Former foreign minister Hayden said, “As Labor came to office in 1972 ‘China’ had become a symbol of a broad judgment of the need for change in many areas”. Stephen FitzGerald recalled of the atmosphere when Whitlam chose him as the first ambassador for Beijing: “I felt part of a movement for social change”. China is often erected as a symbol of a progressive golden age. And occasionally, by Americans, also as a symbol of adverse forces. Such abstraction is a perilous approach to the reality of China.

Former foreign minister Hayden said, “As Labor came to office in 1972 ‘China’ had become a symbol of a broad judgment of the need for change in many areas”. Stephen FitzGerald recalled of the atmosphere when Whitlam chose him as the first ambassador for Beijing: “I felt part of a movement for social change”. China is often erected as a symbol of a progressive golden age. And occasionally, by Americans, also as a symbol of adverse forces. Such abstraction is a perilous approach to the reality of China.

Japan helped pioneer China as a symbol in the 18th century, portraying it as giving non-Western meaning to Japan’s own existence. Russian thinkers in the same century took China as a symbol of virtue on the grounds that the Western Enlightenment esteemed Confucian China and therefore Russian intellectuals should too.

Throughout the 1960s and 1970s and even today, the left in the west has erected China as a symbol for western guilt over imperialism (a stance useful to Beijing). In Japan, the left’s massive (unsuccessful) struggle against the US alliance in 1960 elevated China as the ‘anti-US’, and thus as brother to a Japan smothered by the American embrace. Today, China is popular among American intellectuals as a symbol of the west’s decline. Such declinists embrace the absurd Martin Jacques’ notion (in ‘When China rules the world’) that ‘China’s past is a symbol of the world’s future’.

Today some Australians erect China as a symbol of a dawning Asian Century. I was asked in a radio interview this morning if China is the key to the Asian Century envisaged by PM Gillard. Such a question overlooks the challenges Beijing faces with many tensions, territorial disputes and contradictions with other countries in Asia (more than it has with Europe or the US). Beijing would have a tough time presiding over Asia and its history in Asia should give pause to folk who welcome China as replacement for the US in the Asia–Pacific. China was intermittently an imperial power in East Asia, not least in the climactic Qing Dynasty.

During the Marshall Mission to China in the 1940s which sought to reconcile Mao Zedong and Chiang Kai-shek, General Marshall’s chief aide wrote home to his wife from Nanjing: “It seems that for time beyond man’s recollection, China has been the desire and design of people outside China. What that has to do with China, as China is today, is another question, but the fact remains that many nations have their eye on this place out here”. In truth, China isn’t a symbol of anything; it’s just multifaceted China. It’s hazardous to essentialise China into a symbol of guilt, hope or fear.

If we’re to choose a context for China’s rise, the best might be ‘modernising China is a major ingredient in globalisation’. The coincidence of enlightened post-Mao Chinese development policies and growing international economic interdependence is of great historical importance to the Asia Pacific. This actual China is distant from the ‘China’s past’ that Jacques calls the world’s future. Refreshingly, China’s current renaissance draws on ideas and resources from around the globe and across the political spectrum. China’s new civilisation will be one ingredient in globalised evolution, but not its heart. China‘s urban youth by no means focus on China’s past; why should Australian youth do so? The 21st century will not be China’s; it will not be any one country’s. That is, unless globalisation stalls, technology goes to sleep, and young people cease to trend cosmopolitan.

This post is excerpted from the author’s ASPI Strategy report ‘Facing the Dragon: China policy in a new era‘.

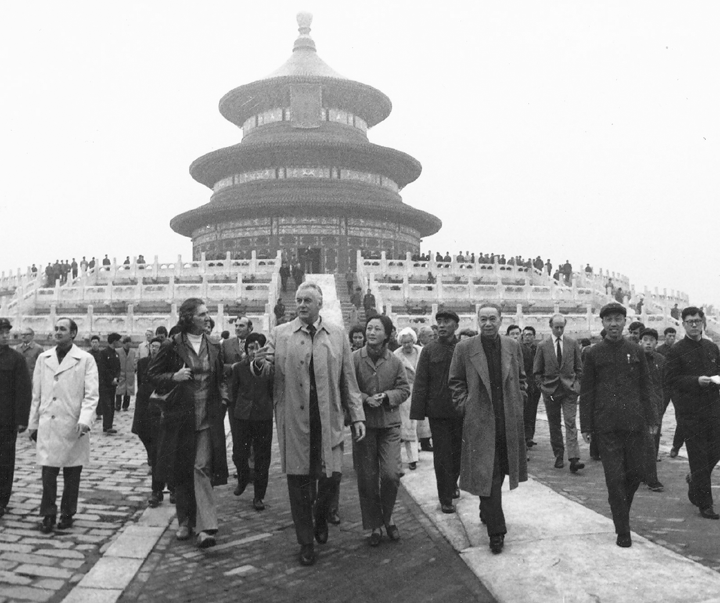

Ross Terrill of Harvard’s Centre for Chinese Studies is a visiting international senior fellow at ASPI. Image courtesy of DFAT.