We’ve known for a while that SEA 1000, the Defence Department’s future submarine program, is going to cost a lot of money—we just haven’t known exactly how much. But as time moves on and Defence releases more data, we’re starting to get a better sense of the program’s cost.

Let’s review what we know about the cost of the program. In 2012, ASPI estimated it to be around $36 billion, in constant dollars, which doesn’t take inflation into account. But the Australian government, including the Defence Department, works in ‘out-turned’ dollars, which includes an allowance for inflation. Once out-turned, that number becomes $50–60 billion.

While many commentators suggested that that was way too high, the 2016 integrated investment program provided a number of ‘>$50 billion’. But later, at Senate estimates, Defence officials conceded that that was a constant-dollar figure, so ASPI converted it to an out-turned number of $79 billion based on a projected annual inflation rate of 2.5%, a pretty modest amount for military equipment.

Those dollars aren’t ‘approved’ in Defence’s parlance, which means the department doesn’t have the government’s approval to spend all that money. The recent release of Defence’s 2018–19 annual report confirmed that the total approved budget is now $5,963 million after the government approved the latest tranche of funding of $3,723 million (web table D.3). That apparently gets the program to the end of the design phase and to the start of construction in 2022–23; $6 billion doesn’t buy us any actual submarines.

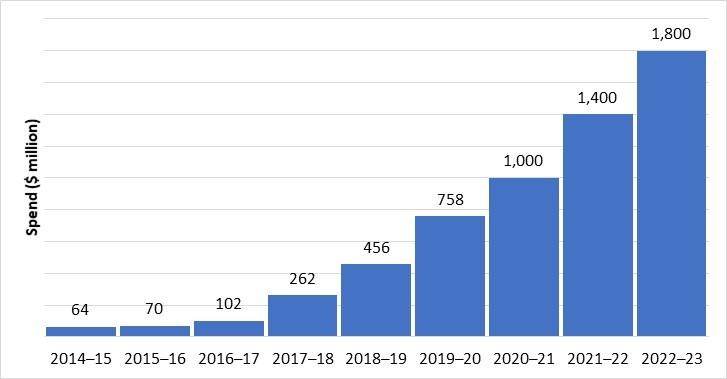

It’s also important for any business to understand its cash flow—that is, how much it needs to spend each year. We can determine historical cash flows from Defence’s reporting. The program’s annual spend is increasing rapidly and, according to advice from Defence, it will be around $750 million in 2019–20. We can also estimate the cash flow for the next few years. The total approved budget for the program to 2022–23 is $5,963 million. From figure 1, we can see that the cumulative spend to the end of this financial year will be around $1,712 million, leaving $4,251 million for the next three years. That will likely be apportioned something like how we’ve done it in figure 1.

Figure 1: Future submarine program annual spend, 2014–15 to 2022–23

That’s a lot of money to spend every year. If correct, those numbers, when combined with the costs of the future frigate program, will soon start to cause significant problems for the rest of Defence’s investment portfolio. So, are they reasonable? We can check by taking a look at the corresponding data for the Collins-class submarine and the nearly completed air warfare destroyer (AWD) programs.

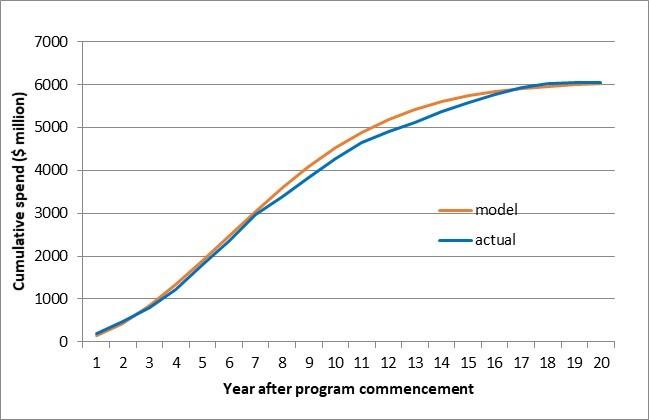

As described in a previous Strategist piece, a useful tool for modelling the cost of major projects is the Rayleigh–Norden curve. It’s a simple two-parameter model in which the overall cost and duration of the program are the only variables. Despite its uncomplicated form, this model fits the two historical programs very well. Figure 2 shows the modelled and actual cumulative spending on the Collins-class program from 1987 to 2007.

