I write this article from Wadi Rum Desert, Jordan. Instead of stiffly sitting at my ergonomic desk, I’m reclined in a camel-skin tent. My phone lies forgotten in my backpack (there’s no reception here). I look out my window, not to rest my eyes from all the screen time, but to watch a herd of wild camels wander by.

Maybe I’ve been away from home too long and I’m having my ‘Lawrence (or Harriet) of Arabia’ moment, but as a cybersecurity professional I can’t help but use this time to reflect on the impact of technology. And I don’t just mean my inability to google synonyms for this article. Back home, my personal and professional lives revolve around the artificial intelligence side of technology and innovation—developing it, talking to colleagues about it, boring my friends with stories about it.

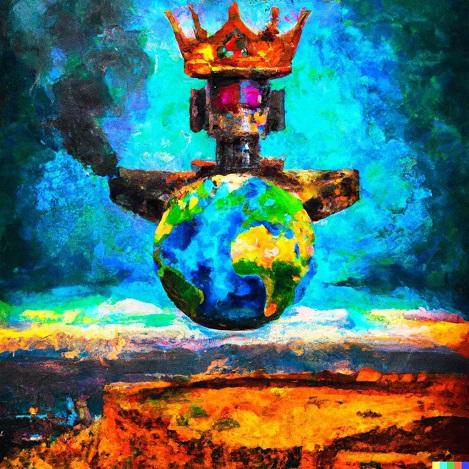

In the academic world, the pace of AI development is staggering. OpenAI’s DALL-E model can generate incredibly authentic images from just a few words of text (see below for an image created by my prompt: ‘an artificial intelligence taking over the world as an oil painting’). Meta’s No Language Left Behind model can translate 200 languages, including Igbo and Assamese, which have previously been ‘left behind’ due to lack of training data. OpenAI’s Codex model can even generate computer software programs based on text instructions.

Now AI is not just a technological novelty, but a strategic priority for every country with the resources to invest in it. AI dominance is a goal of the United States, China and Russia, and some reports assert that whoever achieves AI dominance in the next few years will ‘rule the world’.

We’ve already seen the introduction of policies that seek to control this new theatre. Last month, the US announced new export controls aimed at choking China’s access to AI and semiconductor technologies. Closer to home, Australia is developing partnerships geared at AI collaboration, through bilateral mechanisms such as the comprehensive economic cooperation agreement with India and multilateral groupings like the Quad partnership with Japan, India and the US.

Now, how does all of this relate to Wadi Rum?

Spending a few days cut off from technology but very much in touch with human experiences—learning about Wadi Rum from the Bedouins, and meeting other travellers from around the world, with all sorts of backgrounds and careers and views on technology and innovation—prompted me to question my own assumptions. In particular, I started to reflect on why we invest in AI at all and who benefits from it.

During a brief stint at Stanford University in 2018, I was fortunate enough to be exposed to the global epicentre of innovation, Silicon Valley. Almost everyone I spoke to told me how they were about to change the world through AI. However, I came to realise that when people talk about changing the world, their definition is a little small. Most of the time it was the developed world, the digital world, the US or Silicon Valley. And I came to question what exactly they were trying to change, and why.

When it comes to AI, a chatbot that can’t be differentiated from a human agent is really cool, but who is it benefiting? Is it just a company’s profit margin? UN reports increasingly highlight that the growing digital divide is actually worsening inequality around the world.

As AI increasingly becomes a tool for international politics, I strongly believe we need to consider how we ensure its development and its execution are safe, secure and ethical.

AI has known technical challenges, such as how to safely deploy it so that it doesn’t become biased—for example, sexist, racist or homophobic—over time. From a strategic lens, there are also issues to overcome in terms of the level of autonomy these systems can be granted, when and how to delegate decisions to humans, and whether this should be legislated. Australia’s Centrelink Robodebt scandal and the international debate over lethal autonomous weapons are examples of this balancing act.

AI also has known security issues, demonstrated by how these systems have been shown to be vulnerable to attack through adversarial machine learning. Inference attacks can cause leaks of sensitive data used in the model training process, or the decisions models make may be incorrect due to evasion attacks. Their use for security purposes is also of strategic consequence—threats over AI capabilities are increasingly being used as political instruments, for example.

The ethical application of AI overarches both of these concerns. The ability for AI to perform object detection with great accuracy is technically impressive, but does that mean it’s ethical to use these systems to perform facial recognition and surveillance? And while AI use may raise the share prices of some of the world’s richest companies, the first steps in technological dominance are not necessarily about making systems more intelligent, but about securing the systems we already have, as evidenced by the recent data breaches of Optus and Medibank. Also, many people in the developing world still lack an internet connection, limiting their access to the opportunities afforded by tools like online banking and the digital economy.

Philosophical differences in the deployment of AI between countries are amplifying an already tense geostrategic environment. However, technology, even one as impressive as AI, is not a substitute for diplomacy. Good diplomacy is more important now than ever.

As I discuss these topics with my fellow travellers, drinking tea and watching the sunset over the stunning rock formations that Wadi Rum is so famous for, I notice we all have different perspectives and answers to these challenges. So does everyone I discuss these issues with professionally. This confirms why it’s so important to intensify the international dialogue around AI and continue discussing common tools, philosophies and standards for its use as both a technical and strategic tool. But for now, I’m going to enjoy my last few moments of technological isolation, because a good conversation with a real human and a beautiful sunset trump an AI-generated fabrication every time.