Forced labour and the abusive practices of the ‘re-education camps’ in China’s Xinjiang region are being exported to major factories across the country, implicating both global brands and the hundreds of millions of consumers (including here in Australia) using their products.

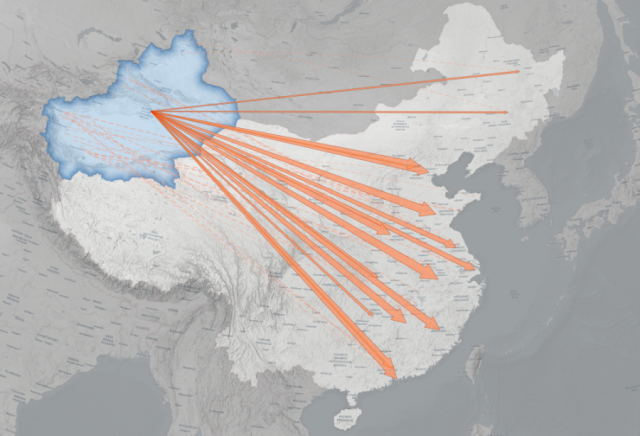

Our new ASPI report reveals that the Chinese government has facilitated the mass transfer of Uyghur and other ethnic minority citizens from Xinjiang to factories across China. Between 2017 and 2019, our report estimates that at least 80,000 Uyghurs were transferred out of Xinjiang and assigned to factories through labour transfer programs under a central government policy known as ‘Xinjiang Aid’.

Figure 1: Uyghur transfers to other parts of China from 2017 to 2020

Source: ASPI’s International Cyber Policy Centre, which used a range of data sources, including local media reports and official government sources.

Under conditions that strongly suggest forced labour, Uyghurs are working in factories that are in the supply chain of more than 80 well-known global brands in the technology, clothing and automotive sectors, including Apple, BMW, Calvin Klein, Dell, Fila, Gap, Huawei, H&M, Nike, Samsung, Skechers, Sony, Victoria’s Secret and Volkswagen.

One factory that received Uyghur workers in July 2019 lists CRRC—the Chinese state-owned rail manufacturer currently building trains for the Victorian government—among its customers.

Strikingly, local governments and private brokers are paid a price per worker by the Xinjiang provincial government to organise the labour assignments. Some factories appear to be using Uyghur workers sent directly from ‘re-education’ camps, and the threat of detention hangs over any minority citizen who doesn’t want to comply with their government-sponsored work assignment.

It is impossible to confirm whether every citizen transferred for work from Xinjiang is coerced, but the cases where sufficient detail was available showcase highly disturbing forced labour practices.

In these factories far from home, Uyghur workers are typically forced to lead a harsh, segregated life under so-called military-style management. They undergo organised Mandarin and ideological training outside working hours, are subject to constant surveillance, and are forbidden from participating in religious observances. Numerous sources—including government documents—show that transferred workers are assigned government minders and have limited freedom of movement.

The surveillance component of this state-sponsored labour transfer scheme is extensive, and constitutes, we think, an underestimated but significant indicator of forced labour. Chinese authorities and factory bosses manage these Uyghur workers by tracking them both physically and electronically.

One provincial government document describes a central database, developed by Xinjiang’s Human Resources and Social Affairs Department and maintained by a team of 100 specialists in Xinjiang, that records the medical, ideological and employment details of each labourer.

The database incorporates information from social welfare cards that store workers’ personal details. It also extracts information from a WeChat group and an unnamed smartphone app that tracks the movements and activities of each worker.

In some cases, local governments in Xinjiang send Chinese Communist Party cadres to simultaneously surveil workers’ families back home in Xinjiang— a reminder to workers that any misbehaviour in the factory will have immediate consequences for their loved ones and further evidence that their participation in the program is far from voluntary.

