Recent India–Pakistan border skirmishes have brought the dispute over Kashmir to the world’s attention once again. While the latest crisis has abated for now, the issue still festers and is likely to lead to more clashes between these two nuclear-armed nations.

It’s important to understand the historical, political and ideological dynamics in play in Jammu and Kashmir because the crossroads that India and Pakistan currently find themselves at is the same one that’s bedevilled their relationship since 1947. Pakistan alleges that India’s ‘control’ of Kashmir is illegal and that the Indian government is brutally quashing the Kashmiris’ right to self-determination; India argues that Jammu and Kashmir is an integral part of the country. The roots of this conflict lie in the partition of the Indian subcontinent along religious lines by the departing British rulers in the late 1940s.

The princely state of Jammu and Kashmir was an anomaly in the logic of the partition: it was a Muslim-majority state governed by a Hindu ruler. Even as the maharaja dithered about joining India or Pakistan or remaining independent, the Pakistan Army dispatched a band of guerrilla raiders, who infiltrated Kashmir in October 1947. The maharaja appealed to Indian Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru, who made New Delhi’s intervention conditional on Jammu and Kashmir’s acceding to the Indian Union. The maharaja signed an instrument of accession to India in October 1947, and Indian armed forces thwarted the advance of the Pakistani infiltrators.

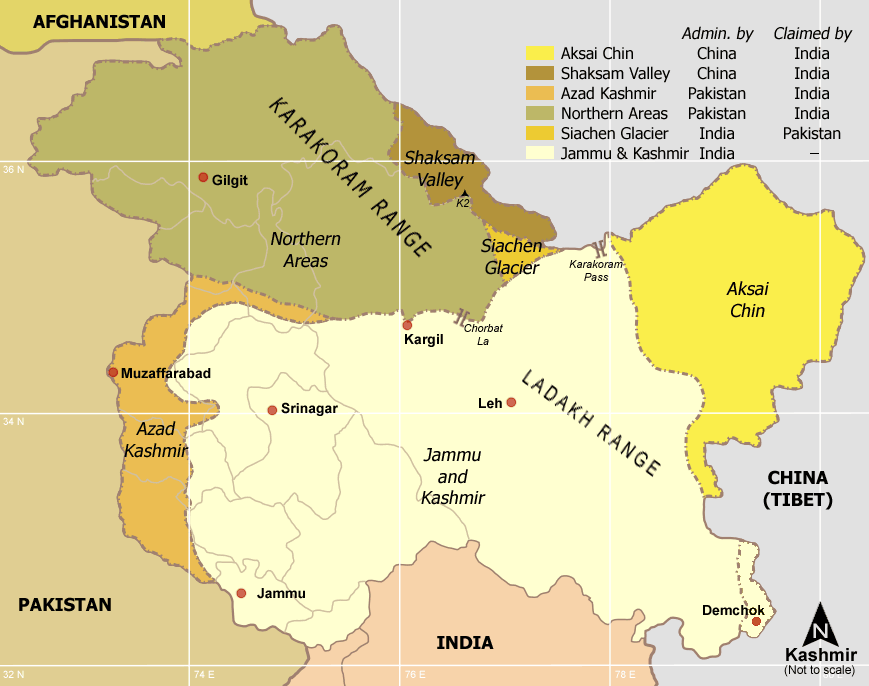

In January 1948, India took the matter to the UN but regretted the decision after the Security Council passed a resolution calling for a referendum to allow the people of Jammu and Kashmir to decide which country they wanted to join. The UN, however, made the referendum conditional on Pakistani forces vacating the region. By the time the UN-mediated ceasefire agreement came into effect in 1949, Pakistan had consolidated control over Gilgit-Baltistan (also known as the Northern Areas) and Azad Kashmir, which are today referred to as ‘Pakistan-administered Kashmir’. The two countries have since fought three wars over Kashmir, and cross-border shelling and aggression have been commonplace.

To add to the confusion, the eastern part of Jammu and Kashmir, known as Aksai Chin, is now under Chinese control, after Beijing seized most of it in the 1962 war with India. (Separately, Pakistan ceded the Shaksgam Valley to China under an agreement signed in 1963.) The remainder of the state has been governed by India since 1948. Nonetheless, the state has witnessed almost constant unrest due to India–Pakistan rivalry, Pakistan’s support for local extremist groups and the Indian government’s fraught relations with key Kashmiri political figures.

Two events in particular unleashed a series of crises that continue to affect Kashmir to this day: the 1987 state elections (which were allegedly rigged by New Delhi and locked in a culture of political unrest) and the spillover of the Afghan jihad into Kashmir (which exacerbated armed conflict in the region). The massacre and mass exodus of Hindu Kashmiri Pandits (the local Hindu community) in late 1989 and early 1990—a result of that spillover—was an especially difficult chapter in the troubled history of the state.

As a result, the Indian government enacted the controversial Armed Forces Special Powers Act in the state in 1990, granting special immunities to the military in the region. Kashmir has always had a heavy Indian military presence, and the army’s actions over the years have frequently been criticised as harsh. There’s been a rise in local militant activity (abetted by Pakistan) in the past decade that successive Indian governments have failed to quell; the execution of local terrorist Afzal Guru in 2013 and further such instances have caused massive unrest and disaffection with New Delhi over the years.

To add to the tensions, Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s Bharatiya Janata Party has promised to repeal articles 370 and 35A (which prevent migration into Kashmir from other states) from the Indian constitution. This has generated heated responses not only from the local Kashmiri parties but also from Pakistan. Overall, the crisis in Kashmir has been a vicious circle of violence, fuelled by Pakistan and crushed by India, that has engulfed the local populace for many decades now.

Ultimately, the conflict over Kashmir is an ideological one. Pakistan was conceptualised by the leaders of the Muslim League in pre-partition India on the assumption that the differences between Muslims and Hindus were irreconcilable, and that the former would never flourish in a Hindu-majority country. Historian Faisal Devji explained Pakistani nationalism as strongly rooted in the idea of rejecting a shared past with the Hindus of the subcontinent.

The absorption of the Muslim-majority state of Kashmir by India is an anathema to Pakistan’s raison d’être, under which a secular India is seen as a threat to the very existence of Pakistan. India’s role in aiding the creation of Bangladesh after 1971 further widened the gulf with Pakistan, which Pakistan expects to avenge by fomenting crises in Kashmir. New Delhi’s economic and conventional military superiority over Islamabad also adds to the latter’s threat perceptions.

Despite steps to increase people-to-people links between India and Pakistan, the Pakistan Army and intelligence service—which exercise a monopoly over the nation’s foreign policy—have ensured that Kashmir remains a boiling issue between the two nations. As C. Christine Fair writes:

Pakistan … has an army that cannot win the wars that it starts, and nuclear weapons that it cannot use, so it must demonstrate that India’s hegemonic goals are not unchallenged. This means that Pakistan must attack India through proxy actors under its nuclear umbrella, just to demonstrate that India has not defeated it or forced it into accepting the status quo.

The easiest setting for any such demonstration is Kashmir—and that means the issue isn’t going to be resolved anytime soon.