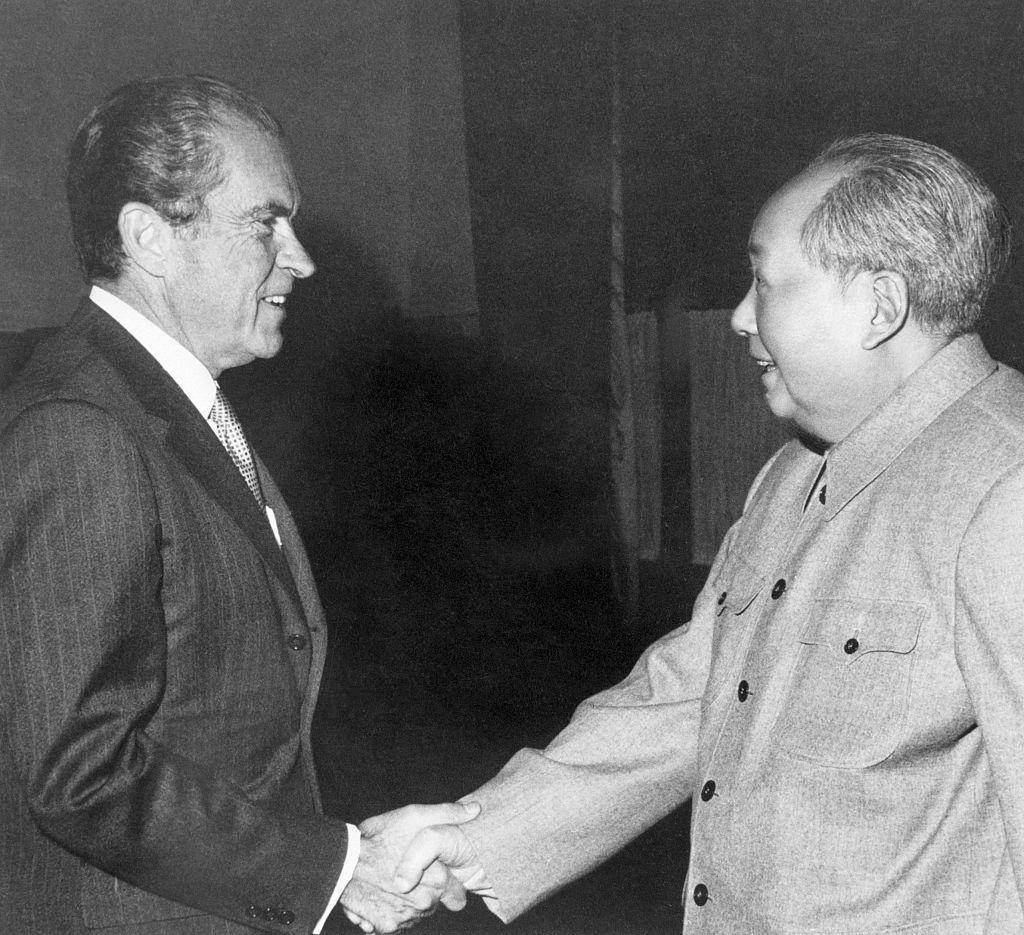

Fifty years ago this week, US President Richard Nixon visited the People’s Republic of China and met with Chinese Communist Party Chairman Mao Zedong. Nixon was the first president of the United States ever to visit China.

At the time, the US and China both needed an ally against the aggressive Soviet Union. Nixon also wanted Mao’s support for exiting the Vietnam War. And after decades of internal turmoil, Mao needed American technology to help reconstruct China.

The two heads of state met for just over an hour. However, the meeting changed the course of history, helped to accelerate China’s opening and laid the foundation for their countries’ future relationship. Nixon considered opening relations with China his greatest achievement and called his visit ‘the week that changed the world’. But even the strategically experienced Nixon could not have imagined how dramatically the world would change.