Political indoctrination is a central part of these labour transfers. In a large factory making shoes for Nike in Qingdao, Shandong province, there’s a purpose-built ‘psychological dredging office’ where minority workers are counselled by Han and Uyghur cadres, and their ideology and behaviour are closely watched. These offices are also present in Xinjiang’s ‘re-education’ camps.

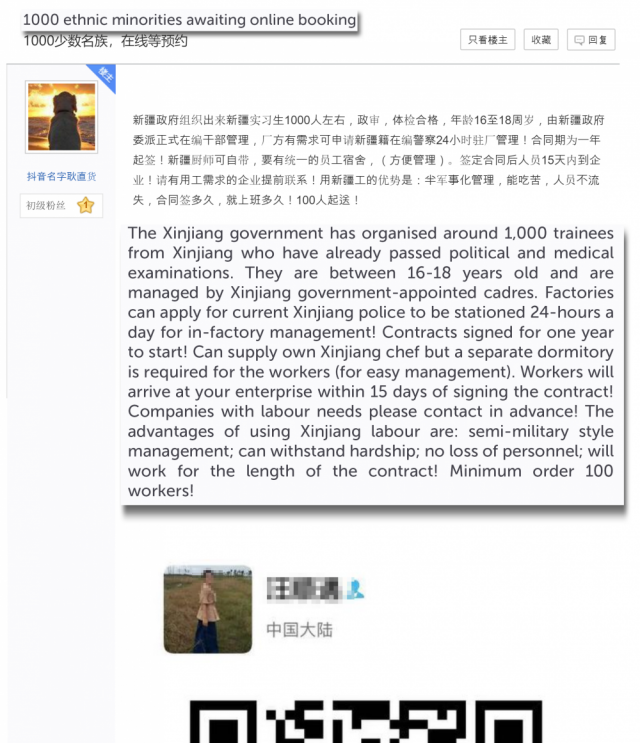

In recent years, advertisements for ‘government-sponsored Uyghur labour’ began to appear online. Some of these advertisements provide insights into the terms and conditions under which some of these forced transfers of workers are occurring, including minors. One ad offers ‘batches’ of 16- to 18-year-old Uyghur workers, with ‘semi-military style management’ and stipulates ‘minimum order 100 workers’.

Figure 2: Labour-hire advertisement offering young Uyghur workers under ‘semi-military style management’

Source: ‘1,000 minorities, awaiting online booking’ (1000少数民族,在线等预约), Baidu HR Forum (百度 HR吧), 27 November 2019. Translated from Chinese by ASPI.

The business of ‘buying’ and ‘selling’ Uyghur labour can be quite lucrative for local governments and commercial brokers, especially if they are transferred outside of Xinjiang. According to a 2018 Xinjiang provincial government notice, for every rural ‘surplus labourer’ transferred to work in another part of Xinjiang for over nine months, the organiser is awarded Ұ20 (US$3); however, for labour transfers outside of Xinjiang, the figure jumps 15-fold to Ұ300 (US$43.25).

Receiving factories across China are also compensated by the Xinjiang government, including a Ұ1,000 (US$144.16) cash inducement for each worker they contract for a year, and Ұ5,000 (US$720.80) for a three-year contract. The statutory minimum wage in Urumqi, Xinjiang’s regional capital, was Ұ1620 (US$232.08) a month in 2018.

Labour transfers have been used by the Xinjiang government for years, but we found evidence they have increased in popularity since the ascension of hardline Xinjiang Party Secretary Chen Quanguo in 2014, and particularly since the start of the crackdown on Uyghurs in 2017. Pitched as a poverty alleviation mechanism, they appear to be an increasingly important political priority for the government and are intertwined with the ‘re-education’ campaign designed to forcibly assimilate Uyghurs and other minority citizens into the Han majority.

Our report contains an appendix with full citations that details 35 of these labour transfer programs, and the factories and dozens of global brands linked with them.

