Recent events, rumours and reports have cast a light on the future of Australia’s defence industry. High-profile considerations have centred on shipbuilding and submarines with the ongoing Senate Economics References Committee Inquiry, ministerial and prime-ministerial positioning for a ‘Japanese solution’ to Australia’s future submarine, and the ongoing debate about costs and economic benefits.

But it’s also important to step back and consider the future of the broader industry. What’s the current status of the local defence industry? How does it compare with that in other jurisdictions? Is defence-related industry intrinsically different to other sections of the economy? Where are we headed, and is that a good place?

If we take those questions in reverse order it’s clear we don’t know where we’re headed. We’re on a mystery tour and no-one seems to care where it might end. Will it be possible to come back? Decisions on military acquisitions and support seem to be made on the basis of the balance sheet rather than any deeper consideration of strategic importance. Repeatedly, statements are made that the ADF needs to get the best capability for the available money, and that defence isn’t a job-creation programme. At face value both of those statements are sound, but they don’t take into account the longer-term ramifications of in-country industrial activity able to support the defence force.

Some suggest there’ll be more jobs in Australia because there’ll be more submarines, for example. What jobs? How does such an outcome equate with the smart manufacturing and high-technology economy that successive governments have preached but not practised? Is digging twice as many ditches satisfactory when someone else is making all the ditch-digging equipment?

Working back up the line of questioning there are fundamental differences between defence industry and other aspects of the economy—just as there are between those in uniform and those in civilian life. Defence industry is there to support the people in the services who may have to put their lives on the line for the protection of the nation. Few in society are called upon to do that.

Defence industry’s there to ensure that if (or when) that happens those people have the right equipment, and that it’s fit for purpose, properly maintained, and can be repaired and upgraded as and when needed. Defence capability and industry isn’t just an entry on a balance sheet. The question needs to be asked—repeatedly—whether Australian industry should do that, and also whether it can, or can’t. The question also needs to be asked whether the decisions being made harm the ability of the local industry to support the military in the field. Let’s face it—no-one else is going to care about Australia’s military as much as Australians.

How do we compare with other countries? Quite simply, abysmally. Most countries that fancy themselves as middle powers support their defence industry (see here, here, here, here and here). They see value in doing defence-related activities, particularly the support and upgrade of military capability, in country. They put a premium on the development and retention of local skills. They see a link between indigenous defence-industry capability and the mitigation of strategic and sovereign risk. It appears we don’t. What makes Australia so different that we’re happy off-shoring our industrial defence capabilities? Why do we naively believe that it doesn’t matter, that it isn’t worth the investment, and that someone else will pick up the pieces for us? That’s not sensible. You wouldn’t blithely expect someone else to protect your house when you can’t be bothered to do it yourself—or you want to save a few bucks.

