On 30 November, China’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs spokesperson Zhao Lijian tweeted an artist’s interpretation of the war crime allegations made against Australian special forces soldiers. The image provoked a strong response from Australian Prime Minister Scott Morrison.

The activity surrounding this tweet and on Morrison’s own Twitter account provides a snapshot of how the Chinese Communist Party’s approach to information management as a vehicle for the projection of state power plays out online. It also highlights the challenge for Australia’s own statecraft.

The CCP blocks Twitter for its citizens, but the country’s diplomats regularly use the platform to prosecute the party’s messages and narratives about topics including the Belt and Road Initiative, China’s economic recovery from the pandemic, Xinjiang and Hong Kong. They use it to address perceived double standards and slights.

Zhao, for example, is a notoriously combative tweeter and, like others in the Foreign Ministry, has spread disinformation and conspiracy theories. Diplomat Twitter is typically cagey and risk-averse, but Zhao attacks criticisms of China often by prodding at the sensitivities and internal divisions of other countries—for a domestic audience as much as a foreign one.

Of course, we don’t know how the online conversation about Zhao’s tweet would have developed had Morrison not held a press conference so soon after it was posted. However, Zhao’s tweet was designed to provoke an emotive response. It succeeded, going on to dominate multiple news cycles, and reframe coverage of Australia–China relations, momentarily distracting from the party-state’s current campaign of economic coercion and distorting arguments around human rights. Morrison’s response did create an opportunity for like-minded governments to collectively voice their disdain at Zhao’s provocation.

Zhao’s tweet is best viewed as a cross between online trolling and calculated strategic communications. It was intended to aggravate and cause controversy. The approach he took highlights a broader strategy by the party-state to contest the information environment by shaping international political discourse.

An initial examination of 349 accounts that liked Zhao’s tweet revealed 4% had been created on or after 30 November. Likewise, out of a sample of 606 accounts that retweeted Zhao’s tweet, around 3% were created on 30 November and 1 December.

As of 8 December, Zhao’s tweet has had over 18,000 retweets and 71,000 likes.

Out of the sample of accounts that liked the tweet, over 35% had zero followers and around 80% had fewer than 10 followers.

A plot of the follower network shows that these accounts tended to follow the same limited set of Chinese diplomatic accounts, US leaders, public figures and major English-language news outlets.

Some accounts that liked Zhao’s tweet showed signs of being marketing and porn accounts. One possible example had only tweeted three times, twice advertising ‘Summer Mac Essentials’ in English in 2015.

It’s not yet possible to say if the activity around Zhao’s tweet constitutes coordinated inauthentic behaviour, if it is state-directed or even if it confirms the presence of bot accounts. New accounts may have been created due to heightened political sentiment, rather than state-directed action.

However, the CCP has previously demonstrated its ability to use Twitter as part of influence operations in pursuit of its strategic goals.

In 2019, for example, ASPI examined a Twitter network that was linked by the social media company to the Chinese government. That report found the reuse of spam accounts, which are available for purchase.

Unlike the network analysed in ASPI’s Tweeting through the Great Firewall report, the unusual engagement on Zhao’s tweet has involved actual users. Many Australians responded to the thread, and the coverage of the tweet by Australian media and the responses from senior Australian political leaders have amplified the provocation.

