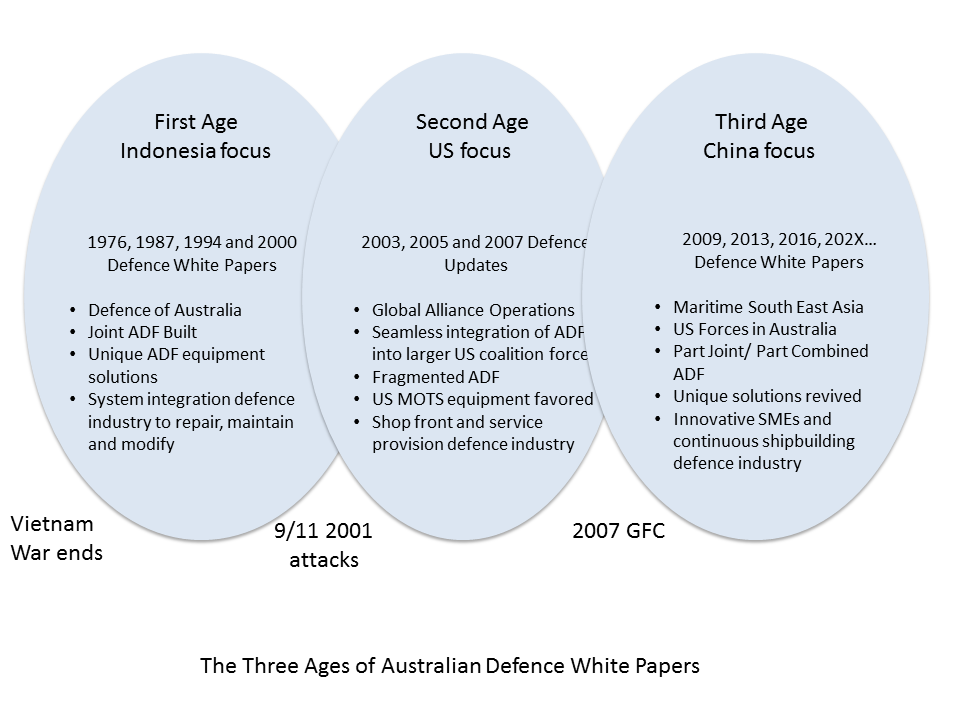

There’s always a certain anticlimax when the latest Defence White Paper is released. The once-feverish anticipation eases as firm plans are set in concrete and potential maybes are accepted or rejected. However, there’s more to White Papers than simply that which creates short-term excitement. This new White Paper is no different. Of particular note is its continuance of what might be termed the ‘third age’ of Australian Defence White Papers. What might this mean downstream?

The first age commenced post-Vietnam with the 1976 Defence White Paper (PDF). This envisaged a force-in-being possessing sufficient capabilities and capacities to manage likely short notice contingencies while providing an expandable core force. Hidden from public view was the belief that Indonesia possessed ‘attributes of both an ally and an adversary‘ (PDF), and although major war was unlikely, low-level harassment was conceivable. Worse still, US support was considered doubtful, making a level of self-reliance crucial. The first age continued with the 1987 Defence White Paper, which declared defence of Australia the main force structure determinant and emphasised air and naval forces. That strategy meant that ADF joint warfare was in vogue, unique Australian military equipment was essential and Australian defence industry had a well-specified function.

The second age was ushered in by al Qaeda’s attacks in 2001. The Australian government was disappointed with the limited American involvement in the 1999 East Timor operation. Now 9/11 offered a way past this; Afghanistan and Iraq were not important in themselves, but rather as opportunities to deepen the Australia-US relationship. This age was formally reflected not in White Papers but in three Defence Updates (2003, 2005 and 2007). This strategy meant ADF joint warfare was out while tactical level forces able to integrate quickly into large US-led coalitions were in. At the same time, there were no longer any unique Australian requirements and Australian industry’s usefulness was mainly as shopfronts for large US companies.

The third age was ushered in by the GFC, albeit unnoticed at the time. This accelerated the relative rise of China as the developed economies stalled and—rightly or wrongly—helped convince the Chinese government that Western nations were in decline and that, consequently, China could become more assertive in its international behaviours and actions. The 2009 Defence White Paper still placed great store in the US alliance but shifted towards viewing the American relationship more in terms of how it could help cope with China’s rise rather than as an end in itself. A timely move because, by coincidence or not, China started to be more assertive in the South China Sea that same year. The signature decisions of this age so far appear to be to dramatically rebalance the Navy’s combat fleet by buying 12 submarines and the semi-permanent, long-term basing of USMC combat forces in Darwin.

The three ages construct describes how Australia’s defence focus has moved across the last forty years—from fretting about Indonesia, to bandwagoning with the US to, today, managing China’s rise. A pleasingly minimal framework, but so what? Considering the new White Paper and these earlier ages might give us some clues to the future.

First, the new White Paper foresees independent operations in maritime Southeast Asia. This suggests a return to the first age’s focus on joint warfare over simply augmenting American forces. Unique Australian requirements may emerge yet again, as the needs of the small ADF aren’t necessarily the same as those of the vast US military. The 12 submarines may be an indicator of that. Six would be adequate for intelligence support operations if bandwagoning with the Americans was the primary goal. By contrast, 12 unique boats use up a lot of scarce budget for a very Australian specific purpose. Moreover, the 1100 Hawkeis, and the rise of continuous ship-building, are consistent with a return to Australian industry having some strategic importance—though other explanations could be offered. But there’s a first age warning of stormy waters. Army has long railed against its lesser place in the first age’s maritime focus. And with the new White Paper’s focus on China in maritime Southeast Asia, land forces may once again not be the highest strategic priority, which is an issue that’s perhaps already grasped. Will Army’s new role operating land-based anti-ship missiles be enough to deflect future critics?

Second, the new White Paper stresses regional engagement. It places heightened importance on generating Australia’s regional influence, being a respected security actor and creating effective security partnerships. All good stuff, but unlike in the first and second ages, America is vitally interested in our region. Anthony Bergin insightfully writes ‘the US could squeeze us out of regional defence engagement by being a bigger and better partner. We have to work harder to retain our influence.’ This suggests that, unlike the second age’s subordinate position to the US, the new strategic focus on China calls for a carefully nuanced autonomy. Australia now seeks security with Asia (not from Asia as in the first age) and that requires taking careful advantage of the US alliance rather than being subsumed by it. That’s a big ask.

Third, the earlier points raise the issue that strategy-making will be both important and difficult. Important, as this third age raises new challenges, including with alliance management that haven’t been faced for a long time. The strategy from the first age proved effective, albeit never really needing to prove itself. Events showed such a force structure could be used for other tasks, but didn’t stress test it in its core role. The second age passed strategy-making to the Americans. Now the onus, by our choice, shifts onto us. Will this challenge mean that, over time, we swing back to bandwagoning and the second age’s strategy outsourcing?