A scandal is brewing at the World Bank. The Economist recently suggested that the premature departure of its chief economist, Pinelopi Goldberg, is related to the bank’s suppression of a study showing that a material share of its lending to the countries most in need winds up in the hands of corrupt governing elites and shows up as deposits in tax havens.

The Financial Times obtained and published a copy of the bombshell paper, which is dated December 2019; it was later released by the bank. The study examines the financial flows from the 22 countries making greatest use of World Bank lending. They are mainly nations from Africa and Central Asia that receive funding from the World Bank accounting for at least 2% of GDP and total aid receipts averaging 10% of GDP.

Nations in the study include Afghanistan, Armenia, Ethiopia, Mozambique, Rwanda, Uganda and Guyana. The largest tax haven deposits were held by residents of Madagascar, Rwanda, Tanzania, Zambia and Burundi.

The study, by World Bank researcher Bob Rikjers, the University of Copenhagen’s Niels Johannesen and BI Norwegian Business School’s Jørgen Anderson, examined World Bank loans over a 20-year period to 2010.

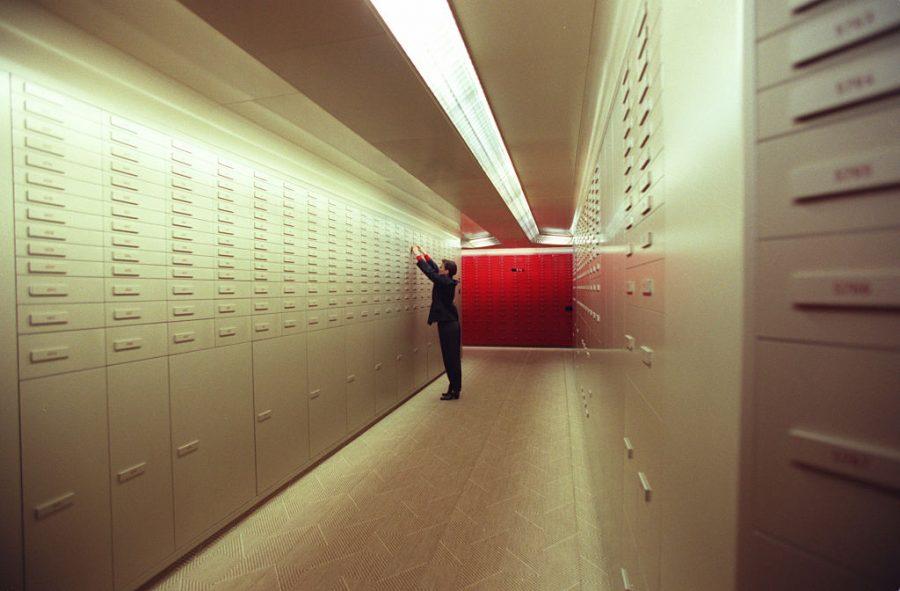

It then turned to the Bank for International Settlements, which is a Geneva-based institution often described as the central bankers’ central bank, for data on bank deposits in tax havens. The BIS collects data on bank deposits from the residents of 200 countries in 43 international financial centres and makes available confidential data on bilateral deposits from individual countries to researchers.

The study shows that in a three-month period when a country receives foreign aid disbursements equivalent to 1% of its GDP, an amount equivalent to an average 7.5% of the funds received show up as deposits in tax havens. There was no equivalent rise in deposits in financial centres that were not tax havens, such as France, Germany or Sweden.

When the study looked at a subset of seven countries receiving World Bank aid equivalent to 3% or more of GDP, the level of leakage rose to 15%, whereas a larger set of 46 countries with average aid of 1% of GDP showed no statistically significant diversion of funds to tax havens.

‘This pattern is consistent with existing findings that the countries attracting the most aid are not only among the least developed but also among the worst governed’, the report says.

‘The results are consistent with aid capture by ruling elites: diversion to secret accounts, either directly or through kickbacks from private sector cronies, can explain the sharp increase in money held in foreign banking centres specialising in concealment and laundering.’

The more positive message is that among the majority of aid recipients, there’s little evidence of funds being diverted to tax havens.

However, the study notes that its estimates of leakage are conservative, as they take no account of money spent on real estate or luxury goods.

Switzerland and Luxembourg emerge as the most popular destinations for skimmed foreign aid receipts.

Switzerland has some of the strictest bank secrecy rules in the world and a share of the global market for private wealth management of around 40%. There’s evidence that as much as 90–95% of the wealth managed in Switzerland is hidden from the authorities in the owners’ home country. The study notes that other studies based on data leaks and tax amnesties have shown that offshore bank accounts are overwhelmingly concentrated at the very top of the income distribution.

The study is able to discount the hypothesis that the rise in tax haven bank deposits comes from multinational companies avoiding tax, as their deposits would be made through their subsidiary in the haven country, and would not show up as a private deposit from the aid recipient country.

The Economist says the study went through rigorous peer review from other researchers but publication was blocked by higher officials at the World Bank. It is the job of the bank’s chief economist to safeguard the integrity of the bank’s research. Goldberg, who has held the post for only 15 months, is a highly esteemed economist, and was former editor in chief for the American Economic Journal. She is returning to her former post at Yale University.

She has not commented on the controversy, and The Economist noted that her departure may also have been influenced by the World Bank’s recent appointment of former Indonesian trade minister Mari Pangestu (who is well known in Australian trade and diplomatic circles) as its head of development, which includes oversight of the economics department.

The World Bank is sensitive to any suggestions of the corrupt use of its funds, as it requires the continuing political support of its donor countries, particularly the United States. The World Bank advances loans of about US$50 billion a year on concessional terms to developing countries.

The World Bank’s president, David Malpass, who was previously under-secretary of the US Treasury and an appointee of Donald Trump, has been critical of the lack of transparency in the lending of the African Development Bank, saying it had ‘a tendency to lend too quickly and thereby aggravate the problem of country debt’.

Before taking up the post as World Bank president last year, Malpass had portrayed the institution as too big, too inefficient and too reluctant to cut lending to emerging nations such as China that had access to private financial markets. Since he took up the post, lending to China has continued, bringing criticism from the Trump administration.