection of human rights and the promotion of social justice.’

Not much in that to force Oz diplomats to sit down and shut up.

Australia has already had a big subordinate-ourselves-to-ASEAN argument that turned out, on inspection, to be a mouse that couldn’t squeak, much less roar.

To gain the seat at the East Asia Summit, Australia had to sign an ASEAN foundational document, the Treaty of Amity and Cooperation. Oh horror, went the subordination argument, Australia will have to compromise its commitment to the US alliance. This was tosh.

Australia signed the TAC while stating it had no impact on alliance commitments. ASEAN didn’t twitch and neither did the alliance. And into the EAS marched Oz. Joining ASEAN as an observer—the half in half out stage – Australia wouldn’t even need the clarifying letter we used with the TAC. We’d be joining for – and loudly boosting – the aims of the Community.

When I spoke to the former Foreign Minister, Bob Carr, he ran through the negative argument and came down finally to the problem of Australia reaching for ASEAN membership as a huge distraction.

‘The Department’s view was that this was not in our interest, that we had a foreign policy focus different from that of most of the other nations in ASEAN, and that we’d have to compromise some of our national interests if we sat as a member of ASEAN. There was an argument I don’t think the Department used that I would have used: that is it would have taken an enormous amount of diplomatic capital to have got us into the thing. And I think softer diplomacy in Southeast Asia reflects our national interest better—not the arm twisting and the lecturing and the hectoring that would have been involved in persuading ten nations to allow Australia in. The process of attempting to get in would have had them all thinking of the ways Australia is different from them. So, if I were Foreign Minister, and someone put to me that we should join ASEAN, I would have thought that it is a huge distraction—one that could have activated and agitated hostility or reservations at very least about Australia.’

In office, Carr stressed Australia’s acceptance of ASEAN’s centrality and the growing importance of ASEAN views, as part of Australia’s ‘more sophisticated understanding of our region and our place within it.’ In a speech in Singapore in 2013, the Foreign Minister praised ASEAN as integral to the political shifts in Asia towards democracy and freedom: ‘We’ve seen the achievement of ASEAN centrality at work and a shift from regional cooperation to regional integration. Australia listens and takes close note of what ASEAN and its member states think. And I highlight alignment with ASEAN as a feature of my period as Foreign Minister’.

A position of ‘alignment’ with ASEAN and its centrality would be a useful place for Australia to start a membership push.

What of a ten-year discussion—based on the ASEAN norms Australia has already embraced in the EAS and the ASEAN Regional Forum—working towards observer status, and not full membership?

Bob Carr told me he understands the approach, but it’s an idea to kick down the road for another time:

‘I’d say in the words that Willy Brandt used about East and West Germany coming together: “What belongs together will come together.” Let’s look at consultation in foreign policy terms—I quoted the example of us moving to a common ASEAN position on engagement with Myanmar Let’s look at a closer economic relationship and if in the longer term—over the next decade, decade and a half, two decades—another proposition emerges we can look at that.’

Time to reverse the semi-Groucho and start talking about the proposition.