Historians may come to see the American actor Alec Baldwin as US President Donald Trump’s most useful ally. Baldwin’s frequent and widely viewed impersonations of Trump on the comedy show ‘Saturday Night Live’ turn Trumpism into a farce, blinding the president’s political opponents to the seriousness of his ideology.

Of course, politicians are parodied all the time. But with Trump, there is already a tendency not to take his politics seriously. The form of those politics—unhinged tweet-storms, bald-faced lies, racist and misogynistic pronouncements, and blatant nepotism—is so bizarre and repugnant to the bureaucratic class that it can overshadow the substance.

Even those who seem to take Trump seriously are failing to get to the root of Trumpism. Democrats are so infuriated by his misogyny and xenophobia that they fail to understand how he connects with many of their former supporters. As for establishment Republicans, they are so keen to have a ‘Republican’ in office implementing traditional conservative policies—such as deregulation and tax cuts—that they overlook the elements of his agenda that upend their orthodoxies.

Part of the problem may be that Trump has come out on both sides of most major debates, championing a brand of politics that privileges intensity over consistency. This may cause Trump-watchers to dismiss attempts to establish an ideological foundation for Trumpism—such as Julius Krein’s new journal American Affairs—as hopelessly oxymoronic. But the fact that Trump is no ideologue does not mean he cannot be a conduit for a new ideology.

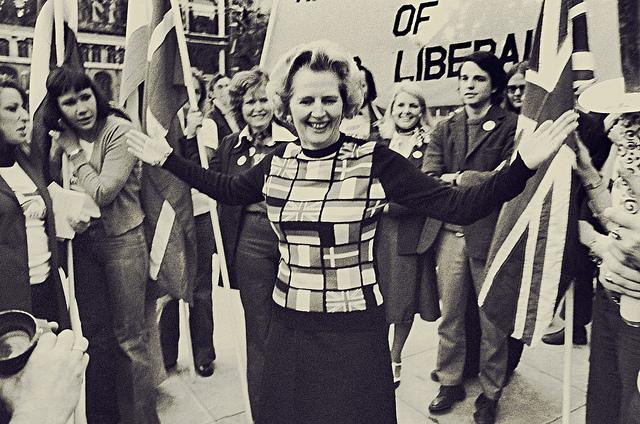

The British political establishment learned this lesson the hard way. For years, conservatives and liberals alike underestimated Thatcherism. They failed to see that behind Margaret Thatcher’s blonde hair and shrill voice was a revolutionary politics that reflected and accelerated fundamental social and economic changes.

Thatcher, like Trump, was no philosopher. But she didn’t have to be. She merely had to attract people capable of refining the ideology and policy program that would eventually bear her name. And that is precisely what she did.

Apart from those ideologues, the first to grasp the significance of Thatcher’s political project were on the far left: the magazine Marxism Today coined the term ‘Thatcherism’ in 1979. These left-wing figures saw what those in the mainstream didn’t: Thatcher’s fundamental challenge to the economic and social structures that had been widely accepted since World War II.

An editor of that magazine, Martin Jacques, who did as much as anyone at the time to provide a theoretical understanding of Thatcherism, recently explained to me why its significance was so often overlooked. ‘Political analysis at that time was very psephological and institutional,’ he said. With its focus on ‘the performance of political parties,’ he explained, it missed ‘the deeper changes across society.’

There are powerful parallels between the late 1970s and the present. Just as Thatcher recognised growing dissatisfaction with the old order and gave voice to ideas that had been languishing on the margins, Trump has acknowledged and, to some extent, vindicated the anguish and anger of a large segment of the working class who are fed up with long-established systems.

Also like Thatcher, Trump has attracted ideologues ready and willing to define Trumpism for him. Front and center is Stephen Bannon, the former executive chairman of Breitbart News, the ultra-nationalist home of the racist alt-right, who now serves as Trump’s chief strategist.

Speaking at the Conservative Political Action Conference, Bannon defined Trumpism in terms of national security and sovereignty, economic nationalism, and the ‘deconstruction of the administrative state.’ As he put it, ‘[W]e’re a nation with an economy. Not an economy just in some global marketplace with open borders.’

This reflects a fundamental conflict between Thatcherism and Trumpism: the latter aims to sweep away the neoliberal consensus of unregulated markets, privatisation, free trade, and immigration that comprised the former. But, even if the ideas are different, the tactics are the same.

To consolidate support, Thatcher would go head-to-head with carefully selected enemies—from British miners to Argentina’s president, General Leopoldo Galtieri, to the bureaucrats in Brussels. Similarly, as the Hudson Institute’s Craig Kennedy recently told me, ‘Bannon wants to radicalise the anti-Trump liberals into fighting for causes which alienate them from mainstream America.’ Every time Trump’s opponents march for women, Muslims, or sexual minorities, they fortify Trump’s core support base.

Jacques argues that the British Labour Party’s failure fully to come to terms with Thatcherism is the main reason it spent almost two decades in the political wilderness. He believes that Prime Minister Tony Blair was the first leader to recognise Thatcherism for what it was: a new ideology that upended long-held rules and assumptions. But, Jacques asserts, Blair merely adjusted to the new ideology, rather than attempting to change it.

None of this bodes well for Trump’s opponents, who are still a long way from recognising the ideological implications of his presidency. Indeed, they remain so distracted by Trump’s apparent lack of leadership skill and even mental capacity—which, to be sure, cannot compare to that displayed by Thatcher—that they have yet to grasp the depth of the divisions and neuroses that Trump has exposed.

It might be cathartic to call Trump an idiot, to laugh at his misspelled tweets and taped-up tie, but the implications of his presidency are serious. If Trump’s progressive opponents fail to engage seriously with the forces that Trump’s victory reflected and reinforced—in particular, the backlash against neoliberalism—not even impeachment will be enough to put the Trumpian genie back in its bottle.