The Central Committee of the Chinese Communist Party has accepted the resignation of one of its own most highly ranked members, former foreign minister Qin Gang, highlighting Xi Jinping’s continuing lack of trust in some of his own hand-picked officials.

Qin’s exit, along with that of other senior officials dismissed from office in the past year, was confirmed on 18 July at a key Central Committee meeting held every five years, known as the third plenum.

Xi’s loss of trust in these senior officials, and allegations of corruption that underlie some of them, sit uncomfortably close to the centre of power in China. It is a situation that likely makes him doubt information and advice he receives on the issues he cares about most. Some, such as military preparedness, leave little room for miscalculation.

Qin mysteriously disappeared from public view in June 2023, was removed from his post at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs in the following month and was stripped of his title as state councillor in October. His fall from grace prompted intense speculation about how someone who was once known as a close aid of Xi and who had risen so quickly in the foreign affairs system could seemingly disappear just as quickly and without explanation. No known charges have been lodged against him, he has not been expelled from the party, and, with his final resignation, in the end he has been let off gently. That leaves room for different interpretations of what has happened.

With a long career in the foreign ministry, Qin was appointed China’s ambassador to the United States in December 2022. Just 17 months later, he became foreign minister. The speed of his promotion appeared to be intended to help ease tensions between the US and China. His disappearance came after he had been in the job for seven months and had reportedly had an extra-marital affair while in the US that resulted in a secret child born with American citizenship.

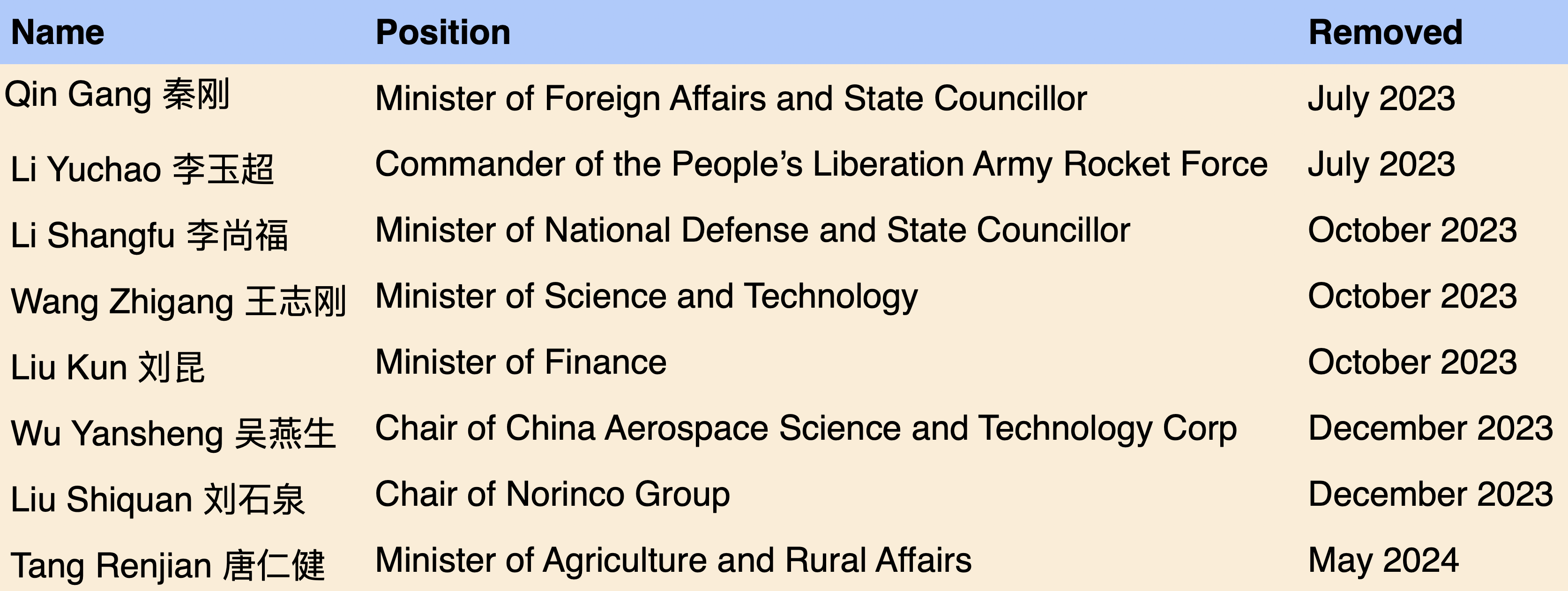

But Qin is only one of a growing list of senior officials removed from office in the past year, some explicitly for corruption, others without public explanation. There was speculation that the third plenum had been delayed due to the corruption investigations of Central Committee members. The most prominent of those being investigated include defence minister Li Shangfu, whose expulsion from the party and its Central Committee was announced in June (and confirmed by the plenum this week). Others are former science and technology minister Wang Zhigang and former finance minister Liu Kun, whose removal from his ministerial position was announced at the same time as Qin’s dismissal as a state councillor. This table lists the most significant dismissals of the past year:

Several of these people had policy roles that were important to achieving by mid-century Xi’s vision of the ‘national rejuvenation of the Chinese nation’, meaning to make China the world’s leading economic power and the most influential political actor in global politics.

In addition to the removal of the defence minister and the commander of the People’s Liberation Army Rocket Force, nine other military officials were also purged last year—in part due to corruption that led to missiles being filled with water instead of fuel, according to US intelligence assessments. Such incidents have likely eroded Xi’s confidence in the armed forces’ capabilities and set back his military modernisation mission.

If Xi wants the party to achieve his vision for China, he needs to know he can trust his officials to give him accurate assessments and faithfully carry out his orders. The question of whom he can trust is clearly on his mind: in recent months, he has said he wants officials to ensure his orders are carried out ‘smoothly’ and that the PLA must always remain steadfastly ‘loyal and reliable’ to the party and therefore to Xi personally.

Since his appointment as party leader in 2012, Xi has made fighting corruption within it a central feature of his rule, removing both high and low ranked officials in ministries, military branches, and state-owned enterprises. Millions have been prosecuted.

Xi began his third term as leader at the 20th party congress in October 2022 by filling the upper echelon of the party with personal allies and loyalists, some of whom had been with him for decades. These were all men (there were no women) whom he thought he could trust to do as he said and even tell him what he needed to hear. Within less than a year, he was having to cut some of his own proteges loose.

It’s not easy being number one, particularly one who has become so central to all aspects of governing China and who is now even more reluctant to delegate than before. Each one of Xi’s decisions affects every facet of China’s society, prospects and international standing. Xi will likely always need to have one eye looking over his shoulder for the next Qin Gang to appear. And in the end, he is completely alone with it all.