As the curtains fell on the UN’s annual high-level meetings last week, the world was left with an unsettling message: the international order is crumbling, and no one can agree on what comes next.

The focus of the week—the one time of the year that most of the world’s leaders are all in the same place—was meant to be on urgently accelerating global action on the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development.

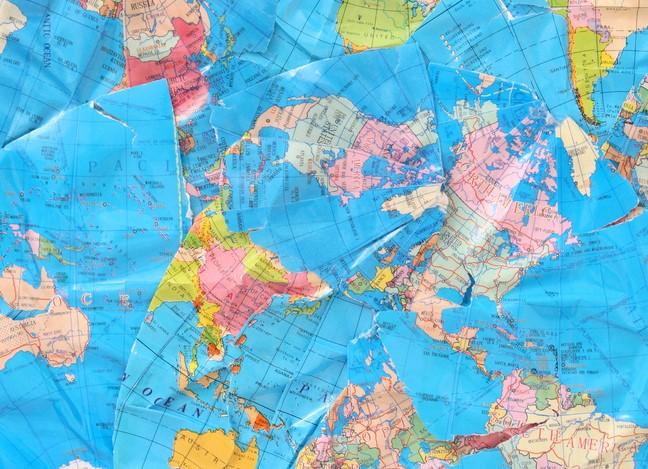

Yet, against a backdrop of intensifying geopolitical tensions, the war in Ukraine, coups in Africa, the escalating climate crisis and the ongoing pandemic, a different theme emerged: the fracturing and fragmenting of the global order, and the urgent need to reform the United Nations before it’s too late.

Secretary-General Antonio Guterres’s opening address to the UN General Assembly was both a rallying cry and a stark warning: ‘Our world is becoming unhinged. Geopolitical tensions are rising. Global challenges are mounting. And we seem incapable of coming together to respond.’

Describing a world rapidly moving towards multipolarity while lamenting that global governance is ‘stuck in time’, Guterres warned that the world is heading for a ‘great fracture’. Urging the renewal of multilateral institutions based on 21st-century realities, he left no illusions about what will happen if this doesn’t happen: ‘It is reform or rupture.’

Unsurprisingly, Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky echoed this in a powerful address to a special UN Security Council high-level open debate later in the week. He warned that the gridlock over Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in the UN meant that humankind could no longer pin any hopes on it to maintain peace and security. He then called for meaningful reform—including on the use of the veto in the UN Security Council.

It’s a sentiment shared by Australian Foreign Minister Penny Wong. In her address to the UN Security Council, she called for urgent reform, including ‘constraints on the use of the veto’. She condemned Russia’s use of its position as a permanent member of the Security Council to veto any action ‘as a flagrant violation of the UN charter’, and later told the media that ‘across many issues, the UN system is falling short of where we want it to be and where the world needs it to be, but what we want to do is to work with others to ensure that the United Nations evolves’.

While the existence of the veto prevents any Security Council action from being taken against Russia for its invasion of Ukraine (or against the other four permanent members), the UN charter more broadly—by design—makes any reform of the UN incredibly difficult and extremely unlikely. And given that US President Joe Biden was the only leader of a P5 country to actually show up to the UN for leaders’ week, it’s not clear that even Western countries like the UK and France are committed to the UN—the bedrock of the international system since World War II.

Where does all this leave a multipolar world teetering on the brink? With the existing order already so divided, how do we reimagine and agree on a global system that can meet the challenges of the 21st century?

After all, if, despite being a blatant breach of international law and the UN charter, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine hasn’t caused any meaningful reform to yet take place, what will?

Indeed, the fact that the broader international community is relatively ambivalent about holding Russia to account for its ongoing atrocities in Ukraine is a testament to Russia’s and China’s efforts to dilute multilateral institutions and create an alternative world order that’s more accommodating of autocracies.

Confronted with these dynamics, the international community stands at a pivotal juncture. The decisions made now will determine the trajectory of the global order for decades to come. As Guterres said in his opening address, the international community is presented with a stark choice: reform and rally behind a renewed vision of multilateralism, crafted collaboratively to meet the multifaceted existential challenges of our times; or continue to pursue self-interest above all else, and prepare for a rupture.

By the looks of things, in this rapidly changing landscape marked by division and lack of consensus, we must steel ourselves for what lies ahead: an era of ‘unhinged’ global disorder.