Geography has long been a strong driver of Australia’s national security and economic planning, the oft-noted tyranny of distance a blessing and curse. And while technology and globalisation have made the world much ‘smaller’, geography seems to matter even more in this time of great-power competition.

The AUKUS announcement illustrates the seriousness of this challenge. The government’s focus on capabilities is essential, but given the reduced warning time heralded by the 2020 defence strategic update, new thinking on preparedness, resilience and sovereignty is still needed to make Australia ready for a range of contingencies.

In recent years, Australian policymakers recognised that strategic certainty was declining in the Indo-Pacific and globally. To be clear, this doesn’t mean war is inevitable. But a conflict, catalysed by operational misadventure or strategic miscalculation, is more likely than at any other time in several decades. The 2020 update provided a clear-minded assessment that we could no longer plan on having more than 10 years’ warning of a conflict. The defence strategic review (DSR) sets out broadly how Defence must respond to this challenge and again be fit for purpose, in a very different world than the Dibb review saw in the 1980s. It was encouraging to see the DSR focus on resilience and preparedness and the need for whole-of-government responses including the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade’s close involvement in this statecraft. That process should not stop with the DSR.

Until recently, much of our defence investment and capability thinking was underpinned by the notion of having at least 10 years to prepare for conflict. It’s understandable that successive governments have set a primary objective of defence investment being to create jobs, particularly to reduce the impact of the collapse of automotive industries in South Australia and Victoria.

The government expanded its demands for industry content across major programs, notably the now-cancelled Attack-class submarine. They did so to create Australian small-scale build-to-print capabilities, unfortunately often adding cost to those programs and delaying them. These initiatives were seen as politically more critical than fielding operational capability on time and at a reasonable price.

Unemployment statistics show that the South Australian economy has recovered from the collapse of car manufacturing well. Major shipbuilders are recruiting vigorously to support current build programs, and the March AUKUS announcements reveal plans for another 5,000 submarine manufacturing jobs in SA to support the AUKUS programs, with Defence focusing now on achieving a better balance between creating a scalable industry base and delivering capability faster. However, preparedness and resilience policy concerns still lag the sovereign defence industry and its manufacturing capacity issues, which is also a concern.

Programs like the submarine acquisition gather the dollars and the attention of strategists and commentators. It’s much harder to get a similar level of discourse on force posture, logistics, basing, maintenance and sustainment unless there is a public failure. The announcement that Defence’s Capability and Sustainment Group is looking to reduce sustainment costs to find additional funds for new system acquisitions will make this task even harder.

With greater uncertainty and shorter warning time, it’s crucial that Australia focus not just on big dollar projects but also on all the enabling capabilities that must be ready when needed. While not nearly as glamorous as the big capital projects, each of those major systems requires all those services to be fully effective. This policy challenge isn’t all about defence spending, and it will involve a range of public and private stakeholders. The DSR and the government’s response to it indicate that preparedness and hardening of Australia’s northern bases are a priority, backed by new investment of $3.8 billion over four years in the north, which is encouraging. Now comes the hard work of planning, organising and acting to fulfil the desired readiness and mobilisation requirements.

