Recent developments in the Defence Department’s planning for the land domain illustrate the disjuncture between the high-level policy directions in the 2020 defence strategic update that accurately assess our strategic situation, and the capability investment program in the supporting force structure plan that’s meant to address it. They also highlight the problems that can arise when the industry tail wags the capability dog.

The first was the release on 13 August of Defence’s Sovereign industrial capability priority implementation plan: land combat and protected vehicles and technology upgrades (yes, it’s a mouthful) and the accompanying, more detailed, industry plan. When the government first announced its 10 industry priorities in its 2018 defence industrial capability plan there was already the risk that things would be included merely because they were already being done here. Ending local production and suffering headlines about workforce valleys of death is something no government wants to endure (particularly after the backlash when the government turned off the domestic car industry’s life-support system). But if everything is a priority, then nothing is.

In this, the third of the implementation and industry plans, we can already see the risk being realised. Back in 2018 the industry priority only included armoured vehicles; it now also includes protected vehicles. So, along with tanks, combat reconnaissance vehicles, infantry fighting vehicles and armoured recovery vehicles are Hawkei and Bushmaster protected mobility vehicles, protected trucks and, last but not least, self-propelled howitzers (SPHs). Since the force structure plan suggests that the army will have only armoured and protected vehicles because unprotected vehicles won’t be deployable (pages 76–77), all of its vehicles are now a strategic priority.

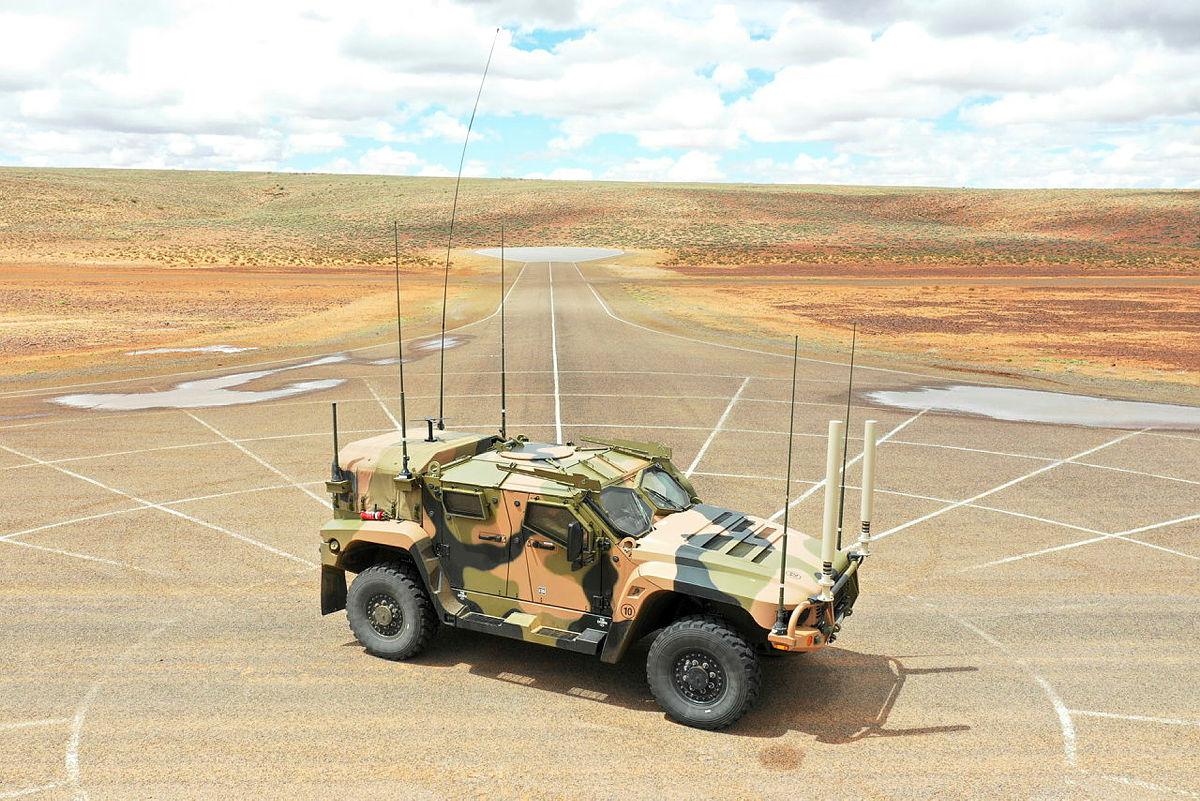

Once you get past the assumption that every army vehicle is a sovereign priority, the industry plan is a solid, thoughtful piece of work. It describes four critical industrial capabilities: protection technologies; integration, networking and communications; vehicles and system upgrades; and sustainment. But nowhere does the plan say that local production or assembly of vehicles is a strategic priority.

With so many strategic priorities, one would expect Defence to avoid paying a premium for things that aren’t high on the list. After all, that’s what a prioritisation framework is all about. Which brings us to the second development.