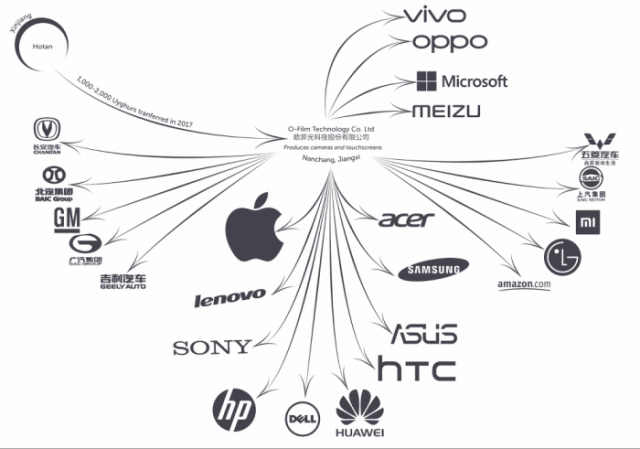

It also contains supply-chain charts that visualise some of these relationships. O-Film Technology Co. Ltd, for example, manufactured the ‘selfie cameras’ for the iPhone 8 and iPhone X and it also manufactures camera parts and touchscreen components for technology giants including Huawei, Lenovo and Samsung.

Figure 3: O-Film supply chain

Source: ASPI’s International Cyber Policy Centre; see appendix to report for supply chain information.

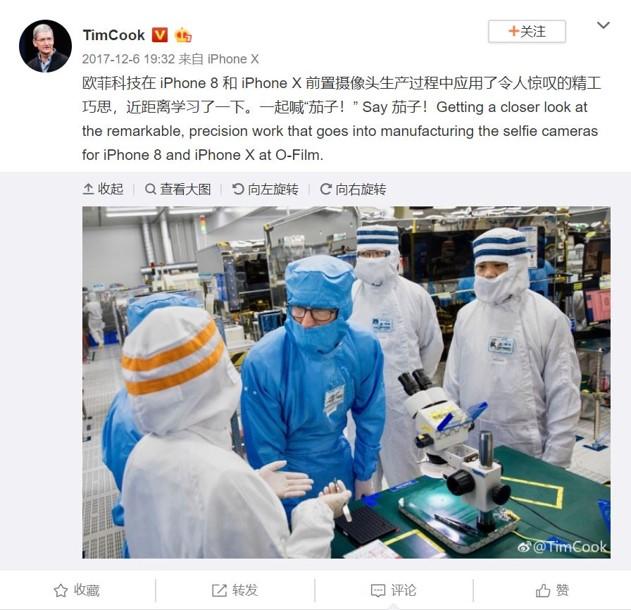

In December 2017, Apple’s CEO Tim Cook visited O-Film’s Guangzhou factory—and posted a picture of himself there on the Chinese social media platform Weibo. Earlier that year, between 28 April and 1 May, 700 Uyghurs were reportedly transferred to work at another O-Film factory in Jiangxi province where they were managed by minders and expected to ‘gradually alter their ideology’ and ‘understand the Party’s blessing, feel gratitude towards the Party, and contribute to stability’, according to a local media report.

Figure 4: Tim Cook’s Weibo post from O-Film’s Guangzhou factory in December 2017

Source: ‘Apple CEO Cook tours O-Film Technology Co. Ltd: iPhone X/8 selfie screams “cheese”’, IT Home, 6 December 2017; the original Weibo post can only be accessed with a Weibo login.

The Chinese government should uphold the civic, cultural and labour rights enshrined in China’s constitution and domestic laws, end its extrajudicial detention of Uyghurs and other Muslim minorities in Xinjiang, and ensure that all citizens can freely determine the terms of their own labour and mobility.

Companies whose supply chains are using forced Uyghur labour could find themselves in breach of international and domestic laws that prohibit the importation of goods made with forced labour or mandate disclosure of forced labour supply chain risks. The companies listed in our report should conduct immediate and thorough human rights due diligence on their factory labour in China—across their supply chains—including robust and independent social audits and inspections. It is vital that through this process, affected workers are not exposed to any further harm, including involuntary transfers.