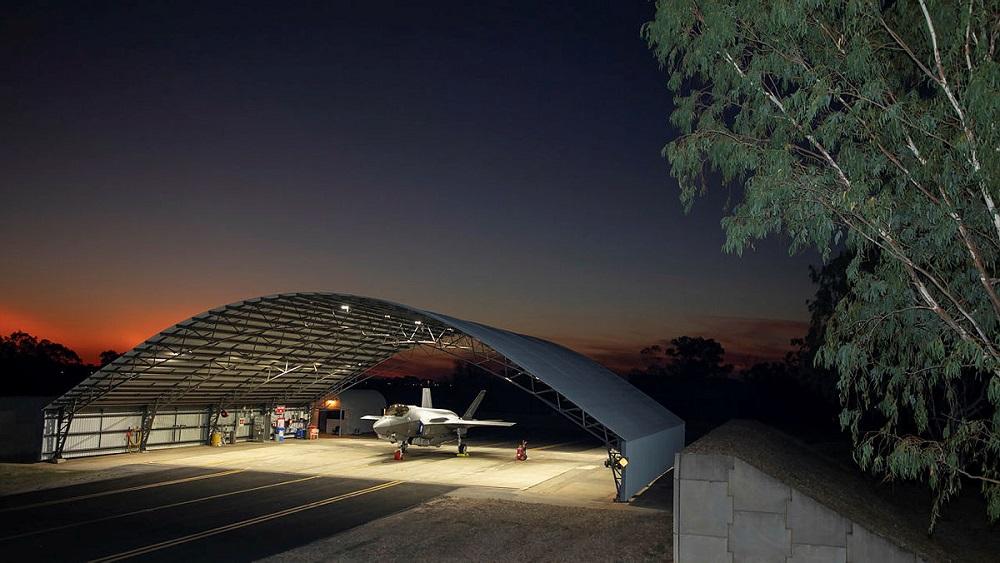

The concentration and growth of Royal Australian Air Force Base Tindal as a strategic asset is well recognised by the RAAF and the US Air Force. The USAF is committed to rotating a variety of capabilities, including strategic bombers, there and is matching this with a commitment to building and improving the base’s infrastructure. Ensuring that Tindal and Australia’s bare airbases in northern Australia are revitalised, expanded and hardened has become critical given the reduced warning time. This focus on preparedness shouldn’t stop at the front gate of these bases but must be integrated into the broader economic and infrastructure ecosystem. Getting these projects planned and delivered will require the defence organisation to engage with the NT government, construction industry, defence industry and many other stakeholders to ensure that sufficient capacity and supporting infrastructure, including housing and other civil infrastructure, is in place, staffed and operational.

Ensuring the preparedness and resilience of these bases will require more than target hardening and air defence. A more holistic approach to resilience considering transport infrastructure, supply chains (including fuel and storage capacity), network connectivity and cyber hardening, water and food sourcing and other civil defence capabilities is needed and that was recognised by the DSR’s authors. This requires close government engagement with the private sector at the federal, state and territory levels.

While identified in the DSR as critical, this whole-of-government thinking will require extensive planning, stakeholder engagement and commitment to problem solving and a sense of urgency by all involved. We must rely on more than just the nation’s capacity to mobilise in times of crisis, which has been severely tested by fire, flood and storms. The DSR was also clear that the ADF’s primary mission must be defence and defence preparedness and that significant civil disaster relief activities dilute the Australian Defence Force’s focus on its primary mission.

Northern Australia’s critical transport infrastructure has multiple single points of failure that create strategic vulnerabilities. The logistics and supply-chain networks to and from northern Australia are already subject to and stressed by weather-driven disruptions.

Northern Australia’s economy has limited market depth and surge capacity, so completing major new works requires engagement across multiple government agencies and market sectors. It also requires awareness of the coming waves of large-scale resource projects in the Territory and their massive impacts on the ‘normal’ economy and supply chains of people and products. The DSR mentions tapping into the civilian and mining infrastructures of the north. That’s commendable, but it means that energy and minerals sector players will become ‘interested parties’ and must join the planning cohorts.

The NT, like all the states and territories, has a significant housing shortage. Achieving the DSR goals will require large workforces that will need to be housed. This must be addressed as a priority.

Defence will need to assess what the force posture changes in northern Australia will require of the ADF, state and territory governments, defence industry and the construction community.

In addition to defence and minerals commitments, these demands appear likely to present serious challenges along with the need for facilities for visiting US and Japanese personnel. What happens next and how the guidance of the DSR translates into operational plans and tactics will be significant undertakings that all the stakeholders will need to support. This will require the largest mobilisation effort in Australia since World War II.

Once the details are released by Defence, the broader community including defence industry and local, state and territory governments, which are all committed to national security, defence and resilience, will mobilise their own teams to contribute to policy responses and the rollouts in the coming months and years to be ready when needed. That’s what will be required in a whole-of-government and whole-of-society response.