Back in 1970, Time magazine ran an article entitled ‘Toward the Japanese Century’. More recently, in 2005 Mark Leonard was writing about the ‘European Century’. Today you’d be hard pressed to find anyone who’d envisage a ‘Japanese Century’ or, Nobel Peace Prize notwithstanding, a European one.

But both these ideas got me thinking about the term ‘Asian Century’ which is currently all the rage in Canberra. What do we mean by it and will we still be talking about it in forty years from now or even five years from now?

The term is of course best known in connection to the government’s upcoming Asian Century White Paper which has been preceded by ‘Asian Century’ essay competitions, community events and blogs. The term now litters newspaper columns and even university courses. It has become an overnight cliché, but has received little scrutiny.

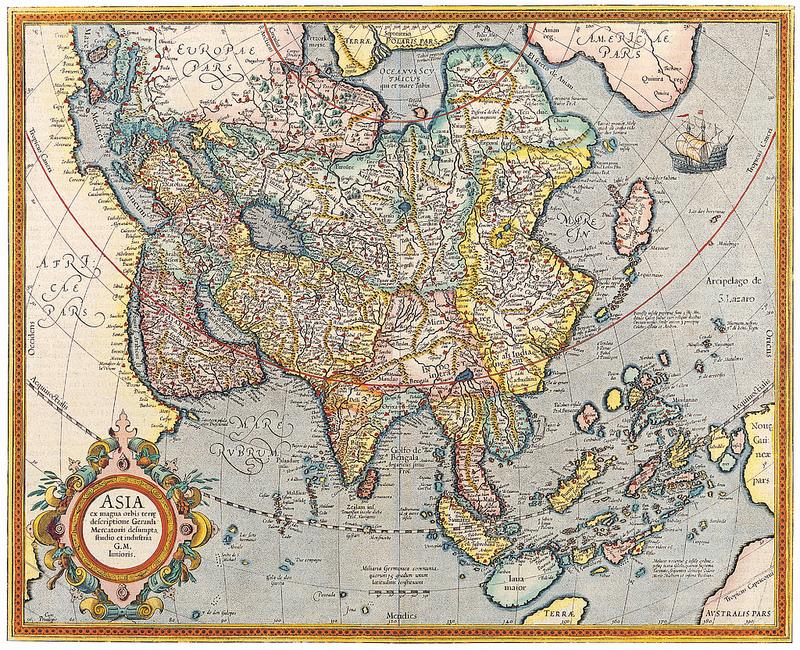

When exactly did the ‘Asian Century’ begin and when will it end? Indeed, what do we mean by Asia? These points may appear glib, but they important; after all our language frames our enquiry.

The idea of a country or a region owning a century goes back to a Life magazine article written by Henry Luce in 1941, in which he called for the creation of ‘the first great American century’ Luce’s rhetoric suggests that he saw the United States as the successor of European civilisation. Today Presidential candidates speak of a ‘new American century’. Certainly no one in the US speaks of an Asian Century because the term implies at best a marginalisation of American power.

Herein lays the problem. The term is agenda driven; it is not neutral. Those who refer to the ‘Asian Century’, such as Professor Hugh White, tend to use it to argue that the era of uncontested US primacy is at an end. Conversely those who advocate renewed American engagement in the region, including the Americans themselves, tend to cling to idea of the ‘Asia-Pacific’.

The term ‘Asian Century’ is a good use of language in some ways and bad in others. It is good because it has broadened the debate. It is a convenient short hand to get the broader public thinking about the region, its potential future and Australia’s place in it. We should thank Hugh White for this; he more than anyone else in many years has restored strategy to a central role in the public conversation.

However, the term has its drawbacks because it seeks to frame that debate within certain parameters. An ‘Asian Century’ presupposes that the US will be either unable or unwilling to continue exercise pre-eminence. It is far from clear that this is the case. Indeed, all indications are that Washington today is more committed to the region than it has been for a generation.

It’s not just the US that is marginalised by the term ‘Asian Century’—Australia is undoubtedly a Pacific nation but our credentials as an Asian one are shaky at best. A recent conference entitled ‘Australia in China’s Century’ only heightened the sense of Australia as a bit player in the affairs of greater states.

At its worst, the term may foster group think and narrow the debate. This is not to say that it doesn’t serve a purpose but at the very least we should consider exactly what that purpose is.

Finally, there is a certain hubris in the idea or writing history before it takes place. Perhaps it is better to leave off this pre-emptive labelling of centuries altogether.

Cam Hawker is a lecturer in Political and International Studies at the UNSW (ADFA) and vice-president of the ACT Branch of the AIIA. Image courtesy of Flickr user falco500.