The crises, conflicts and wars that are currently raging highlight just how profoundly the geopolitical landscape has changed in recent years, as great-power rivalries have again become central to international relations. With the wars in Gaza and Ukraine exacerbating global divisions, an even more profound geopolitical reconfiguration—including a shift to a new world order—may well be in the works.

These two wars heighten the risk of a third, over Taiwan. No one—least of all Chinese President Xi Jinping—can watch the United States transfer huge amounts of artillery munitions, smart bombs, missiles and other weaponry to Ukraine and Israel without recognising that American stockpiles are being depleted. For Xi, who has called Taiwan’s incorporation into the People’s Republic a ‘historic mission’, the longer these wars continue, the better.

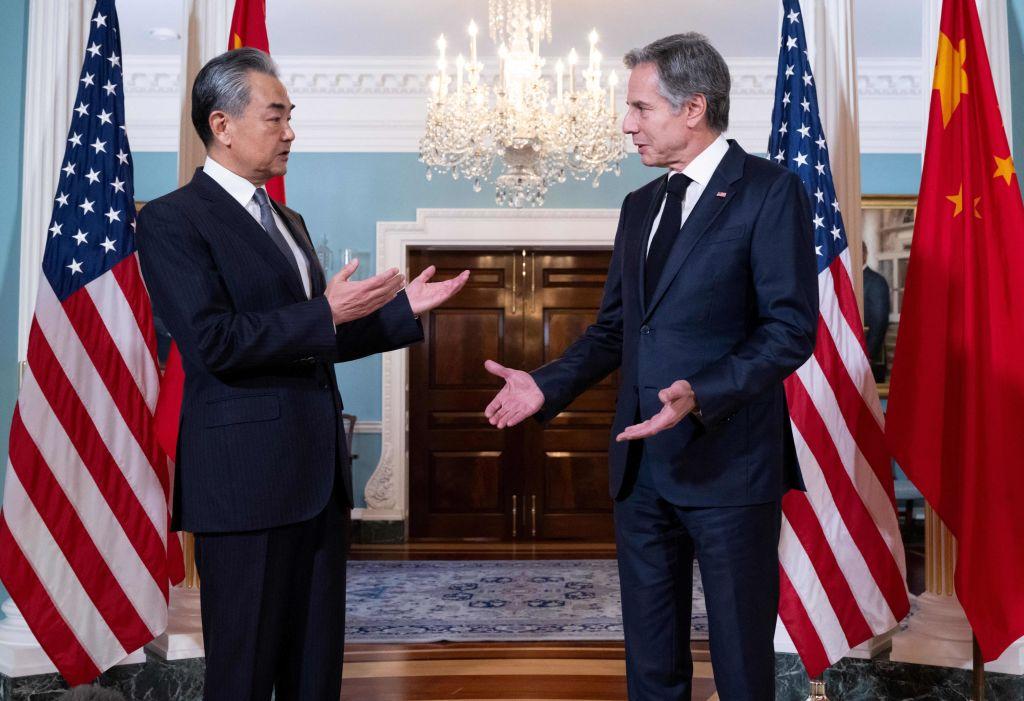

US President Joe Biden understands the stakes and is now seeking to defuse tensions with China. Notably, after sending a string of cabinet officials to Beijing, Biden’s planned summit talks with Xi on the sidelines at the APEC forum this week in San Francisco are set to steal the spotlight. And he and his G7 partners have stressed that they are seeking to ‘de-risk’ their relationship with China, not ‘decouple’ from the world’s second-largest economy.

Whatever one calls it, this process is set to reshape the global financial order, as well as investment and trade patterns. Already, trade and investment flows are changing in ways that suggest that the global economy may be split into two blocs; for example, China now trades more with the global south than with the West. Despite the high costs of economic fragmentation, China, seeking to reduce its vulnerability to future pressure, has been quietly decoupling large sections of its economy from the West.

In no small part, the US has itself to blame for this situation. By actively facilitating China’s economic rise for four decades, it helped to create the greatest rival it has ever faced. Today, China boasts the world’s largest navy and coast guard, and is overtly challenging Western dominance over the global financial system and in international institutions. In fact, China is working hard to build an alternative world order, with itself at the centre.

Though the current system is often referred to in neutral-sounding terms such as the ‘rules-based global order’, it is undoubtedly centred on the US. Not only did the US largely make the rules on which that order is based, but it also seems to believe itself exempt from key rules and norms, such as those prohibiting interference in other countries’ internal affairs. International law is powerful against the powerless, but powerless against the powerful.

When it comes to creating an alternative world order, the current conflict-ridden global environment may well work in China’s favour. After all, it was war that gave rise to the US-led global order, including the institutions that underpin it, such as the International Monetary Fund, the World Bank and the United Nations. Even reforming these institutions meaningfully has proved very difficult during peacetime.

This is certainly true for the UN, which appears to be in irreversible decline and increasingly marginalised in international affairs. The hardening gridlock at the UN Security Council has caused more responsibility to be shifted to the UN General Assembly, which was forced, notably, to adopt a resolution on the war in Gaza calling for a ‘humanitarian truce’ and an end to Israel’s siege. But the General Assembly is fundamentally weak, and, in contrast to the Security Council, its resolutions are not legally binding.

As US-led institutions deteriorate, so too does America’s authority beyond its borders. Even Israel and Ukraine—which depend on the US as their largest military, political and economic backer—have at times spurned US advice. Israel rebuffed America’s counsel to scale back its military attacks and do more to minimise civilian casualties in an already dire humanitarian situation in Gaza. US officials have blamed Ukraine’s wide dispersal of forces for its stalled counteroffensive.

Beyond the global reordering that the Sino-American rivalry appears to be causing, important regional shifts are possible. A protracted conflict in Gaza could set in motion a geopolitical reorganisation in the Greater Middle East, where nearly every major power—except Egypt, Iran and Turkey—is a 20th-century construct created by the West (especially the British and the French). Already, Israel’s war is strengthening the geopolitical role of gas-rich Qatar, a regional gadfly that has become an international rogue elephant by funding violent jihadists, including Hamas.

If the conflict spreads beyond Gaza, the geopolitical implications would be even further-reaching. Whatever comes next, Ukraine may well be among the biggest losers. As Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky has acknowledged, the war in Gaza already ‘takes away the focus’ from his country’s fight against Russia at a time when Ukraine can ill afford a slowdown in Western aid.

Yet, more forces and trends—including Russia’s increasingly militarised economy, China’s stalling growth and the growing economic weight of the global south—are making fundamental changes to the international order more likely. Meanwhile, the world is grappling with widening inequality, rising authoritarianism, the rapid development of transformative technologies like artificial intelligence, environmental degradation and climate change.

Though the details are impossible to know, a fundamental global geopolitical rebalancing now appears all but inevitable. The spectre of a sustained clash between the West and its rivals—especially China, Russia and the Islamic world—looms large.