Following its establishment in 1949, for two decades China was internationally isolated, poor and ravaged by internal struggles. The Sino-Soviet rift in 1960 paved the way for an opening with the US. The turning point came in 1971, when the UN General Assembly approved the People’s Republic as China’s sole representative in the world body, in the process ousting Taiwan.

Having had no formal relations for two decades, the two countries’ first steps were tentative. Pakistan, which enjoyed good relations with both, proved the most practical channel. In October 1970, Pakistan’s President Yahya Khan conveyed to Premier Zhou Enlai a message from Nixon that the US wanted to normalise relations.

This was followed by ‘ping-pong diplomacy’, the much-publicised visit of the US table tennis team to China in April 1971, and national security adviser Henry Kissinger’s secret visit to Beijing in July.

Nixon’s visit to China followed, on 21–28 February 1972. Nixon was assisted by the legendary Kissinger, and Mao by the urbane Zhou.

The meeting with Mao was held on the first day, in the chairman’s study. Kissinger describes the discussion as wide-ranging, including building relations, Taiwan, and a US withdrawal from Vietnam. Mao left Nixon and Zhou to work out the details. That time there was no second meeting, apparently due to Mao’s poor health.

The visit resulted in the Shanghai Communiqué in which the US recognised the one-China policy. The visit had repercussions around the world. America’s Asian allies were concerned, since most had defence agreements with the US. Taiwan was worried about its special status, and Tokyo went into shokku. The greatest shock, however, was in Moscow, which had warned the US not to take advantage of the Sino-Soviet split, and quickly agreed to a bilateral summit with Washington.

According to the Canadian historian Margaret MacMillan, Nixon wanted to bring stability to Asia. Kissinger goes a step further, suggesting that Nixon wanted a more peaceful world order.

Once Deng Xiaoping in 1978 announced that China would open its economy, the West expected broader change. The assumption was that growth would bring affluence, and that China’s middle class would expand, increasing pressure for democracy. Gradually—so the optimists thought—China would join the rules-based international order.

Initially, change was in the air. Beijing joined the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank and set up special economic zones, and foreign funds started to flow. For two decades, Washington used democratisation to justify its support for China’s economy. From 1980, the US annually granted China most-favoured-nation status, and few restrictions were placed on technology transfers.

However, two events intervened: the violent suppression of the Tiananmen Square pro-democracy demonstrations in 1989 and the collapse of the Soviet Union two years later. The Tiananmen incident led to the ousting of the reform-minded CCP General Secretary Zhao Ziyang, with power shifting to Premier Li Peng’s hardline conservatives. Economic reforms stalled.

The collapse of the Soviet Union deeply shocked the CCP and led to a thorough-going internal review. To avoid a similar fate, the party reformed its structures and strengthened internal discipline. Its plans are currently implemented by 95 million carefully selected cadres.

Within two years of Tiananmen, President George H.W. Bush once again granted China MFN status, and in 2001 China was let into the World Trade Organization.

If Nixon and his successors had in a crystal ball seen China’s rapid emergence as a rival superpower, would they have supported China as openly as they did?

University of Chicago professor John Mearsheimer has long criticised American support for China. He wonders why four presidents, George H.W. Bush, Bill Clinton, George W. Bush and Barack Obama, all proactively helped to strengthen China, although this was at odds with the United States’ natural geopolitical interest of retaining its position as the world’s leading superpower.

Of the four key participants in the Nixon–Mao meeting, only the 98-year-old Kissinger is still alive. According to him, in 1972 Nixon could not have imagined a world in which the Soviet Union had collapsed, China had risen to its present stature, and the US and China were on the brink of a new kind of cold war.

In a 2021 speech at the McCain Institute, Kissinger warned of the apocalyptic risks facing the world if war were to erupt between the US and China. The American and Chinese military arsenals are far more destructive now than those of the Cold War, in particular given the role of artificial intelligence. And China is affluent, which the Soviet Union never was.

Fifty years on, this sounds almost like an admission from Kissinger that he helped Nixon to open Pandora’s box.