When it comes to transnational serious and organised crime in the Asia–Pacific, it’s hard not to be pessimistic. At the moment, Southeast Asia is on the brink of a methamphetamine (ice) epidemic, with cheap and high-purity drugs being produced at an industrial level. Harm-minimisation safety nets are few and far between in the region, so the impact of any epidemic is likely to be dire.

Australia’s international policing efforts are concerned with far more than altruism. Over recent years, Australia’s domestic organised crime problem has become increasingly transnational. And the costs of that crime have never been higher. Earlier this year, the Australian Institute of Criminology estimated that organised crime costs the country between $23.8 billion and $46 billion a year.

The continued globalisation of Australia’s serious and organised crime problem is resulting in a shift in policing responsibilities from the states and territories to the Commonwealth. In the wake of these changes, Commonwealth law enforcement agencies, like the Australian Federal Police, are facing a widening gap between the amount of crime that’s occurring and their capacity to respond to it. This makes the disruption of criminal groups offshore more important than ever.

These developments mean that Australia’s international law enforcement efforts, be they police-to-police cooperation or capacity development, are critical. The theory underpinning this policy perspective is that raising police capability across the Asia–Pacific and improving international cooperation will contribute to the disruption of transnational organised crime groups.

Unfortunately, Australia’s international policing efforts are under significant financial pressure. Fiscal responsibility is necessary for any government, especially one that is attempting to return a budget to surplus, but there are also tough policy decisions on issues like Australia’s commitment to the international criminal police organisation, Interpol, that need to be made.

While there are other international policing organisations, including Europol and Aseanapol, Interpol is the world’s largest and arguably its only truly global policing organisation. Although Interpol can trace its origins to 1914, for all intents and purposes its worldwide, or perhaps universal, status emerged in 1956. That year Interpol adopted a modernised constitution and became truly autonomous by starting to collect dues from member countries.

Interpol supports cooperation between criminal law enforcement agencies from different countries. It performs an administrative liaison function on behalf of the law enforcement agencies of its member countries, providing communications and database assistance.

While Interpol’s formal role is to ‘enable police around the world to work together to make the world a safer place’, it is its promotion of information and intelligence that is critical to combatting transnational serious and organised crime. Interpol’s collaborative form of cooperation seeks to address disincentives and barriers to criminal intelligence-sharing, such as language, culture and bureaucratic differences.

Australia has always been a global leader in police-to-police cooperation and an active regional partner in police capacity development in the Asia–Pacific. So it’s only natural that Australia has also long been a big supporter of Interpol. In the ASEAN region, law enforcement agencies have invested heavily in Interpol, as it provides secure communications that would otherwise not be available.

The Australian Federal Police has had two senior staff with Interpol for several years: one with its Global Complex for Innovation in Singapore and the other as the executive director of police services in Lyon.

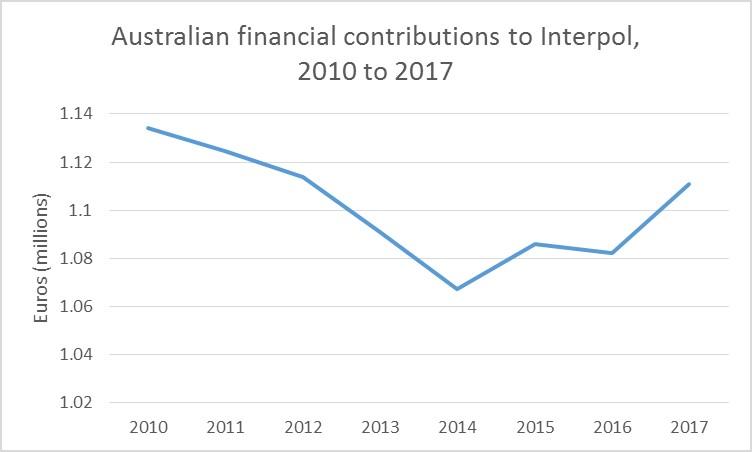

Australia’s financial commitment to Interpol is made directly from the AFP budget. Consecutive efficiency dividends, and lapsing policy initiatives, have had a big effect on the AFP’s budget, which in turn has directly affected the organisation’s international policing efforts. As shown in the graph below, Australia’s contributions to Interpol were in steady decline until 2014 and are yet to return to 2010 levels.