The government just announced a tender for 30 SPHs and 15 ammunition resupply vehicles with the Korean firm Hanwha. The government first announced it would build howitzers in Geelong during the 2019 election campaign, creating 350 jobs. We have the Department of Finance’s costing for that promise—which assumed a 30% premium for a local build. That’s $245 million out of the total project cost of $1.063 billion. Assuming there are 350 jobs, that’s a subsidy of around $700,000 per job, or around $140,000 per job per year during the build.

But 350 jobs is a big assumption. Queensland ran out the winner in a vicious cage fight with Victoria to land the combat reconnaissance vehicle project and its 1,450 jobs. It turns out, however, that that number was generated by conflating acquisition-phase jobs with sustainment-phase jobs. There are only 700 jobs in the acquisition phase—and Queensland gets only 330 of them anyway. So, Geelong probably shouldn’t count on 350 howitzer jobs. And fewer jobs means an even higher subsidy per job.

But even if it is 350, then it’s taking 350 people to build fewer than 10 vehicles a year—which would make it one of the least efficient projects in history. Which gets us back to the point above—with so many strategic priorities, why are we paying big premiums to inefficiently build things here that we can quickly acquire off the shelf overseas? There’s no evidence that we need to build something here in order to sustain or upgrade it here, or that building here even reduces subsequent sustainment costs meaningfully.

Of course, there’s the issue of whether having SPHs aligns with the strategic update’s telling judgements in the first place. One is that we need new capabilities that ‘hold adversary forces and infrastructure at risk further from Australia, such as longer-range strike weapons, cyber capabilities and area denial systems’. The second is that we can no longer rely on warning time and don’t have time to ‘gradually adjust capabilities’.

Hanwha’s SPHs definitely have greater range than the army’s current towed howitzers, but the additional 10–15 kilometres isn’t going to shape an adversary’s plan to operate against us in the South Pacific. Moreover, injecting a requirement for over $1 billion in acquisition funding into the front end of the force structure plan, which is already oversubscribed, simply displaces the acquisition of capabilities that might give real long-range strike power further into the future.

And if the capability is urgent, setting up a production line to deliver a handful of vehicles each year is the definition of gradual—particularly when Hanwha, having built more than 1,000 SPHs for the South Korean army, could deliver 30 from Korea without breaking a sweat.

Also, what happens to those 350(-ish) jobs once the 30 howitzers are built? As I noted above, governments don’t like announcing job losses. So it’s not surprising that since the initial announcement in early 2019, the SPH program has grown to include a second build phase for more SPHs at $1.5–2.3 billion and a subsequent assurance phase at $2.1–3.2 billion. At a combined $4.5–6.8 billion, it’s quite the turnaround for a capability that couldn’t get even a guernsey in Defence’s 2016 integrated investment plan. If we pick the median point of that price range and assume the same 30% local premium, we’re paying a $1.3 billion premium to sustain those jobs.

The prospect of building off into the distant future to avoid losing the jobs you initially created brings us to the third development, the announcement that the Hawkei protected mobility vehicle light is finally going into full-rate production. With excellent blast protection, the Hawkei will be a valuable capability, assuming its persistent reliability issues have been resolved, so it’s not surprising that the army wants them as quickly as possible. According to the announcement, 50 Hawkeis will be built every month. But that means production ends in mid-2022. So, the 210 jobs in Bendigo and 180 more nationwide that the media release says the project is ‘sustaining’ won’t be sustained for long.

And that’s the challenge in building quantities of traditional manned vehicles and other platforms that match the size of the Australian Defence Force—either you build at the most efficient rate and get the capability into service quickly but face the prospect of jobs ending, as with the Hawkei, or you stretch out production to create a sustainable industrial drumbeat, as with the Hunter-class frigates, which we’re paying $10 billion more to get at a much slower rate.

Defence faces the prospect of sustaining three land vehicle production lines—the Boxer in Queensland, protected vehicles in Bendigo, and SPHs in Geelong. Depending on whether Rheinmetall or Hanwha wins the infantry fighting vehicle competition, that will take care of Queensland or Geelong for some time (at a cost of $18.1–27.1 billion).

But a more strategic approach might have been to require Hanwha to use Thales’ Bendigo facility to assembly its SPH, creating both a centre of excellence for multiple protected vehicle types there and a sustainable workflow. Unfortunately, expedience seems to be trumping strategy.

So, what will happen to the Bendigo production line in 2022? Considering that a previous government spent $221 million on additional Bushmasters that the army didn’t need just to keep the Bendigo facility going until the Hawkei was ready for production, it seems unlikely that this government will close it down. There’s no funding line in the force structure plan to build anything there, but considering the inescapable appeal for governments of announcing local construction programs, it’s a safe bet that Bendigo will keep building something after 2022.

It’d be great if that ‘something’ isn’t a vehicle that the ADF already has in numbers. It would be better if it’s complementary technologies and systems to operate with these manned systems, including the guided weapons that are central to modern warfighting. The ADF will need lots of them in any conceivable future conflict. We’ll look more at those in future posts.