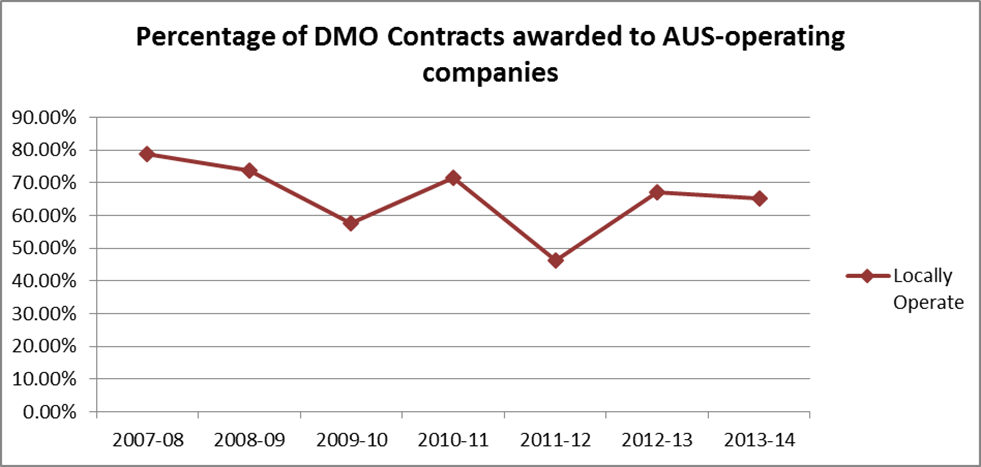

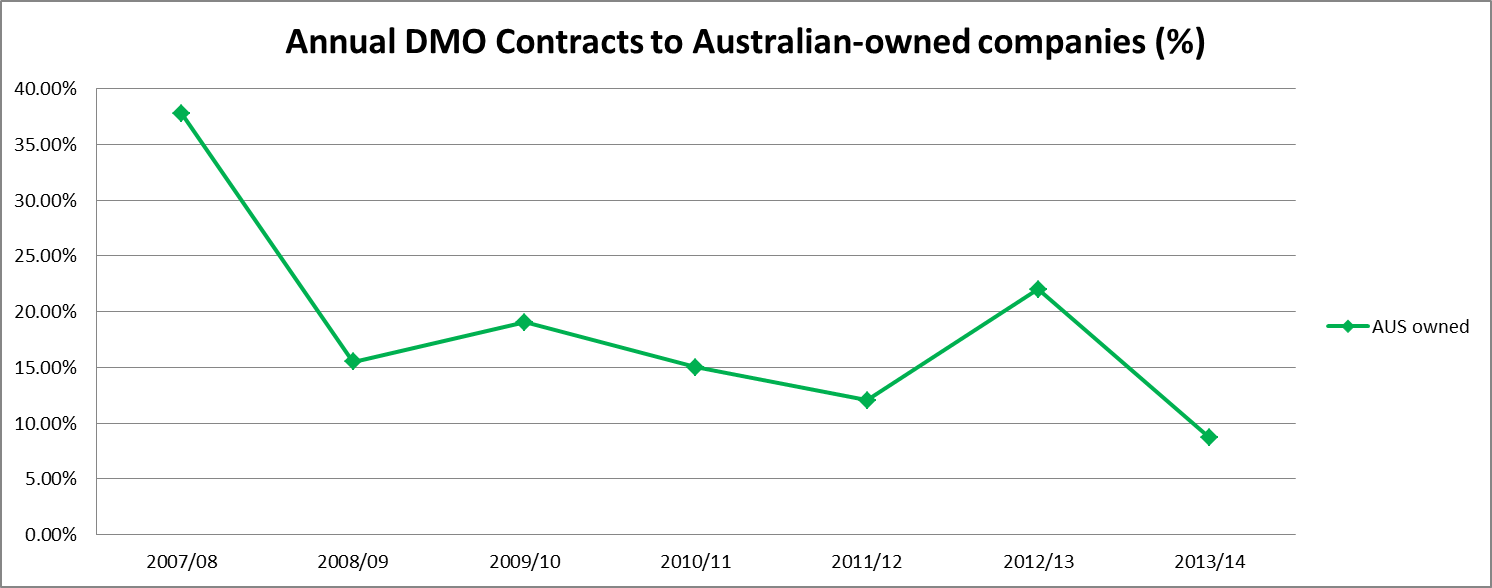

And now for the reality check. What’s the status of local defence industry? Put simply it’s not good—and getting worse. The percentage of contracts being placed into Australia is declining—even to the onshore offshoots of overseas companies. Analysis of the Government’s own data from Austender for contracts placed by the Defence Materiel Organisation (DMO) over the past seven years shows that to be the case. When the data for Australian-owned companies is separated from the other contracts the results are pitiful. The following graphs (click to enlarge) show that to be the case (and remember this is the Government’s own data). True, it’s contract data—not cash-flow data—but it’s difficult to have cash flow without a contract.

Why are we happily ‘off-shoring’ our defence industrial capability with no consideration of what that might mean in the long term just because it looks good on a balance sheet?

Why are we heading blindly along a path when nobody can articulate where we’re going, or what is might look like when we get there?

Why should we blindly accept the inherent contradiction between the current industrial position and the DWP 2013 statement that ‘The highest priority ADF task is to deter and defeat armed attacks on Australia without having to rely on the combat or combat support forces of another country’? The fact that we’ll need to rely on the industrial support of another country (or countries) either escapes attention, or isn’t considered relevant.

We need to get our heads out of the sand, to consider the bigger picture beyond the accountants’ numbers, and to build towards the defence-industry capability that we need. We need to mitigate our own strategic risks, and address our own sovereignty—then we might finally be a middle power and not just a pretender.

Graeme Dunk is manager of Australian Business Defence Industry, a national defence industry association.