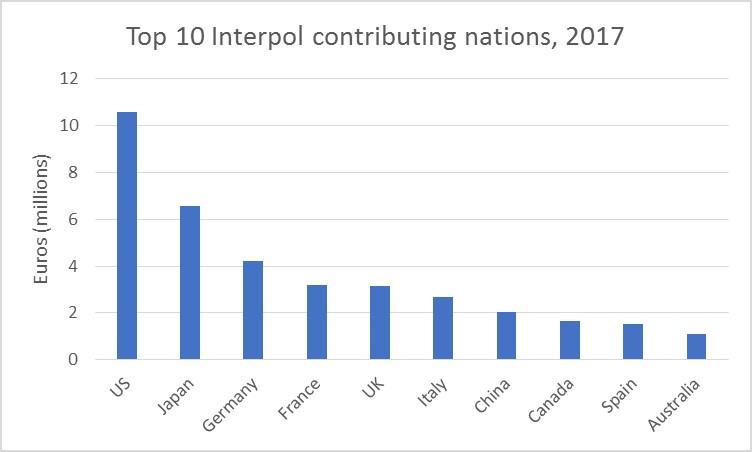

Should we really be concerned about the overall drop in funding given that, as illustrated in the next graph, Australia remains in the top 10 contributors to Interpol?

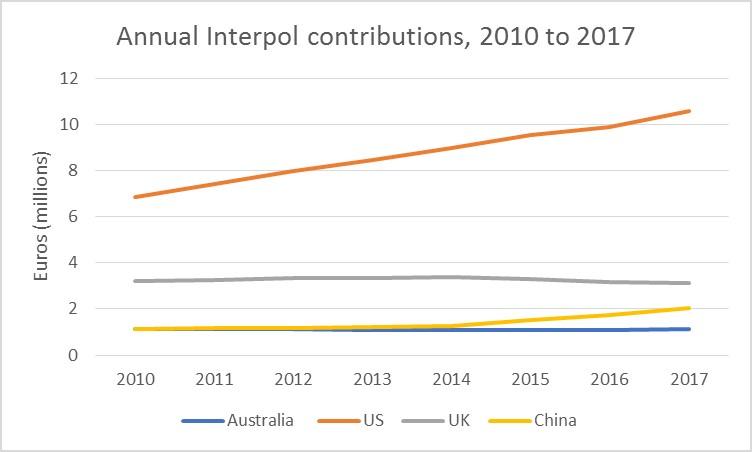

A longitudinal analysis of these contributions shows that Australia’s Interpol funding in terms of purchasing power is in steady decline in comparison with countries like China and the US.

The decision for government shouldn’t necessarily be a binary one about whether or not to invest further in Interpol. Australia’s contribution to international policing shouldn’t be measured only in terms of Interpol; our other efforts across the globe, especially in capacity development in the Asia–Pacific, are extensive.

It’s fair to say that continued erosion of Australia’s contributions to Interpol will see a decline in our influence within the organisation. However, further investment in Interpol shouldn’t necessarily come at the cost of capacity-development efforts closer to home, which are critical in tackling Australia’s transnational serious and organised crime challenges.

While this is largely a law enforcement issue, it should also be viewed through a geopolitical lens. Australia has likely benefited more from bilateral police-to-police arrangements than from multilateral mechanisms, but that doesn’t mean we should neglect international engagement through these forums.

The bottom line here is that the Interpol funding dilemma illustrates that it’s as good a time as any to reconsider some Commonwealth law enforcement policies. It also illustrates that while the statutory independence of law enforcement agencies needs to be maintained, policy decisions on issues like this need to be considered in light of Australia’s broader national security strategy.