Almost inadvertently, US energy security has been threatened by a ransomware attack which demonstrated dramatically how the consequences of such hacks are escalating.

This one probably won’t be the worst, but it will change the way governments respond to ransomware.

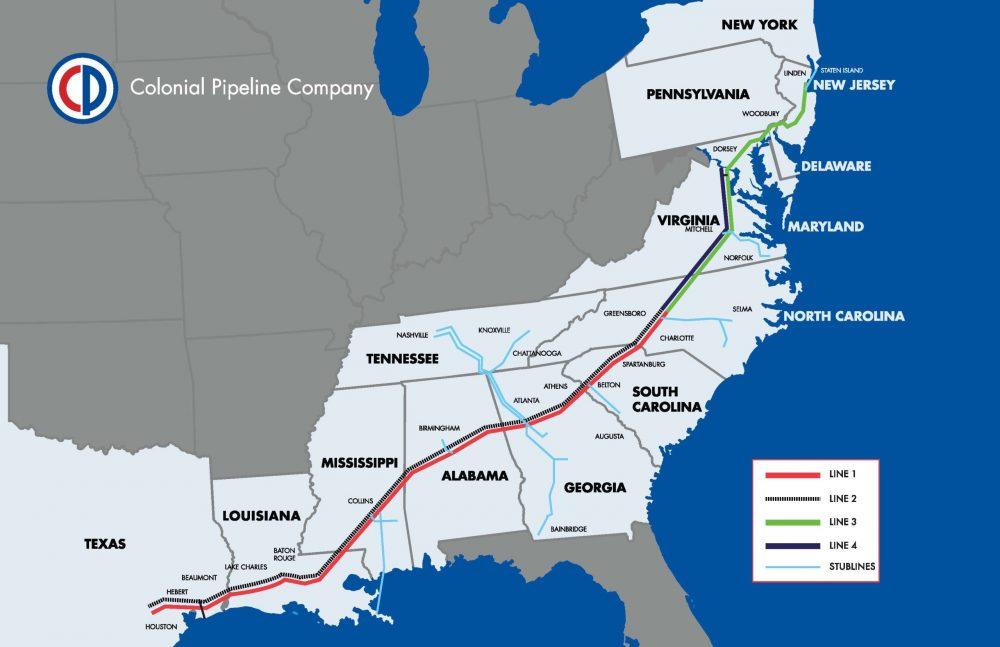

Colonial Pipeline carries gasoline, diesel and jet fuel from Houston to New York, with an array of branch lines servicing states across the eastern seaboard of the US. On Saturday 8 May Colonial announced that it had been the victim of a ransomware attack and that to contain the threat it ‘proactively took certain systems offline’, which ‘temporarily halted all pipeline operations’.

In a sense that highlights critical infrastructure’s vulnerability. The halt to pipeline operations was entirely unintended by those who carried out the ransomware attack and the operational disruption was ‘collateral damage’.

The hackers did not target the pipeline’s industrial control systems to deliberately stop the flow of oil. Colonial itself shut down systems to prevent further spread of malware. This disruption would likely have been far worse had the group intended to disrupt the pipeline.

As the shutdown continued over several days, petrol prices surged, service station queues lengthened, customers hoarded fuel as pumps ran dry and the US Consumer Product Safety Commission warned people to ‘not fill plastic bags with gasoline’. The US Department of Transport temporarily loosened road transport rules to allow more road-based shipment of fuel as concern over shortages escalated within government.

Map of the Colonial Pipeline network.

By Monday 10 May, the FBI announced that DarkSide ransomware was responsible for the Colonial hack.

DarkSide operates on a ‘ransomware as a service’ business model, providing centralised services that their ‘affiliates’ can use to extort money from victim organisations. The affiliates conduct the operations, but DarkSide receives a 10–25% cut of the ransom. Services fundamental to running ransomware operations include payment servers, encryption and decryption tools to lock and unlock victim data, and a blog to claim responsibility, advertise hacks and pressure companies.

But beyond ransomware, DarkSide affiliates also steal data and threaten to leak it. As victims with good backups may still be motivated by the threat of sensitive data being leaked, this second method of extortion is increasingly common among ransomware gangs. In these instances, DarkSide would collect and store victim data on staging servers.

Other services were even more innovative. It appears that DarkSide was also willing to let paying customers know when they’d hacked publicly listed companies ahead of their blog announcements, presumably so they could short sell stocks ahead of the news of a ransomware attack.

While they were developing a portfolio of extortion tools and tactics, DarkSide was also attempting to manage its reputation to avoid attracting law enforcement attention. It stated that it would not attack medical facilities, schools and universities, non-profits, governments and the funeral sector.

There’s good evidence that the criminals are Russian. They recruit Russian-speaking affiliates and advertise on Russian language forums, they don’t attack the former Soviet republics of the Commonwealth of Independent States and their malware won’t attack devices with Russian language settings.

In the aftermath of the Colonial Pipeline hack, DarkSide issued a statement saying:

We are apolitical, we do not participate in geopolitics, do not need to tie us with a defined government and look for other our motives. Our goal is to make money, and not creating problems for society. From today we introduce moderation and check each company that our partners want to encrypt to avoid social consequences in the future.

In part this seems to be an attempt to distance DarkSide from the Russian government; parts of Eastern Europe and Russia are a permissive environment where cyber criminals are tolerated, but if gangs start to cause geopolitical problems local law enforcement could suddenly become motivated to act.

And diplomatic pressure is being applied. US President Joe Biden said that although he didn’t believe the Russian government was involved, the criminals were Russian. ‘We have been in direct communication with Moscow about the imperative for responsible countries to take decisive action against these ransomware networks,’ Biden said.

Within a day of discovering the attack the CEO of Colonial Pipeline had decided to pay the ransom, saying later that ‘it was the right thing to do for the country’. The pipeline returned to full operation within the week, although the decryption tool was reportedly so slow that Colonial continued to restore from backups.

Paying ransoms is clearly undesirable from a public policy point of view—it encourages further ransomware attacks and funds the evolution of the ransomware ecosystem. Yet at the same time ransom negotiations will settle on a price where the cost–benefit of paying can be justified and there are many situations where payment is clearly in the best interests of stakeholders.

But cyber insurance should not be used to pay ransoms. Unlike many other types of insurance, cyber insurance deals with a human adversary and the threat is rapidly evolving. Current practice is a vicious circle where insurance payouts encourage and fund improved ransomware which extracts more insurance payouts. Perversely, ransomware hackers will search for their victims’ insurance policies and then use the insured amount to set ransom demands.

In total, DarkSide appears to have extracted at least US$90 million in ransoms since August, and more than US$9 million in the month of May alone. That was made up of US$4.4 million from a chemical distribution company and US$5 million from Colonial Pipeline. With increasing attention—Biden said the US would ‘pursue a measure to disrupt their ability to operate’—the sum seems to have been enough for the hackers.

The day after Biden’s statement the DarkSide hackers said they’d lost access to their infrastructure including their blog and payment servers and would be shutting their service. Lightning-fast US retaliatory action seems unlikely given the time required to prepare for a cyber operation, and the DarkSide crew may simply have taken the money instead of paying their affiliates.

In the short term, DarkSide may have disappeared but, given the sheer volume of money available, other criminals will fill the void. Beyond improving defences, this story also shows that a promising approach is to focus on the ransomware ecosystem and its incentives.

DarkSide and similar groups actively try to avoid law enforcement attention and minimise associations with the state in which they operate. Western nations need to align diplomatic, intelligence and law enforcement efforts to make it much harder for ransomware crews to operate with impunity.