Figure 2: Collins-class submarine program spending, model versus actual

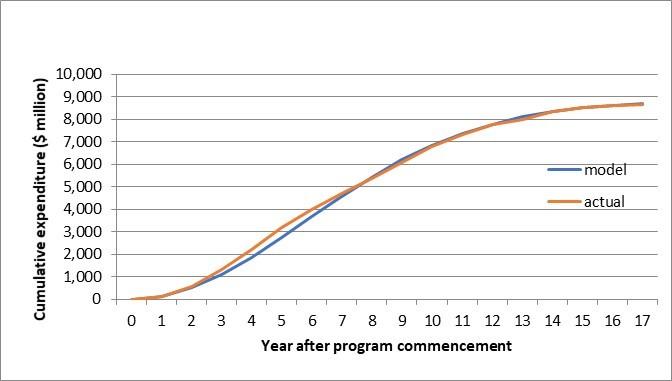

As figure 3 shows, the agreement between the modelled and actual spends on the AWD program is even better. (The correlation between the two curves is 99.9%.)

Figure 3: Air warfare destroyer program spending, model versus actual

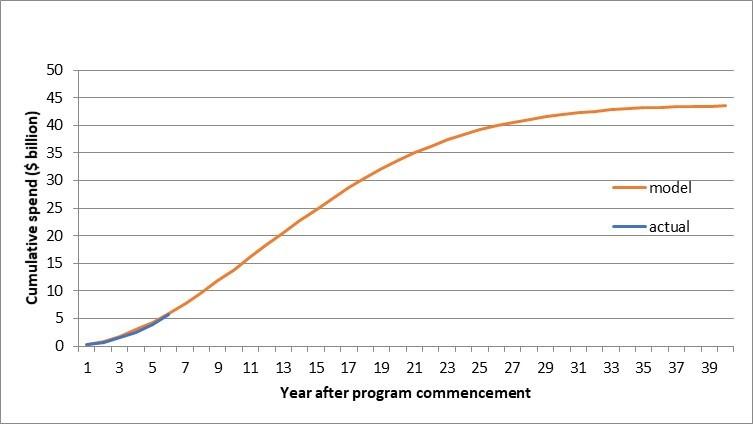

So, having convinced ourselves that the model is a pretty good predictor of the spending spread of Australian naval shipbuilding programs, it seems reasonable to apply it to the future submarine program and see what happens. Assuming that it’s a 40-year program that will run from approval in 2016 out to the mid-2050s (consistent with public statements on delivery rates) at a total cost of $43.7 billion in today’s dollars (the inflation-adjusted value of ASPI’s earlier $36 billion estimate), the calculated curve is shown in figure 4.

Figure 4: Future submarine program spending, model versus actual

Based on those calculations we can make two observations. First, despite the fact that Defence will have spent around $6 billion before the boats start being built, it’s certainly not an overspend compared with previous programs. In fact, when compared with ASPI’s estimate, spending seems to be right on track. (Alternatively, if the ‘>$50 billion’ figure is right, it would be behind the predicted spend.)

Second, and far more importantly, the biggest outlays are yet to come. If the program tracks according to the Rayleigh–Norden model—and there’s no reason to think it won’t—the second and third five-year blocks will require investment of $9.6 billion and $10.9 billion, respectively. That’s close enough to $2 billion per year (or more, in the worst case) being absorbed by this one program.

We could expect the frigates and offshore patrol vessels combined to be spending a similar amount. In other words, close to 10% of the entire defence budget, and more like 30% of the capital investment budget (see chapter 6), will be going into naval shipbuilding for a full decade.

That’s a big opportunity cost to other force modernisation initiatives. And it’s not likely to improve much once the peak spend of the current shipbuilding projects is passed. A commitment to continuous in-country naval shipbuilding means that the planning and designing of the next generation of vessels will happen concurrently with the later phases of delivery of today’s megaprojects.

We can only hope that the revolutionary technologies of tomorrow will be affordable with what’s left in the kitty.