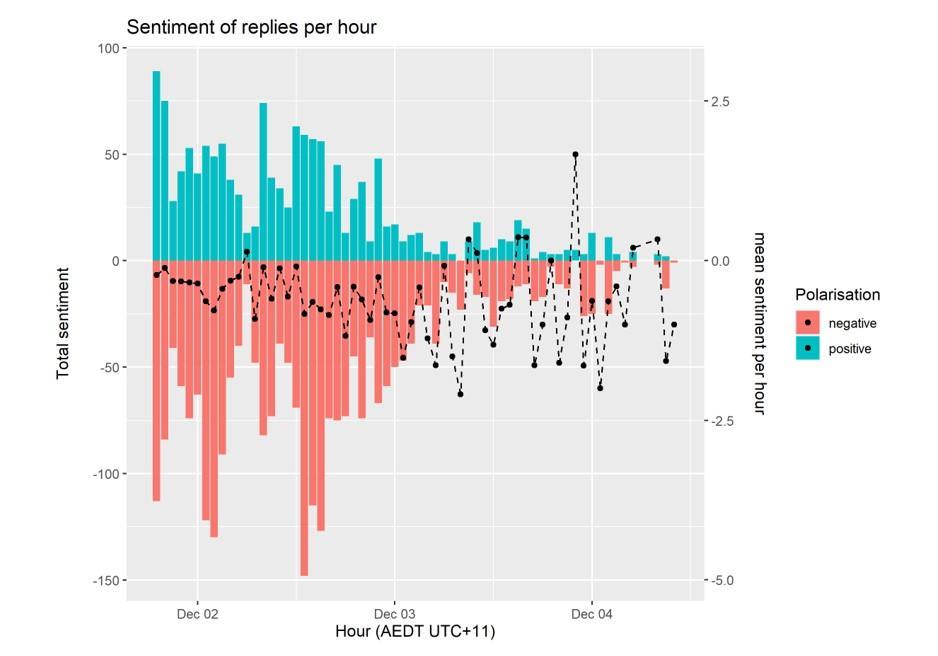

In the days after Zhao’s tweet, Morrison’s tweet about National Water Safety Day on 1 December also received an unusual amount of activity. As of 8 December, it had received at least 4,000 replies, compared with only 183 retweets and 786 likes. Looking at 2,948 replies to Morrison’s tweet, around 72% of the replies contained media, many of them provocative images.

The material being tweeted at Morrison included a ‘response’ image from the artist to the prime minister’s demand for the CCP to apologise. Other images in the replies were graphic and misleading. A photo of a grinning soldier posing with a corpse, for example, is in fact a US soldier.

Our data collection shows that more than 25% of those replying to Morrison’s tweet had zero followers; according to Timothy Graham of the Queensland University of Technology, 7% of replies he studied came from accounts created in the last month. There were also 173 accounts that had replied to both Zhao’s tweet and Morrison’s National Water Safety Day tweet.

The most commonly used words by repliers in our sample included ‘apologize’ (note US spelling) and words such as ‘hitler’, ‘picasso’ and ‘guernica’ used in reference to an image comparing Australia and fascism. The words ‘shame’ and ‘ashamed’ also featured heavily, illustrating the exchange of language used by Chinese Foreign Ministry spokesperson Hua Chunying and Morrison over which government should be ‘ashamed’.

The combination of the same repeated graphic images from Chinese artists, frequency of negative words, and unusual mass-replying by new accounts shows signs of pro-China trolling at scale. This might have been initiated authentically by frustrated and discontented Twitter users, but the timing with Zhao’s tweet shows how nationalistic trolling can be mobilised to support CCP positions.

After Zhao’s tweet, Morrison posted a message on WeChat directed at Chinese speakers that argued that the Brereton report demonstrated how a ‘free, democratic’ country dealt with such allegations.

Morrison’s WeChat post was then censored and replaced by a message that reportedly said the post used words that would ‘incite, mislead, and violate objective facts, fabricating social hot topics, distorting historical events, and confusing the public’.

In contrast, despite calls from the prime minister, Twitter has not removed Zhao’s tweet. Zhao is labelled on the platform as a ‘Chinese government account’, which offers some context and accountability for his content-sharing behaviours. While the company’s content rules are open to interpretation, there is no clear category that would justify the tweet’s deletion.

This is not just a contrast of values around free speech and content moderation. It is a perfect illustration of the CCP’s contemporary projection of political power in the information environment: a high-conflict approach to diplomacy that breaks with international norms, combined with patriotic fervour that can mobilise pro-China nationalistic responses to perceived slights, compounded by the party-state’s complete control over Chinese social media platforms, wherever their users may be.