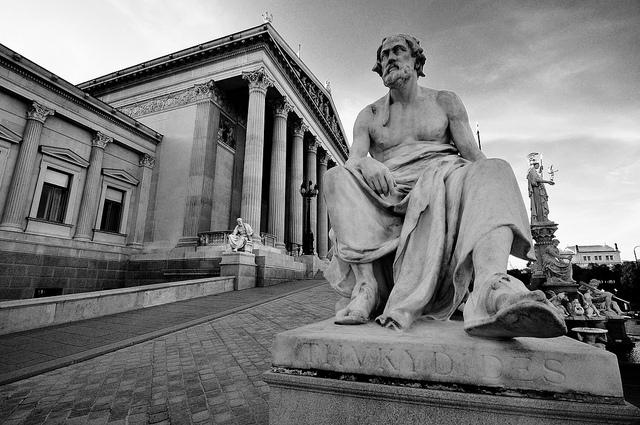

Realists argue there’s only one genuine philosophical principle to guide a nation’s foreign policy. In the first recorded debate between realists and idealists, Thucydides reported the Athenians telling the Melians, ‘the strong do what they can and the weak suffer what they must’. Thucydides foreshadowed the realist worldview that nations, ‘are concerned with their own security, act in pursuit of their own national interests, and struggle for power’. Realists believe that the international environment is anarchic and that, consistent with their capacity and opportunities, states will always act in their own economic, ideological and security interests. Philosophically, the new Foreign and Trade White Paper (FTWP) should be firmly based in realism.

An overriding, one size fits all, ‘philosophical framework to guide Australia’s engagement, regardless of international events‘ will either prove to be unworkable—and be ditched at the first intractable crisis or problem—or, if followed irrespective of the specifics of a situation, lead to increased tensions and conflict as other nations pursue their own interests with vigour. Effective implementation of foreign policy involves compromise and accommodation, as well as pursuit of objectives. Sometimes avoiding harm to one’s national interest and mitigating or minimising harm is a good outcome.

The realist paradigm that drove Cold War strategies appeared to be outdated after the fall of the Soviet Union. In the aftermath, George H.W. Bush spoke of a new global order: ‘A world where the rule of law supplants the rule of the jungle’; adding that ‘No peaceful international order is possible if larger States can devour their smaller neighbours’. But political realists are feeling smug these days. The underlying anarchy of the international environment appears to be pushing through the thin veneer of the post-Cold War order. Nations are increasingly ignoring the web of conventions, norms and rules governing the behaviour between states that seemed largely settled.

The rules-based order—or liberal internationalism—pursued by the US and its allies appears to be fraying. The international law governing interstate conflict has been flouted with impunity on numerous occasions so far this century. The US-led invasion of Iraq is considered by many to be a breach of international law. The case is strong that ‘no international or domestic legal act can justify’ the Russian invasion of Georgia in 2008 or the creation of the separatist states. Similarly Russia’s annexation of Crimea is demonstrably ‘a fundamental breach of international law‘. Russia’s actions in Aleppo are seen as beyond the rules of war governing attacking civilians. The Saudi air campaign in Yemen has shocked its allies. That the Arbitral Tribunal found China’s South China Sea claims to be extinguished has had no tangible effect, as China refuses to acknowledge its jurisdiction and continues its activities. But those a just the tip of the iceberg.

The neoliberal consensus underlying globalisation and the advance of free trade and liberalisation of capital is breaking down. Financial liberalisation and globalist economics are being questioned in the wake of the 2008 Global Financial Crisis. The Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (TTIP) and the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP), both of which were touted as vehicles for economic growth and greater security are—if not fatally wounded—unlikely to come to fruition in their current forms. More significantly for our foreign policy formulation, the vigorous pursuit of those trade arrangements has produced a nativist reaction in the US and has been a rallying cry for nationalist opponents of the EU project. The Brexit vote was as much a rejection of the rules-based European Union as it was a rejection of Brussel’s continued advocacy of free trade agreements. The British reaction put nationalistic considerations first.

To drive Australia’s foreign policy on the assumption that we possess the only legitimate organising principles for the world and that our policy should be to ‘shape the thinking of other nations’ not only sounds like cultural and political imperialism, but is more crusade than policy. Russia and China are revisionist powers—a fact neither hides—with realist approaches to foreign affairs. China’s success in Africa is directly related to realist policies. The spread of liberal democracy has been halted or reversed in countries like Thailand and Turkey, and around the world putative democracy is a screen for sham elections and authoritarianism. The ardent pursuit of liberal internationalist norms is likely to be unproductive policy.

If the FTWP is to be of long-lasting benefit in the conduct of Australian foreign policy—rather than a liberal internationalist wish list—it must be firmly based in a realist understanding.