Over several weeks, viral videos have appeared on social media showing individuals flouting public health recommendations and legal requirements and actively attempting to provoke confrontations with staff (or in some cases even police officers) responsible for enforcing those rules. This trend has increased sharply in Australia since the requirement for people to wear face masks in public spaces went into effect in Melbourne.

A range of conspiratorial beliefs are fuelling these incidents. However, the most significant driver is the social affirmation which these videos garner among online conspiracy communities. Conspiracies explain the resistance to wearing a mask, but not the need to film it and share it on social media. People’s desire to film their own refusal to wear masks, and to try to make it more exciting by provoking a confrontation, is a reflection of the ways in which social media interacts with and inspires online conspiracy communities.

Since the beginning of the coronavirus crisis, a swirling galaxy of conspiracy theories has claimed for one reason or another that the virus is not real and is part of a sinister plot which must be resisted at all costs.

This generalised opposition to Covid-19 health measures has crystallised around face masks due in significant part to the intense politicisation of mask-wearing in the United States. President Donald Trump spent months refusing to publicly don a mask and repeatedly undermining public trust in their effectiveness.

Those views have trickled across to Australia in a number of forms, perhaps most prominently in the pro-Trump QAnon conspiracy (which has absolutely exploded since the start of the pandemic) and the ‘sovereign citizen’ conspiracy (which believes that governments can only rule by individual consent and that citizens can rightfully evade laws simply by choosing to do so). These are both off-shoots of conspiracy theories which originated in the US and continue to have substantial ties to the US-based conspiracy communities.

Often it’s not actually clear from the videos which of these conspiracies the person believes, and in some ways it doesn’t matter much. As these weird theories swim around together in the same social-media Petri dishes, they are increasingly cross-propagating and evolving new strains that combine elements of a multitude of different conspiratorial narratives.

One of the most notable features of many videos has been the individual reciting a list of obstructionist questions to the staff member or police officer attempting to enforce the mask rule. In some videos, the person even has a printed list to read from.

This is a tactic that derives directly from the sovereign citizen conspiracy, which encourages its followers to use quasi-legalistic questions and challenges (usually based on extremely misguided interpretations of the law) to undermine government authorities. Several versions of these lists adapted for Melbourne’s mask regulations are being circulated in social media groups.

Some of the questions are straight out of the sovereign citizen playbook, literally. For example, one suggests challenging the definition of ‘driver’ and claiming to be a ‘traveller’ instead to avoid having to show a driver’s licence. This is a sovereign citizen question which is so common in the US that there are articles guiding police on how to handle it.

Unfortunately, this tactic sometimes succeeds purely because the staff member or police officer gives up out of frustration, as we saw in a recent incident in which a Melbourne woman was allowed to pass a check point without answering police questions.

Although it would be a mistake to dismiss these groups as ‘crazies on the internet’ (they’re clearly not just on the internet), it is true that these conspiracy communities are heavily dependent on social media platforms and wouldn’t exist in anything like the same numbers without them. The more such videos there are, the more the dynamics of social media stimulate users to make their video ever more exciting so that it stands out from the rest and gets more likes and comments—including by, for example, deliberately provoking an altercation as we have seen in some of the videos. Even as the videos may be being widely condemned by the mainstream public, in conspiracy Facebook groups they receive hundreds or even thousands of likes and comments of support.

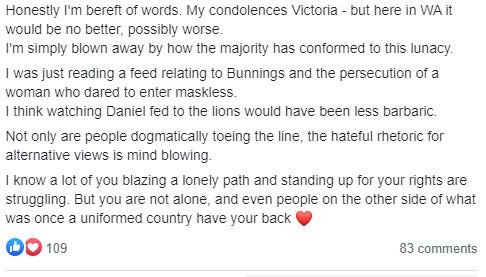

Screenshot of Facebook post about the ‘persecution’ of a woman who refused to wear a mask in Bunnings, comparing her treatment to the biblical tale of Daniel being fed to lions

As an immediate measure, Victorian police and perhaps even retail and hospitality staff should consider adapting some of the advice which is already out there about how to deal with sovereign citizens asking endless obstructionist questions. Now that they have seen some success, we should expect the use of that tactic to continue and to grow, and police, health officers and other frontline workers need to be prepared to respond to it.

In the longer term, social media platforms could consider changing the incentive structures for engagement with conspiracy groups. That doesn’t have to involve removing content (which conspiracy groups would immediately decry as censorship). It could, however, include turning off comments, limiting or blocking likes, or preventing their own algorithms from boosting videos which depict individuals deliberately flouting public health regulations. Taking away the immediate validation which conspiracy theorists are showered with when they post these videos online would remove a lot of the reason for making them in the first place.