The US and China came to Singapore’s Shangri-La security dialogue to argue and score points, to talk and to taunt.

The face-off presented as drama and fight.

As the reigning champ, the US got to throw the first public punch in the first session on day one. As challenger, China starred in a mirror session, to start day two. This was conference scheduling to express the drama that today obsesses the Indo-Pacific.

Beyond the public performances, US Defense Secretary Lloyd Austin and China’s Defence Minister Wei Fenghe had a bilateral meeting plus two ministerial forums chaired by Singapore’s Defence Minister Ng Eng Hen.

Austin kicked off on Saturday because at every Shangri-La Dialogue since the second was held in 2003, the US defence secretary has been the first speaker at the first session. Being number one has its privileges.

Austin was 25 minutes into his speech before he named China, but it was central to his description of the Indo-Pacific as the ‘core organising principle’ of US national-security policy:

Today, the Indo-Pacific is our priority theatre of operations. Today, the Indo-Pacific is at the heart of American grand strategy … And today, American statecraft is rooted in this reality: no region will do more to set the trajectory of the 21st century than this one. And so the Indo-Pacific is our centre of strategic gravity.

Austin offered plenty of new stuff to illustrate that strategy: AUKUS, three Quad summits, ‘close partnership with Pacific island countries’ and ‘new opportunities for cooperation among Japan, the Republic of Korea and more’. It’s been a while since a US defence secretary listed the South Pacific among his top issues or expressed optimism about Japan and South Korea working together.

Austin promised that the US would stand by its friends as they upheld their rights in dealing with ‘a more coercive and aggressive’ China that was using ‘political intimidation, economic coercion or harassment’:

We do not seek confrontation or conflict. And we do not seek a new Cold War, an Asian NATO, or a region split into hostile blocs … [G]reat powers should be models of transparency and communication. So we’re working closely with both our competitors and our friends to strengthen the guardrails against conflict. That includes fully open lines of communication with China’s defence leaders to ensure that we can avoid any miscalculations. These are deeply, deeply important conversations.

For a long time, China treated Shangri-La with suspicion, fearing some form of Anglo entrapment at an event run by Britain’s International Institute for Strategic Studies in partnership with the Singaporean government.

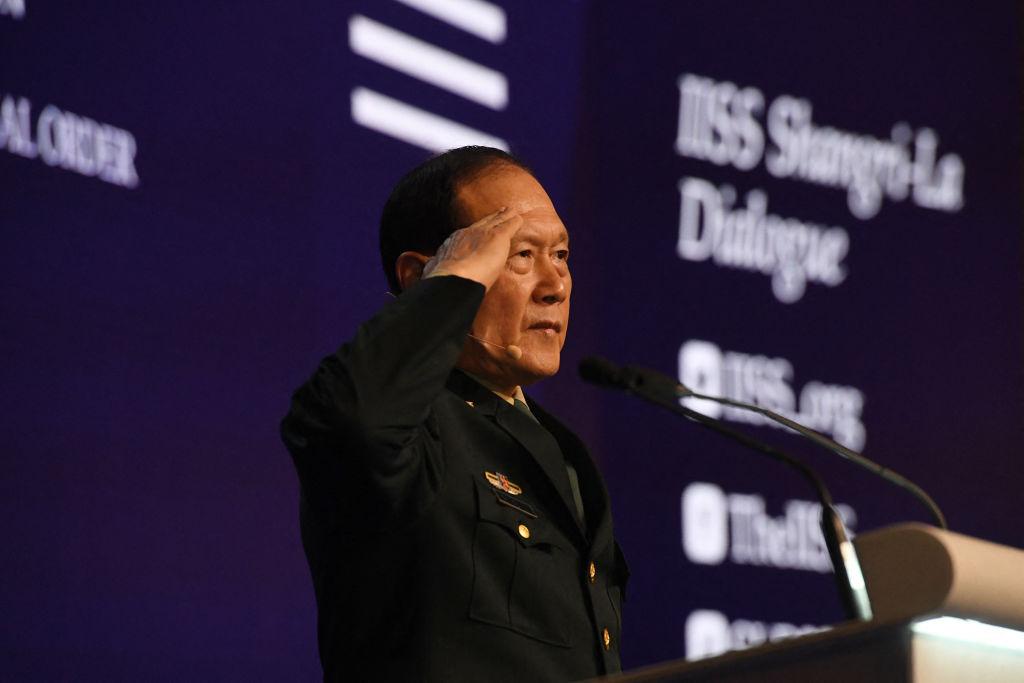

The IISS kept promising Beijing that if it sent its defence minister, they’d get equal billing. This year is the third time China’s defence minister has attended. The first such visit was in 2011 and General Wei attended the previous, pre-pandemic Shangri-La Dialogue in 2019. His performance in 2019 (promising an equal readiness to talk or fight) set an instant Shangri-La tradition of mirror sessions for China and the US.

As with other regional forums, China has worked through its initial caution and started to use the pulpit, showing up ready to rumble. That’s despite the uncomfortable fact that almost half the defence minister’s performance time was free-form rather than scripted when he faced a volley of questions following the speech. Wei stepped up to the challenge with a crisp military salute at the start of his speech, another salute at the end of the speech, and a third after questions.

China’s defence minister said he rejected the ‘smearing accusations and threats’ of the US defence secretary and Washington’s ‘obsession with values-based alliances’. The US Indo-Pacific strategy, Wei said, was an attempt to build a small, exclusive group that can hijack countries in the region.

In facing questions, Wei used boilerplate to deflect pointed jabs from the audience. Would China use force to overturn the status quo with Taiwan? ‘Taiwan is Chinese Taiwan. It’s a province of China,’ he replied.

A delegate from Vietnam pinged the general’s claim that China had never seized an inch of another nation’s country, pointing out that China had often invaded Vietnam (‘I assume your framework is for the future?’). Read the history carefully, responded Wei.

He faced questions on why China had not denounced Russia for violating Ukraine’s sovereignty. Why had China not condemned Russia’s ‘unprovoked, illegal aggression’? The general’s reply was to call for peace talks. The only condemnation was of those giving weapons to Ukraine and imposing sanctions on Russia, because such actions would not solve the problem.

The Australian Financial Review’s Emma Connors raised the incident over the South China Sea on 26 May when a Chinese fighter jet flew dangerously close to a Royal Australian Air Force P-8 surveillance aircraft, releasing aluminium chaff that was ingested into the P-8’s engine. Connors noted a Chinese statement calling Australia’s patrol provocative and threatening serious consequences. What consequences?

Wei’s boilerplate didn’t mention Australia or the actions of China’s jet: ‘China grows its defence capabilities to ensure national security and ensure peace. The development of the military of China is never intended to threaten others or seek hegemony. China is never a threat and has never threatened any others. China will not be the bully.’

Shangri-La did its usual important job, bringing together a dizzying array of defence ministers and military officers from across the Indo-Pacific and Europe, cramming Saturday and Sunday with speeches, bilaterals and multilaterals. As Singapore’s Defence Minister Ng observed, this is ‘the Mount Everest of speed dating’.

Lots of exchanges. Much talking. Perhaps some understanding.

Whether the dialogue shifted any Chinese or US views is moot. Much of the show was aimed at persuading others. And the taunts weighed as much as the talk.